JACKSON HEIGHTS — Claudia Salazar of Catholic Charities Brooklyn & Queens has no doubt her staff will soon encounter people hooked on drugs cut with the animal tranquilizer, xylazine — street name, “tranq.”

Salazar is vice president of Clinics, Recovery and Rehabilitative Services for CCBQ. For the past year, she has been overseeing the agency’s enhanced response to the opioid crisis.

Being on the lookout for tranq — infamous for how it rots human flesh — is now on the list.

As of late July, staff members had not yet received a case involving the drug. Still, Salazar said they know it’s a real threat, based on reports from federal and New York City law enforcement officers and health officials.

“It’s something that we’re not looking forward to seeing,” Salazar said, “but we know it’s coming.”

‘Another Eight Hours’

The opioid-xylazine combination conjures a more powerful, long-lasting high craved by people with addictions, said Andrew Karim, program director for CCBQ’s new Opioid Prevention Treatment program (OPT).

“It extends the fentanyl high for another eight hours,” Karim said.

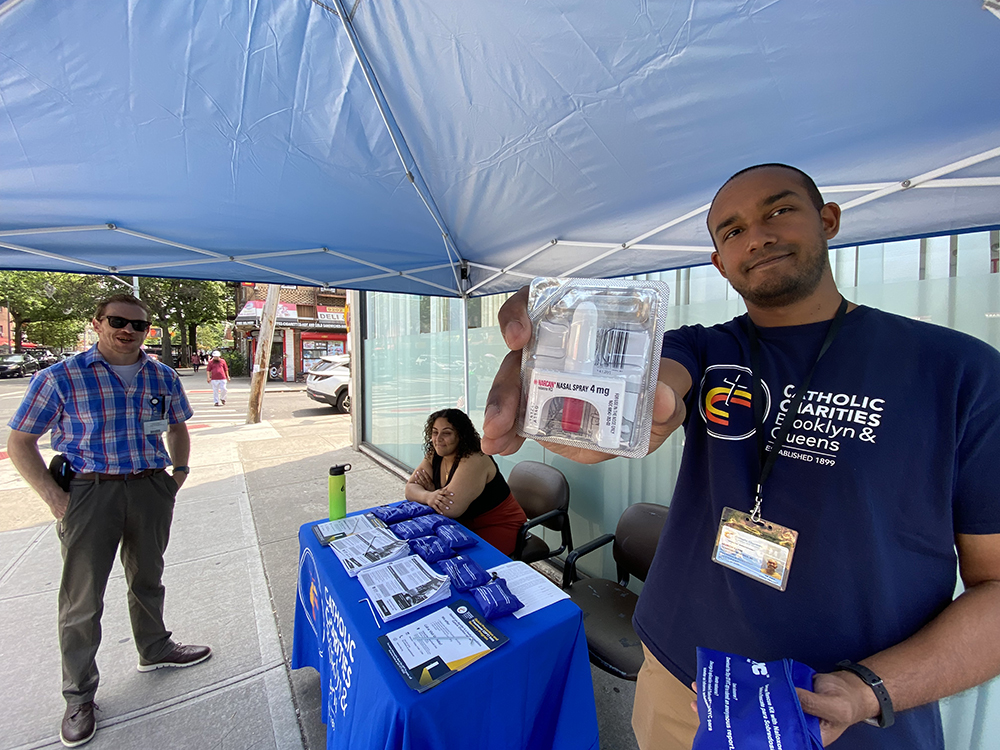

He discussed challenges posed by tranq July 25 during an OPT distribution of free NARCAN kits at CCBQ’s Corona Behavioral Health Clinic in Jackson Heights.

The kits carry two doses of the opioid-reversal medication, naloxone. They’re often called NARCAN kits because that’s the name of the company that manufactures the nasal applicators used to take the drug.

Naloxone is credited with saving the lives of thousands of people in the throes of opioid overdoses.

But since xylazine is strong enough to sedate a bear, it can contribute to fatal suppression of the central nervous system — like the ability to breathe — when combined with fentanyl or other drugs.

“It could be deadly immediately upon ingestion,” Salazar said.

Salazar added that because xylazine is not an opioid, naloxone is ineffective in treating tranq overdoses.

“You’ll still administer (naloxone),” she said, “because you don’t know what the person is overdosing from. It could be a combination of fentanyl, opioids, and tranq.

“If it’s just too much fentanyl, then maybe the (naloxone) will work. But you just never know what you’re dealing with.”

‘Zombie Heroin’

The CDC also advises first responders to go ahead and administer naloxone for an overdose.

But surviving an overdose doesn’t stave off other side effects of tranq, like the flesh-eating lesions that appear at the point of injection for people who take the drug intravenously.

