WASHINGTON — After just six minutes of bidding at Sotheby’s auction house May 17, the world’s oldest Hebrew Bible, known as the Codex Sassoon, sold for $31.8 million, one of the highest prices for a book or historical document ever sold at an auction.

Concerns for months that the buyer of this 1,100-year-old text could simply keep it in a private collection out of public view were almost immediately laid to rest when Sotheby’s announced that the buyer was the American Friends of ANU — Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, made possible from a donation from Alfred H. Moses, a former ambassador to Romania, and his family.

“The Hebrew Bible is the most influential in history and constitutes the bedrock of Western Civilization,” Moses said in a statement. The 93-year-old Washington resident said he realized the historic significance of the Codex Sassoon and that it had been his mission to see that “it resides in a place with global access to all people.

“In my heart and mind that place was the land of Israel, the cradle of Judaism, where the Hebrew Bible originated. In Israel at ANU, it will be preserved for generations to come as the centerpiece and gem of the entire and extensive display and presence of the Jewish story,” he added.

This is good news to James Hanges, professor and chair of the comparative religion department at Miami University in Ohio. He told The Tablet May 18 that he “hoped this is what would happen.

“I think it would be hard to find a more appropriate place,” for this text than the ANU Museum of the Jewish People, he said.

Prior to the sale, Hanges said he would be watching to see who would buy it, noting it would likely be out of reach for a vast majority of museums around the world and that a private owner could loan it to a museum, but also might not.

“It depends on their sense of social obligation,” he told The Tablet in April.

The manuscript, which was expected to sell for $30-$50 million, was named for its one-time owner, David Solomon Sassoon, a collector in England.

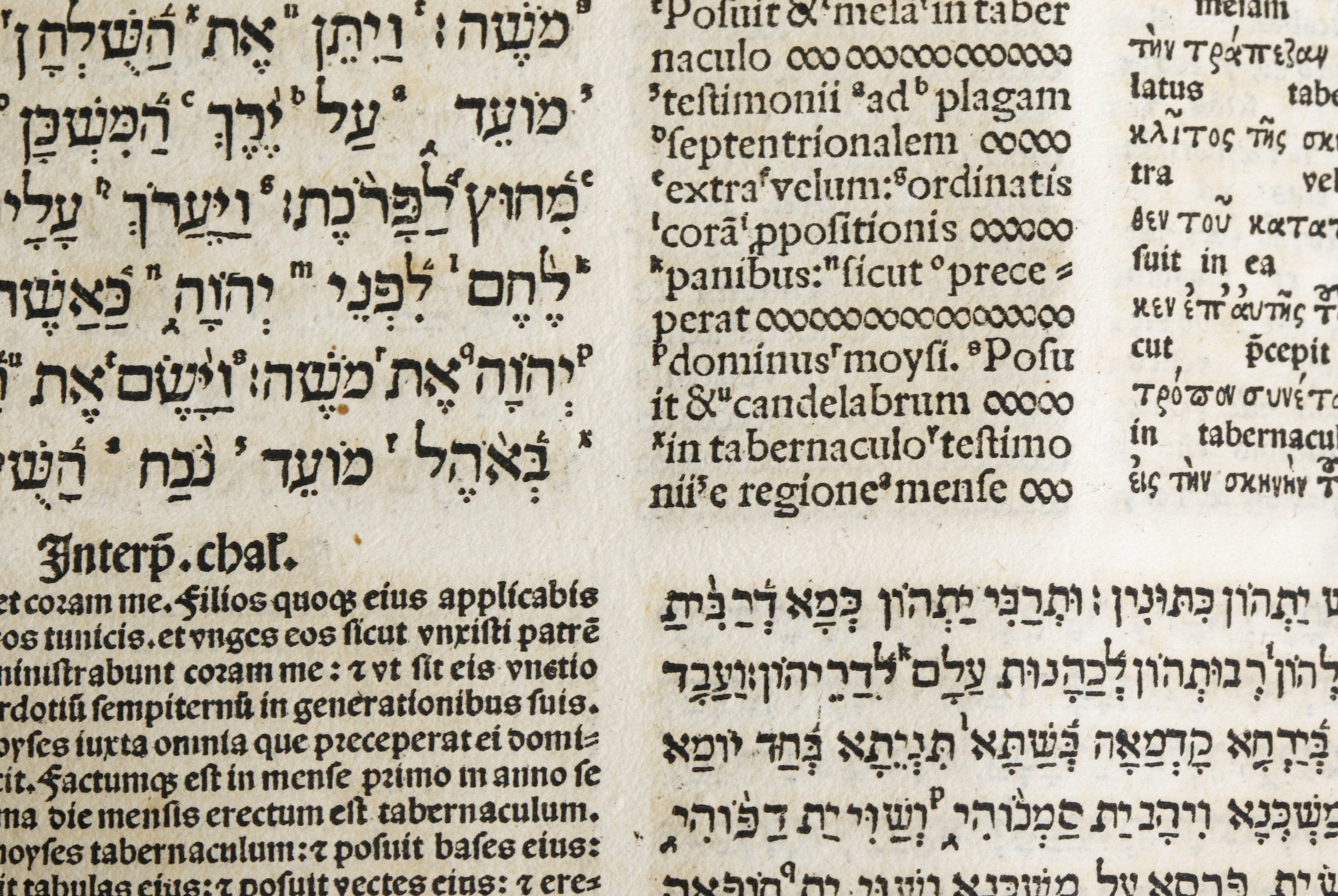

Since 1989, this codex — which includes most of the original text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, save for 12 pages from the Book of Genesis — has been owned by a Swiss collector. The travels of this ancient text, prior to 1989, could almost write a book.

According to historians, a scribe wrote the Codex Sassoon in the late 9th or early 10th century, and the manuscript made its way to a synagogue in present-day Syria. After the synagogue was destroyed around the 13th or 14th century, the text disappeared for the next 600 years. It resurfaced in 1929, was purchased by Sassoon and remained in his family for about 50 years before being sold a few more times.

Researchers say the bound volume of 400 pages of ancient parchment provides the basis of biblical translations used today by Jews, Christians, and the Islamic faith that teaches that the Torah and Psalms contained within the Hebrew Bible are divinely revealed.

A key aspect of this manuscript, beyond its age and near-complete collection, is that it also contains something akin to a pronunciation guide known as the Masorah, compiled by Hebrew Bible scholars called the Masoretes.

This guide alone is a key part of the manuscript, Hanges said in April, noting that the manuscript has particular significance since it was made at a time when Jewish scholars were trying to make Hebrew Bible texts more accessible to Jews who were living around the world and did not always speak Hebrew.

The notes in the manuscript essentially make the text accessible because they show the reader how it should be read. Hanges also said this guide provided a way for the Jewish community to solidify itself and preserve its unity amid persecution.

The day after the sale, Hanges reiterated that the value of this text is “what it means to the Jewish community” and how it provides a “sense of continuity and development over time.”

If he travels to Israel, he said, it would be well worth the visit to the museum to see this historic text.

The museum, which displayed the text in April for timed visits, as part of the Bible’s pre-sale tour, announced May 18 on its website that the ancient text would be part of its core exhibition and permanent collection.

The announcement said the story of the codex’s mere existence today “demonstrates the meaning of survival, endurance, resilience, perseverance, and dedication, much like the Jewish people.”

“The Codex Sassoon Bible is a powerful and meaningful manuscript of faith, history, and culture,” said Daniel Pincus, president of American Friends of ANU. “As the basis of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Hebrew Bible is a seminal text to countless people, and one of the most important discoveries of our time.”