I think it was back in the 1960s, or the early ’70s, that I became very interested in the nature of life commitments, the kind of commitments that people make when being baptized, when marrying, when being ordained, or when taking religious vows. Whenever it was, several couples I knew were living together, friends were leaving the priesthood and other men were leaving religious communities of brothers, and women were leaving the convent. This was a completely new phenomenon in my experience.

In philosophy classes, I started to raise questions about life commitments: What are they? Are they possible? When is a person free enough and sufficiently mature to make one? Reflecting on life commitments raised all sorts of other philosophical questions, especially questions about freedom. In all my reading and reflecting about life commitments, the philosopher whose insight into the human mystery helped me most was Gabriel Marcel.

Another philosopher who helped me as I tried to reflect seriously on life commitments was the famous atheist, Friedrich Nietzsche. He believed that not every human being was capable of making a life commitment. I confess that as a young priest, I thought that any and every human being could make a lifetime commitment. The increase in annulments granted by the Catholic Church in the last 50 years is evidence that more is required for a marriage to be valid than a person’s ability to say the vows.

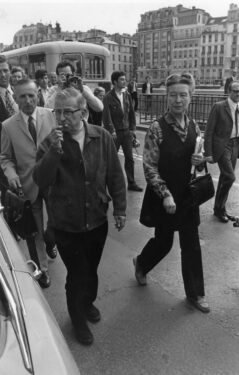

The philosopher I read who was most opposed to life commitments was the atheistic existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre. He believed that in principle life commitments, even if they were possible, should be avoided because the promises that are involved in making a life commitment work against a person’s freedom. For example, Sartre claimed that marriage vows were immoral. The vow to promise to love someone for life destroyed the freedom that should be part of the act of loving. Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir lived together for many

years but never married. At the time that I was reading Sartre’s views, I met many people who never heard of Sartre but had the same view of the marriage contract that Sartre had.

Marcel thought that those who claimed that a life commitment was impossible had missed something of the mystery of the human person. He thought that some claimed that life commitments should not be made because they stressed that the future was unknowable. Marcel thought they were incorrectly thinking of the future as though it were like the weather, something that happened to a person over which the person had no control. Marcel believed that to some extent, not completely, but to some extent, we create our future by the choices we make.

My view of freedom and the future is that to some extent we are the persons we have chosen to be. Granted that many realities influence us, such as our parents, our siblings, the neighborhood in which we grew up, the schools we attended, the films and television that we viewed, and other realities. However, my opinion, and of course I cannot prove this, is the person writing this column is the person he has chosen and is choosing

to be. I would say the same about every person reading this column. In my view, the bottom line and the two most powerful realities in shaping us and forming us are God and our freedom.

Marcel did not explain life commitment completely. Perhaps no one can. One problem with Marcel’s view is that he claimed that a certain level of maturity was necessary for a person to be able to make a life commitment but he also claimed that such a level of maturity could only be achieved by making a life commitment. Which comes first, the maturity or the commitment?

Perhaps the best way of approaching the mystery of life commitments is by reflecting on God’s commitment to us. This is a commitment that will never be broken. I believe that because of God’s permanent commitment to us we can make a life commitment to God. There are some very dramatic actions such as religious vows or marriage vows that express that commitment. However, the commitment is repeated and renewed every time we bless ourselves, every time we pray even a prayer of petition, every time we celebrate a Eucharist. We will not know whether we have been faithful to our life commitment until we reach the end of our lives and

stand before the presence of God. But even before we die, I think we can see that a successful life commitment to God has the greatest possibility of making us sons and daughters of our heavenly Father, brothers, and sisters of Christ and channels of the Holy Spirit.

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, every Tuesday at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.