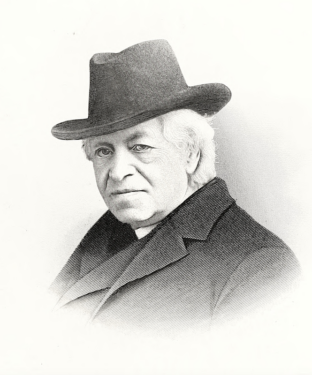

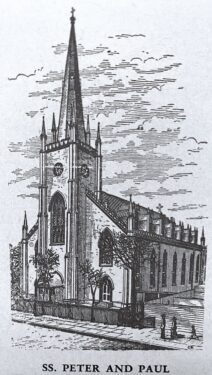

WILLIAMSBURG — Father Sylvester Malone, pastor of Ss. Peter and Paul Parish from 1844 to 1895, knew first-hand the vitriol spewed at his fellow Irish immigrants in the 1850s. As the priest strolled the streets of Williamsburg, then a stand-alone city, volunteer firefighters often peppered him with insults and curses.

By 1854, the U.S. was still 22 years away from its Centennial Birthday. Still, the firefighters shared a sense of nationalism, having been born in the United States.

They also fomented anti-immigrant animosities that sparked rioting after election day, Nov. 8, 1854, in Williamsburg. Father Malone was out of the country, but parishioners told him how, on the evening of Nov. 9, a mob attacked his beloved church, the first-ever designed by famed architect Patrick Keely.

Years later, the pastor wrote about how Williamsburg Mayor William Wall repeatedly tried to disperse the mob. But then, around midnight, there was a cry, “To the church! Let’s burn it!”

Here’s a look at how the anti-Catholic sentiment arrived in Brooklyn, and how the actions of Father Malone and Wall helped preserve the faith in the borough for generations to come.

RELATED: NYPD’s ‘Italian Sherlock Holmes’ Honored With Headstone Nearly a Century Later

Goodwill Ebbed

Christians have faced violent, systemic persecution since the reign of Emperor Nero of Rome, some 50 years after the crucifixion of Jesus. The violence continued on and off until Emperor Constantine the Great decriminalized the faith — and eventually joined it — in the 4th century.

Christians, however, would split in 1517, when the Reformation began in Germany, forming two camps: the Roman Catholic Church and Protestantism. Anti-Catholic sentiments subsequently prevailed in European nations and, by extension, their colonies in North America. Exceptions were France and Spain, but not England.

Maryland was the only British colony in the “New World” where English Catholics were allowed to settle. But anti-Catholicism eased somewhat after the American Revolution.

President George Washington, working from the temporary capital in New York City, struck a conciliatory tone by writing to Catholics. He thanked them for their service in the War for Independence.

That goodwill, however, ebbed in the next century when native-born residents of New York City started to resent the large numbers of immigrants arriving from famine-ravaged Ireland and elsewhere.

These “nativists” resented how the newcomers competed for jobs, housing, and eventually, political power. In addition, criticizing the immigrants’ Catholic faith grew, spurred by suspicions of papal influence.

But economics also fueled the animosity, said Patrick Hayes, the archivist for the Baltimore Province of the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (Redemptorists) in Philadelphia.

Hayes described how, in 1850, Archbishop John Hughes of New York — himself an immigrant from County Tyrone, Ireland — joined efforts to develop the Emigrant Savings Bank.

Hayes, who formerly taught theology at Fordham University and St. John’s University, said this new bank brought economic clout to the immigrants.

“Suddenly, they’re making loans and causing a shift in affluence,” said Hayes, who is also a member of the American Catholic Historical Association.

Thus, Hayes said, the stereotype that immigrants were poverty-stricken drunkards no longer held. Meanwhile, immigrants also worked for less than the going wages for native-born laborers, he added.

“If suddenly you have an Irish Catholic immigrant vying for your job or your children’s jobs, you get very protective,” Hayes said.

RELATED: Father Peter Purpura Sworn in as FDNY Chaplain; Aims to Continue Legacy of Msgr. Delendick

Bill the Butcher

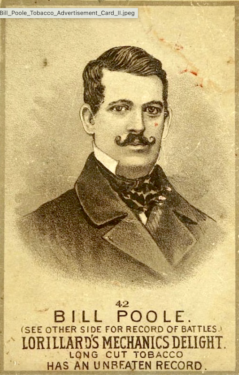

Into this volatile mix emerged William Poole, a butcher by trade, but also a gambler and frequent pugilist known to fight dirty. He especially liked beating on Irish Catholics.

Nicknamed “Bill the Butcher,” Poole was an outspoken leader of the “Know Nothing” nativism that grew into a nationwide movement. Poole recruited a cadre of like-minded brawlers — one of several street gangs operating in Manhattan’s Five Points neighborhood. His crew was called the Bowery Boys. In 1856, Millard Fillmore was elected president of the U.S., running on the party line.

