by Bill Miller, Senior Reporter

JAMAICA — In the fall of 1984, Msgr. John Vesey was a Maryknoll missionary working with the indigenous people of southwestern Guatemala, but he became deathly ill with pneumonia. While bedridden, he slipped in and out of consciousness.

“I looked up and said, ‘Sisters, what are you doing here?’” he recalled. “They said, ‘Oh, you have to take your medicine.’ And it knocked me right out — like, immediately.”

Meanwhile, 20 paramilitary gunmen surrounded the house with orders to nab Msgr. Vesey as soon as he could travel. But Sister Alba and company believed that wouldn’t happen if he was sedated.

“They told me all this stuff later,” he said.

Protect Padre

Msgr. Vesey is retired but he still serves at Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary Parish, Jamaica.

He came to Guatemala six months before getting pneumonia to replace Father Stanley Rother. The priest from Oklahoma was targeted for abduction in 1981, also by right-wing paramilitaries.

Father Rother resisted, and the kidnappers fatally shot him.

But Sister Alba resolved not to see another priest murdered.

“Later she told me that her provincial superior made her promise that she would protect me with her own life,” Msgr. Vesey said. “And that’s what the sisters wanted to do. They said, ‘No. They’ve already taken one of ours. We will protect padre.’”

Grim History

Msgr. Vesey laughs repeatedly — as is his nature — when he recalls crazy events in his life. And the standoff between the sisters and gunmen is no exception.

But his countenance turns somber when he remembers Guatemala’s grim history during the government’s multi-decade fight with communist guerillas. Thousands of innocent people, including clergy and religious, died in the crossfire of this civil war.

Michael Lee, professor of theology at Fordham University, specializes in Church history in Latin America. He explained how bishops throughout the region gathered in 1968 in Medellin, Colombia, to ask hard questions about the Church’s role in their nations.

Subsequently, the bishops guided a shift toward more ministry among disenfranchised populations, Lee said.

Missionaries from Maryknoll and other orders got busy helping poor communities.

But requests on behalf of the people for things like better wages or labor unions were met with “extraordinary violence and repression,” Lee said.

Next, Cold War politics started to define U.S. foreign policy around the globe, including Latin America, Lee said.

President Ronald Reagan, he added, especially supported regimes or paramilitary groups battling communism in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala.

“And this was done despite some really horrific human rights records,” Lee said.

The violence in Guatemala spread to priests like Father Rother, or religious like Sister Dianna Ortiz. Kidnappers tortured and raped her, but she escaped.

“There was a colonel in Guatemala who, at one point says, ‘We make no distinction between communist subversives and the Catholic Church,’” Lee said.

What We Call Holiness

Msgr. Vesey said that during his bout with pneumonia, the 20 gunmen surely had enough brawn to carry him off, but Sister Alba deployed another obstacle.

More than 100 people surrounded the paramilitaries under the guise of keeping vigil for their padre. The catechists were unarmed, but the gunmen wanted to avoid a major incident, so they left.

Later, after Msgr. Vesey regained his health, the people surrounded him again, this time in their traditional attire, at the local cemetery for the All Souls’ Day tradition.

“I said to myself, ‘what pious people?’” he recalled. “‘Isn’t this wonderful,’ I thought, ‘that they’re coming with me to the cemetery?’

“But they were my bodyguards!”

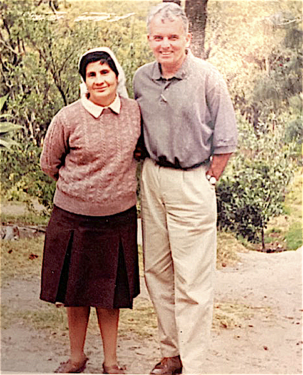

Msgr. Vesey still marvels at how Sister Alba peacefully orchestrated his safety. He said they remained friends after his 12 years in Guatemala.

Sister Alba went on to direct Catholic Charities in her diocese. She died a few years ago, Msgr. Vesey said.

“She was a really good and courageous human being,” Msgr. Vesey said. “To put your life on the line for somebody else — that’s what we call holiness.”

Later this year, Msgr. Vesey plans to visit his former parishioners and new friends in Santiago Atitlán.

But each day, before leaving to hear confessions, he stops to pray at a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“I pray for Sister Alba and I pray for all of the sisters,” he said. “I say ‘God, protect them.’”