BEDFORD-STUYVESANT — The wail of sirens and the steady grind of helicopters aloft on May 12 clued Father Alonzo Cox that late-night violence had erupted yet again.

It was not until morning that he learned the details. Police said an officer traded gunfire with a known gang member sought in another shooting moments earlier. One cop and the suspect were wounded, but survived; a man in the earlier shooting did not.

“That was literally blocks down from my rectory,” said Father Cox, pastor of St. Martin de Porres Parish in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood on the north side of Brooklyn.

“I was up late,” he said the next day. “And I heard all these cop cars and the helicopters. And I’m like, ‘Something’s going on …’ The helicopters were still hovering at 9 o’clock this morning. I heard the cop got shot three times, and thank God for his bulletproof vest.”

Father Cox, also the coordinator of the African American Apostolate in the Diocese of Brooklyn, said the latest hike in gun violence citywide is “hitting close to home.”

“We’ve discussed this as a parish,” he said. “And the one thing that comes up is, ‘What are we doing about gun violence?’”

Two nights earlier, and four miles east of Bed-Stuy, Father Ed Mason had a similar experience. The administrator of Mary, Mother of the Church Parish on Linwood Street in East New York was relaxing in the rectory, watching a movie.

“I heard sirens down the block,” Father Mason recalled, “but I didn’t realize they were stopping there. I kept watching the movie, but down the block, a kid got shot. Killed. They’re saying it was gang-related.”

According to reports, Shaheem Bascom, 18, who lived in Bed-Stuy, came to East New York to meet a girl at the corner of Linwood Street and Hegeman Avenue.

His family said the aspiring rapper was not in a gang, but gang members still targeted him.

Father Mason’s parish is also on Linwood, at the other end of the block. A few weeks before the shooting, he conducted a tour at the same spot to show how it is one of several go-to locations in the neighborhood for illegal dumping.

He said gun violence is “a part of life here.”

“It hurts every single time,” he added, “but it is not shocking. The outrage gets muted because it happens so often.”

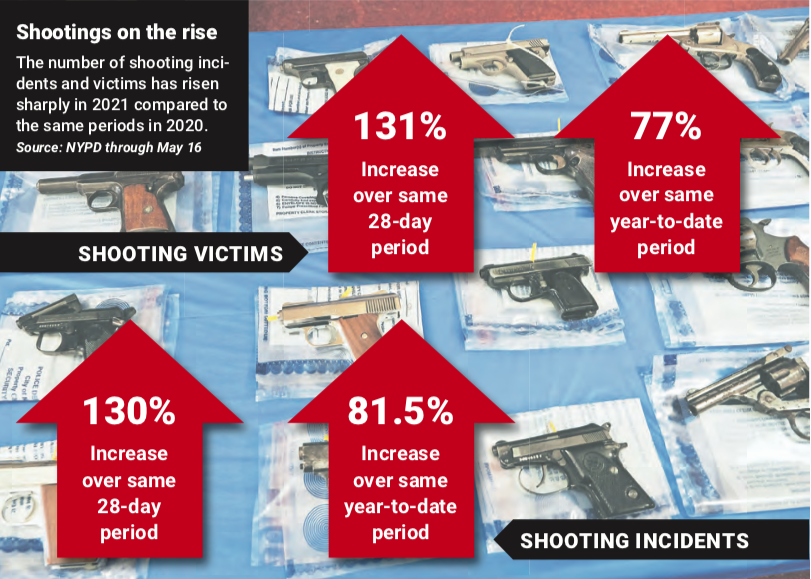

New York Police Department data shows how gun violence escalated over the past year. From January 1 through May 16, 552 people were shot citywide, a 78.6 percent increase over the 309 shooting victims through the same period in 2020.

Last month was especially violent, with 149 shooting incidents. That is a 166 percent boost over April of 2020, which produced 56 shootings, NYPD data shows.

‘Known to the police’

Police say the May 12 incident began at 11 p.m. near the intersection of Madison Street and Broadway Avenue. They said a gunman ran up to a white sports utility vehicle with three occupants; he opened fire, killing one.

Responding officers stopped the suspect and shot it out with him about four blocks away near Saratoga Park.

The wounded officer, 28, and the alleged shooter, 26, were taken to Kings County Hospital. There, Police Commissioner Dermot Shea and Mayor Bill de Blasio held a press conference.

Shea said the three men in the SUV and their attacker are all “known to the police” as gang members with pending cases from previous arrests on gun-related charges.

“They’ve been arrested in the recent past,” added Chief of Detectives James Essig. “They have future court dates after the summer.”

Essig said there were multiple recent shootings in the area.

“When we see this, it’s always gang members involved,” he said. “We know which gangs they are in. We know who they dispute with. You constantly see the back and forth, and that’s why we have officers deployed in that area.”

A most basic human need

The recent violence reminds Father Mason of the 1990s during the crack cocaine epidemic. Back then, most funerals were for young men in their early 20s, he said.

Crime rates started to fall in the final months of David Dinkins’ last term as New York City mayor, Father Mason said. That trend accelerated with the next mayor, Rudy Giuliani.

“It was a tremendous transformation,” Father Mason said.

Still, he noted, gang activity never completely subsided, a consequence of broken families and communities unable to meet one of the most basic human needs — a sense of belonging.

Father Cox and Father Mason said they believe the pandemic made things worse.

“There has been so much violence going on, including the shootings in Times Square this past weekend, and in the subways, the attacks there,” Father Cox said on May 13. “Everybody’s been stuck in their houses, and nobody wants to be stuck in one place for a long period of time.”

“People are troubled,” added Father Mason. “We have an uptick in racial tension and an uptick in socioeconomic disparity. But, yeah, I think the pandemic knocked people off-kilter — off their center of gravity. There’s a great amount of instability in families and in people’s personal lives.

“Well, I think these are all factors that increase the violence.”

Achieving the lower crime rates of the past two decades “will take a lot of work,” Father Mason said.

“The key,” he added, “is knowing what to do and how to do it. That’s where we come in — organizing people. We don’t complain. We don’t have protests. We have strategizing sessions, and we get solutions.”

To be safe

Father Dwayne Davis, pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas Church in Brooklyn’s Flatlands neighborhood, said the problem won’t be solved with one solution, or by a single group.

“In order to eradicate it, I think everybody has to come together for it — the elected officials and churches, families and neighborhoods,” he said. “I think the Church definitely could play a role in the helpful dialogue and could be a great mediator.

“Because it is our sons and daughters who are being killed,” he stressed. “They’re God’s children. We’re all God’s children. But what affects one affects each other, especially if you look at the African proverb, ‘It takes a village.’ ”

During the past year, more handguns flowed into New York City, according to police, despite the city having some of the most restrictive gun laws in the country.

“I get the fact that a person has a right to bear arms,” Father Cox said. “But there are so many guns on the street, it just boggles my mind.

“I know that the gun buyback programs that I had heard of have been extremely successful, so I think that’s one idea.”

One NYPD buyback event, “Cash/iPads for Guns,” was held May 22 at CAMBA’s Cornerstone Center at Howard Houses, 90 Watkins St., in Brooklyn.

Father Cox said the community working with police is crucial. He noted, however, that the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody a year ago did much to undo goodwill with law enforcement nationwide.

Because of that, Father Cox said, “Many of my young people don’t trust the police and I can’t blame them. But I’m reminded that not every law enforcement officer is looking to lock up a black kid. I don’t believe they are the enemy.”

“I think for us, we need to come together with police to be able to have a healthy dialog, a conversation,” he added, “not forgetting about the past, but building on what we all can do to be safe.”