St. John Paul II was a churchman known for his public activism and as a major world figure during the latter part of the last century.

As a priest, bishop and cardinal in communist-ruled Poland, he learned how to deal with an authoritarian atheist regime, helping to keep faith alive and flourishing in the historically Catholic country.

As pope, he was instrumental in the fall of the Soviet empire and the end of the cold war, chipping away at the Iron Curtain with his constant calls for religious liberty and respect for human rights.

Hot-Button Issues

As head of the Catholic Church, St. John Paul updated Catholic social teachings, especially concerning such politically hot-button issues as protecting the environment, economic and political globalization and support for democracy as a form of government.

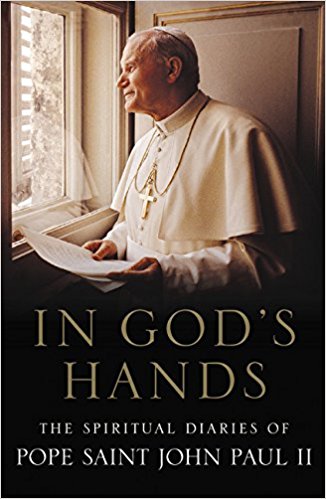

Yet, underneath all of this was a very spiritual man, the spirituality driving his insertion of the Catholic Church into the post-Second Vatican Council modern world. Only nine years after his death, he was declared a saint. This book aims to explain the pope’s spirituality in his own words, but it falls short.

Although the subtitle describes the book as the pope’s “spiritual diaries,” it is not. The book is a collection of notes the pope jotted down during years of spiritual retreats (1962-2003) as a Polish clergymen and then as pope during the annual Lenten retreats he took at the Vatican.

Some of the notes are labeled meditations and are several paragraphs long. But much of the book is composed of isolated sentences and phrases, things people jot down to jog their memories later on; and it is unclear whether these notes reflect the pope’s thinking or are a quick recording of the retreat master’s thoughts.

The pope, in his will, requested that these notes be burned but they were saved by his personal secretary, Msgr. Stanislaw Dziwisz – later the cardinal-archbishop of Krakow, Poland – who saw them as glimpses into the pope’s spirituality.

The most important glimpse, perhaps, was the pope’s ability to shut out his worldly concerns while on retreat to concentrate on his inner life. Except for a few simple references to the need for world peace and the threats posed by Marxism, communism, atheism and secularism to the church’s work in the modern world, the notes are devoted to spiritual issues.

Entirely Hers

Key among them is the pope’s devotion to Mary, the mother of God, exemplified in his motto “totus tuus,” Latin for “entirely yours,” taken from a Marian prayer. He shows interest in understanding her relationship to Jesus as her son and as God.

During his life, he often referred to her as being responsible for saving his life during the assassination attempt in St. Peter’s Square May 13, 1981. However, he only alludes to this once by naming his would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, in a brief section on forgiveness. The pope did visit Agca in prison and forgave him.

Another interesting point is his conviction, from his early years as a bishop, that the primary role of the episcopate is pastoral. While the notes may help scholars understand some of the spiritual issues important to the pope, it does not provide an in-depth look. Such a book has yet to be written.

Bono, a retired CNS staff writer, was Rome bureau chief during part of St. John Paul II’s pontificate.