by Natalie Hoefer

In the 1950s, Norbert Krapf was sexually abused – along with scores of other boys – by a priest of the Diocese of Evansville, Ind., who was loved and respected by the community.

In the 1950s, Norbert Krapf was sexually abused – along with scores of other boys – by a priest of the Diocese of Evansville, Ind., who was loved and respected by the community.

After five decades of silence, Krapf – a retired professor, author and award-winning former Indiana Poet Laureate – confronted the monster of his past both by outing the then-deceased priest to the bishop and, in 2012, publishing a book of poems called “Catholic Boy Blues” to help himself and other victims heal.

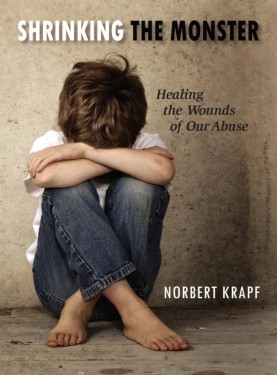

This year, Krapf published “Shrinking the Monster: Healing the Wounds of Our Abuse” (Munhall, Pennsylvania: In Extenso Press, 2016, pp. 236, $14.95). In Krapf’s own words, the book is a “prose memoir about the experience of writing those poems, with an emphasis on the process of my recovery from the abuse.” That experience, as outlined in the book, was a journey of pain, struggles, victories and healing.

Why write on such a dark, painful topic that many would, as he admits, rather not read about?

The answer is twofold. First, as Krapf reiterates at several points, the book is to help other victims of child abuse heal, and to further his own healing. But that doesn’t mean the book is only for victims.

Rather, it serves the additional purpose of raising awareness and prevention of the lifelong pain and damage caused by child abuse, wounds that Krapf reveals can be managed but never fully heal, wounds that can be reopened at any time.

The book has a “’round the kitchen table” feel, like that of a friend sharing his heart with the reader over coffee in cozy quarters. That feel comes from the level of honesty and openness with which Krapf writes.

In the spirit of revealing the depth of the pain and the balm of healing from sexual abuse, he takes the reader through his eight-year journey from the point of knowing his story must be told, through the pain of facing “the monster” of his past after 50 years of silence, to the struggles and healing process of writing and publishing “Catholic Boy Blues,” which is helpful but not necessary to have read to follow the journey of “Shrinking the Monster.”

Through an accessible storytelling style, several processes come to light in this memoir.

First are the actual steps Krapf took in making his abuse known to the bishop of Evansville. Through several chapters, interwoven with the struggles abusers face in confronting their past, can be found the wheels that were set in motion at the ecclesial level once the sexual abuse by the priest was officially confirmed.

Krapf acknowledges gratitude for efforts made from the local level to Pope Francis in helping victims of clergy sex abuse and addressing the crime of such “trusted shepherds,” while at the same time expressing concern that more concrete actions need to be taken.

Second is the process of how Krapf wrote “Catholic Boy Blues” as a means of his own healing, and to speak for the voices of all children who have suffered abuse at the hands of an authority figure. He shares how, once the vein of pain was tapped, the poetry exploded in the surprising form of various voices – the boy who was hurt, the man who carried the child within him, a helpful mentor named Mr. Blues and eventually the voice of the priest himself.

The reader also learns of the process of publishing the poetry book – the struggles, the re-opening of wounds and the friends who brought healing to the journey, including his wife, Katherine; his former pastor, Father Michael O’Mara and Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin, the archbishop of Indianapolis who was installed Jan. 6 as the archbishop of Newark, N.J.

For readers who are victims of child abuse, look for advice throughout the book on how to shrink your own monster. Krapf shares words of his counselor that proved life-changing for him, such as, “If you remain angry at your abuser, it means he still controls you”; “If you keep the monster silent inside of you, it could grow bigger and bigger until it starts to eat you alive”; and “Every time survivors tell anyone we trust something about our abuse, we heal just a little.”

He also shares what he has learned about forgiveness – a step that takes a long time for victims of child abuse, he admits.