WINDSOR TERRACE — New York City museums and other cultural institutions began operating once again on Aug. 24, under New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Phase 4 reopening plan. Since then, many museums have curtailed occupancy to a 25-percent capacity, issued timed-entry reservations online with staggered, in-person entry times, controlled foot traffic flow, and limited days and hours of operation.

“This pandemic is far from over, but we’ve determined that institutions can reopen if they adhere to strict state guidelines and take every precaution to keep visitors safe, and I look forward to seeing them inspire New Yorkers once again,” Gov. Cuomo said on Aug. 14.

Readjusting Exhibition Timelines

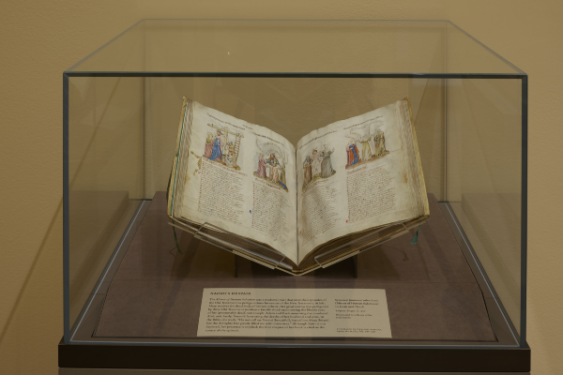

The Morgan Library & Museum reopened to the public on September 5. Home to rare books, manuscripts, drawings, and prints collected by Pierpont Morgan and his son, the Morgan also features a handful of exhibitions.

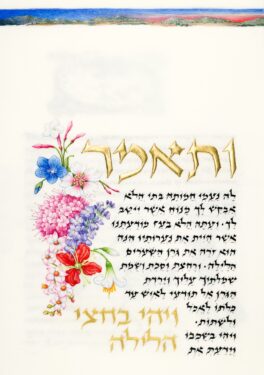

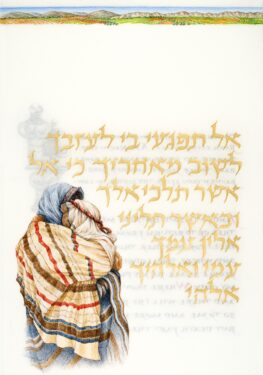

“The Book of Ruth: Medieval to Modern” exhibition, for example, opened on Feb. 14 and was inspired by the 2018 gift by Joanna S. Rose of the Joanna S. Rose Illuminated Book of Ruth to the Morgan Museum. The 18-foot-long, accordion-fold vellum manuscript was designed and illuminated by New York artist Barbara Wolff, who worked on the project from 2015 to 2017. The complete biblical text of the Book of Ruth is written in Hebrew on one side and in English on the other by calligrapher Izzy Pludwinski. The Hebrew side takes inspiration from biblical responsa (written replies by rabbis or Talmudic scholars to inquiries on some matter of Jewish law), commentary, and folklore, featuring 20 colored illustrations and a continuous landscape, with accents and lettering in silver, gold, and platinum. The English side has 40 pen drawings that depict objects, plants, and animals that the Book of Ruth’s early Iron Age people would have known.

“Wolff is inspired by medieval techniques: guilding, painting on vellum, writing by hand, and using precious metals. The iconography of what she has to say and wants to paint is a rather different kind of approach from that of the Middle Ages,” explained Roger Wieck, the Melvin R. Seiden Curator and Department Head of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, who put the show together. “I call it an ‘archaeological gloss’ on the text.”

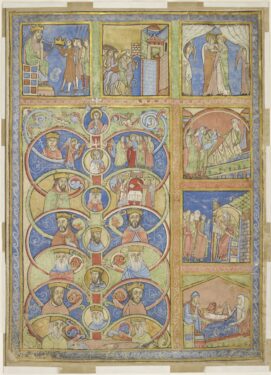

The Rose Book of Ruth, according to Weick, helped fill a hole in the Morgan holdings as the Morgans themselves did not collect Hebrew manuscripts. It was complemented by 12 manuscripts that were already in The Morgan’s holdings, which showed various illustrations from the story of Ruth during the Middle Ages — including 16 scenes found in the Morgan’s famous Crusader Bible.

“When we get donations of modern art from the 20th and 21st centuries, they’ll go to the appropriate departments,” Wieck said. “They usually don’t inspire juxtaposition with medieval manuscripts in the way Wolff’s work naturally does.”

Though the exhibition will close on Oct. 4, it was supposed to leave June 14. Like many others in museums worldwide, the pieces were unseen for a majority of its scheduled stay due to the pandemic. So, “The Book of Ruth” remained open another month to have a “post-COVID-19 show.”

“We were able to stretch it because of the pandemic. But, also because of the pandemic, we have to close it since we’re opening a new fall season,” Weick told The Tablet. “Though the lights were obviously off [during the closure], manuscripts are not supposed to be open for that length of time. It stresses their bindings … and they need to be closed and put back into the vault to rest. So it’s also for that reason that we couldn’t have it up for a longer time.”

