Every spring semester at St. John’s University I teach an elective philosophy course entitled “The Problem of God.” I don’t like the title, which I inherited, but teaching the course has been a wonderful educational experience for me. I shaped the course so that I might study and teach what some of the most influential minds have thought and taught about God. The content of the course has moved me and the students to probe more deeply into the mystery of God and the mystery of the human person.

Insights into one of these two mysteries can lead to insights into the other; erroneous judgments about one of these mysteries can lead to erroneous judgments about the other. During the course, I try to help students see that how we think and talk about God can influence how we think and talk about ourselves, and how we think and talk about ourselves can influence how we think and talk about God.

About a third of the course is spent reading and discussing some of the most influential atheistic thinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth century. Though I believe in God, I have found that reading the influential atheists has convinced me that the idea of God that they were attacking should have been attacked.

The idea of God they were attacking was in some way anti-human. Instead of a God whose love calls us to become freer, the idea of God that atheists attacked prevented persons from growing and developing. I see now why many of the atheists were actually antitheists, militant in their rejection of the ideas about God that they knew. Indirectly atheists may have helped believers to correct erroneous views of God.

In his “Building the Human” (New York: Herder and Herder, 1968, pp. 192) Robert Johann, after celebrating God’s presence in our lives, points out that a culture can either foster our awareness of God’s presence or, unfortunately, do the opposite.

“Needless to say, God is all this for us only when the cultural embodiment of His presence allowing Him to be for us. Religion, as a cultural achievement, stands as much under God’s judgment, and is continually in need of reform as anything else. That past religious traditions have not infrequently obscured God’s liberating significance goes without saying. Nor is this the place for a discussion of how they might be revived. The point is that if God is the One who frees man to build his world and become himself in the process, then there are not a few, still standing, religious idols that must be tumbled to make room for Him. And if this is the case, then present-day atheism is not without positive religious import. By iconoclastically espousing the cause of human freedom and creativity, it has awakened the religious conscience from complacency to an ashamed awareness of its shortcomings. Though not itself the full answer to man’s plight nor a wholly reliable herald of salvation, nevertheless, by concentrating on the meaning of man it has thrown no little light on the meaning of God.” (p. 188)

When I was a college seminarian, someone, perhaps a professor or a fellow seminarian or some other friend, impressed on me the importance of accepting truth wherever I might find it. I think openness to truth wherever it might be is one of the great character traits of St. Thomas Aquinas. I hope that through the many years I have been teaching philosophy, I have done that and in some way instilled that openness to truth in those I have taught. My desire to accept truth wherever I find it has led me to some heroes who might seem like strange intellectual companions for a priest to have.

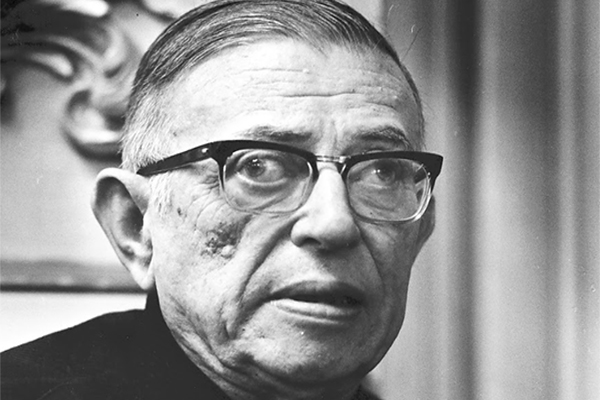

I think of the playwright Eugene O’Neil, a non-practicing Catholic, whom I think of as America’s greatest dramatist. Or author-director, Ingmar Bergman, an agnostic whom I consider the greatest talent in the history of cinema. In philosophy, I think of how much I have learned from the atheist Jean-Paul Sartre.

To dialogue with those whose vision of life is almost totally different than the Christian view can be dangerous. I tell students at St. John’s University that if their approach to philosophy is reducible to how to get an “A” in a course, then there will be little chance that philosophy will upset them, disturb their consciences or cause them to struggle with the most important questions about human existence.

Taking philosophy seriously can be dangerous. Is studying philosophy worth the risk? I can only tell the students of my own experience in studying philosophy. Studying and teaching philosophy has been one of the great blessings in my life.

Father Lauder is a philosophy professor at St. John’s University, Jamaica. He presents two 15-minute talks from his lecture series on the Catholic Novel, every Tuesday at 9 p.m. on NET-TV.