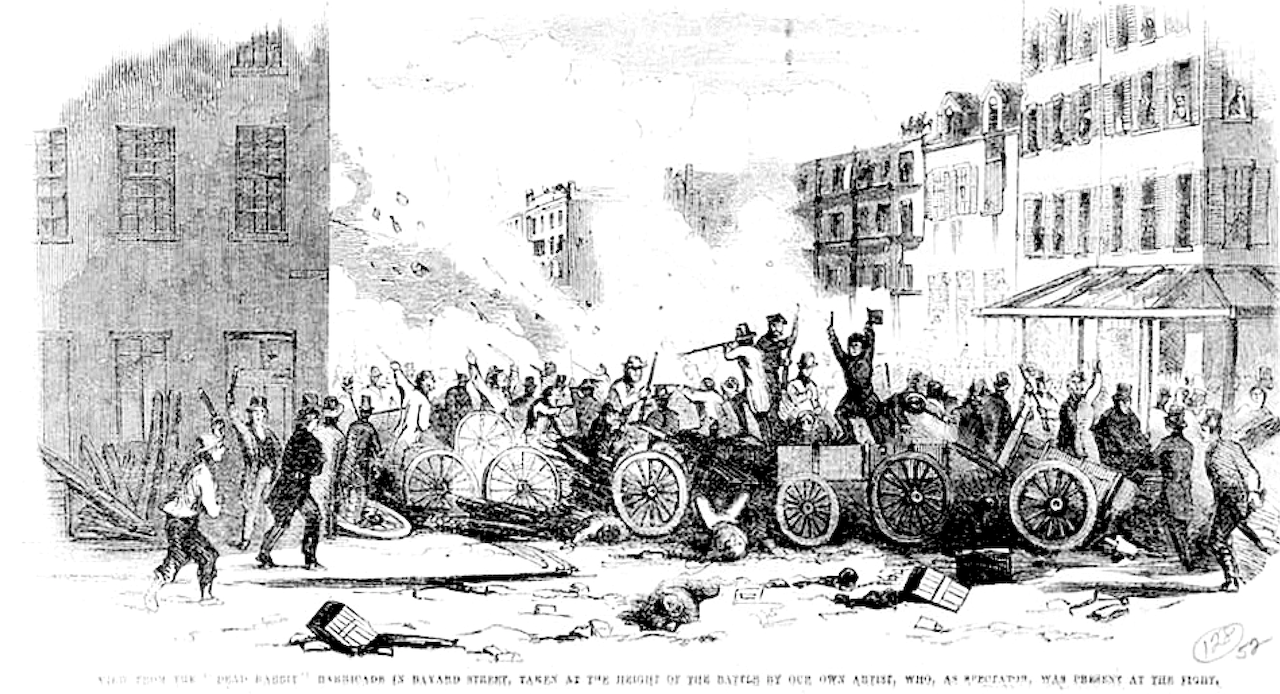

Irish Catholics countered with their own gangs, like the Dead Rabbits, who fought the Bowery Boys in street brawls that would sometimes become deadly.

The trouble spread to Long Island on Nov. 9, a day after the contentious 1854 election.

According to Father Malone, hooligans from the “Bill Poole element of New York City” came to Williamsburg to stir post-election rancor. Father Malone wrote that at the church, “a cry was raised for straw and matches to fire the edifice.”

But at that moment, the aforementioned mayor, William Wall, reemerged.

Over His Dead Body

According to Father Malone, the mayor proclaimed that “no one should enter that church except over his dead body.”

“The mob dispersed, passing up South Third Street, hooting and jeering at the pastoral residence as they went by,” Father Malone wrote.

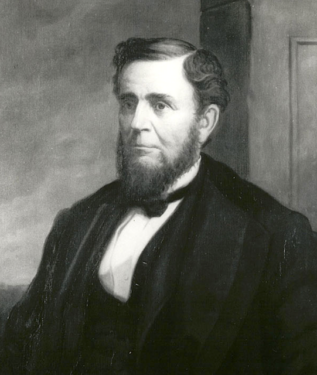

Wall, a ropemaker by trade, also represented a Long Island district in the U.S. Congress during the Civil War. The mayor remained friends with Father Malone. He wasn’t Catholic, but Episcopalian, according to his obituary in 1872.

Nativism in New York City started to decline after the 1854 election, Hayes said.

Subsequently, the Catholic Faith’s growth — which began some 20 years earlier with the ministries of Father Felix Varela — took a major leap forward, he said.

“So,” he added, “between 1840 and 1870, between the Irish and the Germans, Catholics became the principal religious group in the United States.”

Italian Catholics and other groups contributed to the population growth, Hayes said.

“It’s one of the great things about the City,” he added. “You get all these different kinds of people with different languages and ethnic backgrounds, but their Catholicism unites them all.”