A wound can become infected, leaving craterous scarring at best. At worse, the sores can become dangerously and painfully infected all the way into the bone, necessitating amputation.

“It’s gruesome,” Karim said. “That’s why they call it zombie heroin.”

‘Deadliest Drug Threat’

Drug Enforcement Administration officials began noticing around 2010 that xylazine was becoming a “drug of abuse on its own” in Puerto Rico, according to an October 2022 report.

Chinese suppliers sell the drug online for $6-$20 per kilogram, the report said.

Drug dealers now use the tranquilizer to “adulterate” illicit drug cocktails because it lets them cut back on “the amount of fentanyl or heroin used in a mixture,” the DEA reported.

Consequently, “xylazine is making the deadliest drug threat our country has ever faced, fentanyl, even deadlier,” said DEA Administrator Anne Milgram.

She added that “the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco Cartel in Mexico, using chemicals largely sourced from China, are primarily responsible for the vast majority of the fentanyl that is being trafficked in communities across the United States.”

Good News, Bad News

Dr. Rahul Gupta, the White House drug czar, while testifying before Congress on July 27, said the number of deaths related to the U.S. opioid epidemic shows signs of “flattening.”

That is welcome news considering the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 107,735 Americans died between August 2021 and August 2022 from drug poisoning — 66% of them due to opioids.

But Dr. Gupta warned that xylazine “threatens the progress made to save lives and end the overdose epidemic.”

He referred to a CDC study released in June.

It showed that, from a sampling of 20 states and the District of Columbia, “the monthly percentage of illicit fentanyl overdose deaths involving xylazine increased by 276% between January 2019 and June 2022.”

New York state did not contribute data to that sampling.

But, in the same study, the CDC reported that “death certificate data” showed xylazine was involved in 735 opioid deaths in New York during the same test period.

Closer to Home

Bridget Brennan, special narcotics prosecutor for New York City, reported recently that fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine are increasingly mixed with xylazine, “in various combinations.

“It has been present in the city for more than a year and is now beginning to saturate the street market,” Brennan said in her annual budget report.

The illicit work is done at drug packaging and stash locations, many of them in the Bronx, but not all.

For example, Brennan’s office noted that in January, federal agents seized nearly 20 kilograms of fentanyl cut with xylazine (about 44 pounds) from a storage unit allegedly rented by a man from Jamaica, Queens.

Thus, Salazar said, “We’re preparing.”

“Like fentanyl,” she continued, “and any other drug, for some reason, somehow, it always starts up upstate, and then it trickles into the city.”

No Tranq Treatment — Yet

A Catholic response to this crisis depends on extending care and dignity to clients, Salazar said.

The OPT program got underway last fall with a $3.75 million federal grant offering services that help people enter and stay in recovery.

Still, that’s hard to do without the necessary tools.

For example, OPT’s “medicated assisted treatment” plan involves drugs that ease withdrawal symptoms.

But, according to the Food and Drug Administration, people addicted to xylazine, “may experience severe withdrawal symptoms,” if they try to get clean.

And, in a “Dear Colleague” letter to physicians, the agency noted that “no medications have an FDA-approved indication” to treat xylazine withdrawal.

Also, there is no antidote like naloxone to reverse the effects of tranq.

Congress is crafting legislation to fund research into new drugs that can treat overdoses and withdrawals of tranq.

Also, New York state lawmakers are considering legislation to put xylazine on the list of controlled substances. The bill’s versions are A-5914 in the Assembly and S-5439 in the Senate.

Controlled substance designation identifies a drug as having the potential for abuse by using it in a way not originally intended.

Xylazine, for example, is intended to sedate animals in veterinary care, not to pad another drug to enhance its illicit appeal.

So designating it as a controlled substance will enable officials to regulate its use, manufacturing, and distribution to prevent drug abuse.

Salazar, Karim, and their colleagues are eager for government-funded science to make that progress.

“That’s what the conversation is about now because this is fairly new,” Karim said. “And we’re trying to understand why it’s becoming so big.”

‘A Non-Shaming Place’

Meanwhile, CCBQ continues building the OPT program and its availability at five behavioral health centers.

The free NARCAN kits distributed by CCBQ on July 25 were procured through a partnership with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The OPT team also plans to hold more distribution events at the Jackson Heights location, and also CCBQ’s four other behavioral health centers in Flatbush, Jamaica, Far Rockaway, and Glendale, Salazar said.

“Despite their challenges, you treat people like human beings and with respect,” Salazar said. “This is why we have beautiful facilities. We want people coming in and feeling welcome. It’s a non-shaming place.”