By Mark Zimmermann

WASHINGTON (CNS) — The beaches of Normandy, France, seem a long way from Bethel, Conn., but many of the lessons about life that Joseph P. Vaghi Jr. learned in his home town probably prepared him to take part in the D-Day landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Vaghi’s family and his Catholic faith have always been central to his life.

He and his eight siblings were raised with a strong Catholic faith taught to them by their parents, Joseph Sr. and his wife, Battistina, who had come to the United States in 1906 from Italy.

On Sunday, “we’d march one behind the other to church, which was one block from where we lived,” Vaghi recalled.

The elder Vaghi, who ran his own woodworking company, had an indomitable spirit shaped by his struggles to succeed in America as an immigrant, said his son and namesake.

During World War II, five of the Vaghi sons served in the military, and the sixth and youngest served after the war.

Joseph Vaghi Jr. joined the Navy and was commissioned an ensign. He completed a degree in philosophy at Providence College in Rhode Island and went to midshipman’s school at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

He was assigned to duty as a platoon commander with the Naval Amphibious Forces. First he trained along the Atlantic seaboard, then on the coast of England.

“We knew a good deal about what we were going into. We were so well-prepared,” he told the Catholic Standard, newspaper of the Washington Archdiocese.

Vaghi, who will turn 84 June 27, received a special assignment — to be a beach master in the Normandy invasion.

“My job was that of a traffic cop, on a very heavily trafficked intersection, with everything coming from every direction,” he said.

A correspondent for The New Yorker magazine quoted an eyewitness as saying that Vaghi was the first off his landing craft and charged onto the beach like a football player running with the ball.

“When I went into Normandy, I had absolutely no fear, because I knew God would look after me. If he wanted me, that would be it,” he said.

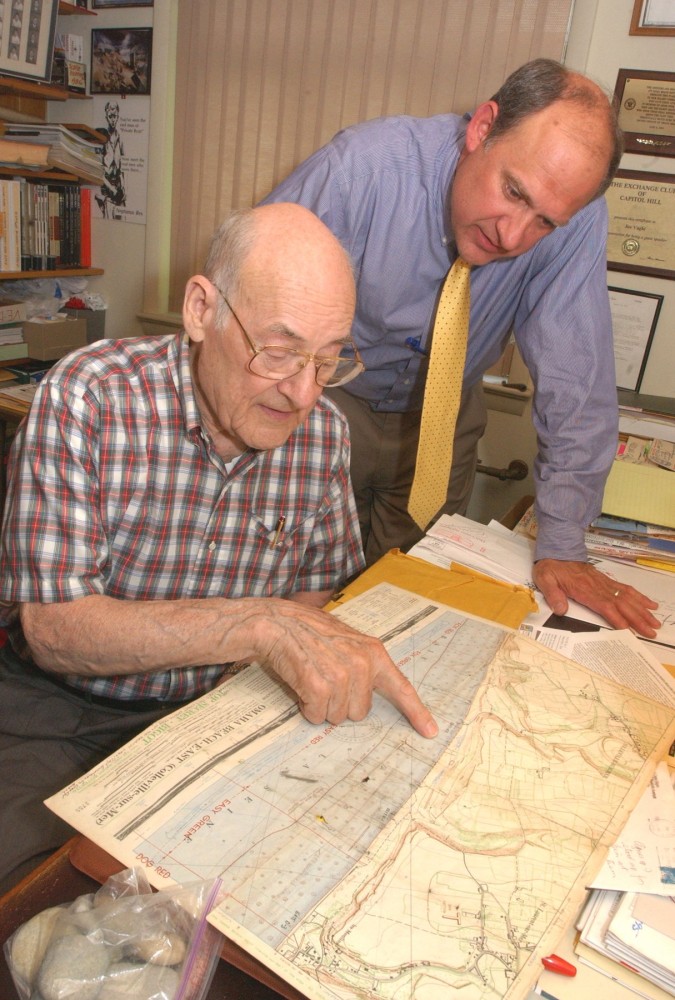

Vaghi still owns the map he used to direct men onto the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach.

“I landed here. … I would send traffic up this way,” he told a visitor, pointing to the map.

The chart is worn and creased from being in his pocket as he landed on the beach. It includes detailed markings of German obstacles in the tidal area, the beach and surrounding cliffs and countryside, reflecting the bravery of spies who scouted the area beforehand.

“That’s where we broke through the German Atlantic wall, right through that point,” said Vaghi, pointing to a section of his map.

He remembered the heroism of a sergeant who had yelled, “Follow me,” after that man had shot an American torpedo that blew a gap in a barbed wire fence above the sand dune. That wave of troops charged through a mine field that killed or wounded many of them.

“Once this heroic act of the sergeant was accomplished, the Army began its offense against the Germans as the GIs began to attack the Germans’ strong points and began to fan out for their movement into the countryside of Normandy (and) the Battle of Normandy was under way,” Vaghi wrote later.

Vaghi remained on that beach, directing the traffic for successive waves of Allied invaders and helping care for the wounded through June 29, celebrating his 24th birthday there. His unit lost 23 men in the invasion.

Today, Joseph Vaghi Jr. said he “prays all the time” for the men in his unit who died.

“Like myself, they were young kids. We did what we were told to do, trained to do. … We had great men,” he said.

He noted how Americans on the home front also made sacrifices for the war effort, collecting aluminum and knitting socks and gloves.

Ensign Vaghi, who was later promoted to lieutenant, earned the Bronze Star for his heroism at Normandy when he pulled gasoline cans and boxes of hand grenades from a jeep that had caught fire from enemy artillery, preventing further explosions and casualties.

In 1945, he volunteered to serve in the Pacific theater and participated in the Easter Sunday invasion of Okinawa, Japan.

In 1959, he retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of lieutenant commander.

After the war, he got married. He and his wife, Agnes, had four sons, once of whom is a Washington pastor. His wife died in February of this year of complications from a stroke. They had been married 57 years.

Armed with a degree from the School of Architecture at The Catholic University of America in Washington, he started his own architectural firm and designed and built a home for his growing family in the Washington suburb of Kensington, Md.

Vaghi said that he feels somewhat uncomfortable with the label “The Greatest Generation,” the title of news anchor Tom Brokaw’s best-selling book about the heroics of those who served in World War II.

He doesn’t want to leave out the men and women “who don the uniform today and go to battle.”

“Whether you go to battle in Normandy, Okinawa or in Iraq, we’re all God’s children, and it’s important we’re recognized as such,” he said.