Reopening an Iconic Institution

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which celebrates its 150th anniversary this year, had to eliminate 20 percent of its staff through two rounds of furloughs, layoffs, and early retirement offers, and they were forced to close their showcase for Modern and Contemporary Art at the Met Breuer in July. It estimates $150 million in lost revenue from the pandemic through June 2021.

According to its Fiscal Year 2019 records, The Met welcomed more than 7 million visitors to its three locations — The Met Fifth Avenue, The Met Cloisters, and The Met Breuer — for the third year in the row. International tourists accounted for 28 percent of the museum’s visitors, locals from the City’s five boroughs made up 35 percent of the overall total, and 16 percent were from New York’s tri-state area.

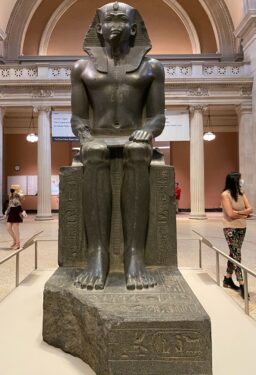

The Met Fifth Avenue saw as many as 40,000 visitors on any given Saturday, pre-pandemic. Now, it may see as many as 10,000 visitors in a single day under the 25-percent occupancy limit. Its Great Hall, with statues of Athena Parthenos and Pharaoh Amenemhat II on either side upon the entrance inside, is essentially the gateway to exploring more than 2 million square feet of gallery space.

One of the exhibitions currently on view is “Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance.” It features a loan, plus 62 masterpieces of 16th-century northern European art from The Met collection. According to Relative Values’ curator Elizabeth Cleland, many of the decorative objects, made of different mediums like stained glass and carved wood, had never been on display before. The installation revolves around questions of historical worth and contextualizes relative value systems in the Renaissance era.

First shown in 2017, it was scheduled to be on display until the spring of 2019. But the decision to extend it was made in part due to the positive feedback it received from visitors, families, and school children who came on field trips before the pandemic hit. The other contributing factor was the museum’s unexpected closure this year.

“We were intending to take it down, but then COVID-19 struck,” Cleland told The Tablet. “But we decided [in March] that we would keep it up for another year again.”

The Saint Veronica tapestry made around 1525 is the “central piece, the hinge for the whole show,” according to Cleland. She noted the tapestry would have been very expensive to make and purchase at the time, being worth 52 cows in terms of 16th-century market pricing.

“There’s this post-medieval idea going into the Renaissance where really gorgeous and highly valued raw materials — in their transformation through virtuosity and craftsmanship — take on the ability to encourage the viewer to reach a greater spiritual place. That includes the Saint Veronica tapestry, the 1608 gold chalice from the Speyer Cathedral, and the pilgrims’ badges …. which are the cheapest things in the whole show, in terms of raw materials,” Cleland explained.

“But the badges are the most valuable items there, in terms of their devotional strength and power. If you were wearing a saint’s badge, you were protected from bad things and could travel under this protective shield, so to say.”

Cleland, who continues to work remotely from home like many other curators, says she’s excited that The Met is back up and running.

“The treat for us is we are allowed to go in with the general public to visit the gallery,” she said. “Sometimes, I do that to get a little dose of normalcy.”

To shake things up, the installation — which has already had two different iterations since 2017 — will have some of its objects swapped out in October.

Deaccessioning Artwork

Museums in the City and across the country have also had to reevaluate their collections and finances as the pandemic continues.

The Brooklyn Museum will be deaccessioning — or putting up for public auction — 12 pieces from its 16,000+ pieces at Christie’s on Oct. 15 to raise money for collection maintenance and create a collection care fund. Some of those soon-to-auctioned-off works include paintings by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) previously stated that proceeds from auctions could only be used to acquire more work. However, in April, AAMD announced that museums could “use the proceeds from deaccessioned works of art to support the direct care of the museum’s collection” through April 10, 2022. Money from deaccessioned art cannot be used for general operating expenses. In the Brooklyn Museum’s case, money received from the auction will go towards direct care of the collection, and a percentage of employees’ salaries.

Other museums planning deaccessioning include the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse. For instance, the Everson will sell Jackson Pollock’s “Red Composition (Painting 1946)” at Christie’s on Oct. 6. The Pollock painting, donated to the museum in 1991 by Dorothy and Marshall M. Reisman, is estimated to be worth between $12 and $18 million.

“Proceeds realized from the sale will be used to establish a fund for acquiring works created by artists of color, women artists, and other under-represented contemporary and mid-career artists,” the Everson said in a statement on Sept. 3. “Funds realized will also be used for the direct care of the Museum’s collection of more than 10,000 pieces, in keeping with guidelines established by the American Alliance of Museums and the Regents of the State of New York.”

New acquisitions made possible by the sale are slated to begin next year and will be announced publicly with credit to the Dorothy and Marshall M. Reisman Fund.