By Elise Ann Allen

ROME – This week the Vatican’s Academy for Life issued a new text on a series of bioethical issues, including the provision of food and hydration for patients in a vegetative state, which marks a modest departure from the Vatican’s previously held position on the issue.

Published Thursday by the Pontifical Academy for Life (PAV), the volume is titled, “Small Lexicon on End of Life,” and covers a variety of bioethical issues.

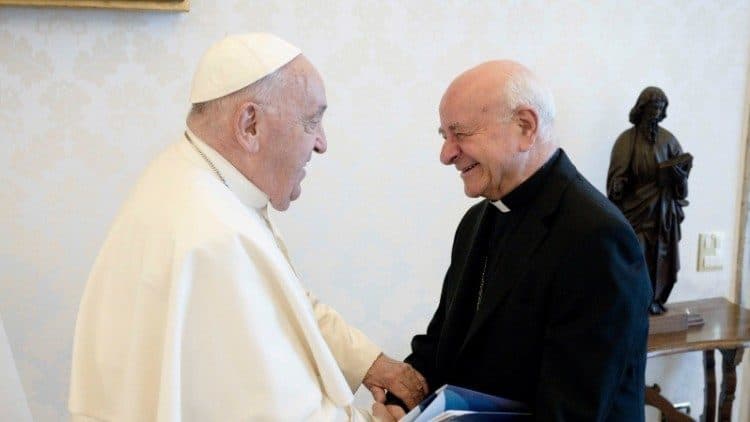

According to an introduction by Italian Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the PAV, the volume has the aim of “reducing at least that component of disagreement that depends on an imprecise use of the notions implied in speech.”

Namely, Archbishop Paglia referred to “the statements that are sometimes attributed to believers and which are not rarely the result of cliches that have not been adequately scrutinized.

Among other things, the 88-page text reaffirms a blanket “no” to euthanasia and assisted suicide, but it also shifts toward a new openness from the Vatican when it comes to so-called “aggressive treatment,” specifically the requirement to provide food and hydration to patients in a vegetative state.

In section 13 of the volume, which deals with this issue of food and hydration, a reference is made to the recently published declaration of human dignity from the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF), Dignitas Infinita.

In Dignitas Infinita, the DDF reiterated the need to avoid “every aggressive therapy or disproportionate intervention” in the treatment of patients with serious illnesses.

Likewise, the PAV’s new volume also invoked the July 2020 letter Samaritanus Bonus, which among other things mentioned “the moral obligation to exclude aggressive therapy” treatment plans.

The volume noted that the food and hydration prepared for vegetative patients are prepared in a laboratory and administered through technology, and thus do not amount to “simple care procedures.”

Doctors, the text said, are “required to respect the will of the patient who refuses them with a conscious and informed decision, even expressed in advance in anticipation of the possible loss of the ability express oneself and choose.”

They noted that for patients in a vegetative state, there are some who argue that when food and hydration are suspended, death is not caused by the illness but rather by those who suspend them.

This argument, the PAV said, “is the victim of a reductive conception of disease, which is understood as an alteration of a particular function of the organism, losing sight of the totality of the person.”

“This reductive way of interpreting disease then leads to an equally reductive concept of care, which ends up focusing on individual functions of the organism rather than the overall good of the person,” the volume says.

To this end, it quoted from a November 2017 speech from Pope Francis to members of the PAV in which he said that technical interventions on the body “can support biological functions that have become insufficient, or even replace them, but this is not equivalent to promoting health.”

“Therefore, an extra dose of wisdom is needed, because today the temptation to insist on treatments that produce powerful effects on the body, but which sometimes do not benefit the integral good of the person, is more insidious,” the text said, continuing the quotation of Pope Francis.

The PAV insisted that this position does not conflict with the position previously taken by the DDF on the issue of food and hydration, which was issued in 2007 in response to bishops in the United States on the moral obligation to provide food and water to patients in a vegetative state, even through artificial means.

In their brief response, the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith held that even in a situation where there’s moral certainty that a patient will never recover, it was not permissible to withdraw food and water, as doing so would effectively allow the person to die of dehydration or starvation.

The position taken in the PAV’s new document marks a shift toward a new openness from this position, however, in their volume, the PAV insisted their stance does not mark a departure from the 2007 decision and, to this end, cited “ethically legitimate” reasons for suspending treatment included in the then-CDF’s response.

Among other things, the PAV noted that the then-CDF said it was possible to suspend treatment when it was no longer seen as “effective from a clinical point of view,” meaning when bodily tissues are “no longer able to absorb the administered substances,” and when it causes the patient “an excessive burden or significant physical discomfort linked, for example, to complications in the use of instrumental aids.”

In a bid to illustrate continuity in the Vatican’s position on the topic, the PAV volume said this last point from the 2007 response refers to the question of proportionality in the administration of treatments, and it argued that the DDF’s new document Dignitas Infinita, published in April, “moves along the same lines.”

The PAV’s new “lexicon” suggested that Dignitas Infinita be interpreted in a “long-term and broad-based perspective,” and it notes that the DDF text “does not elaborate an overall reflection on the relationship between ethics and the legal sphere.”

On this point, “the space therefore remains open for the search for mediations on the legislative level, according to the principle of ‘imperfect laws,’” the PAV said.

In terms of legal mediation on the issue, the PAV said, “In addressing the issues evoked by individual words, this lexicon takes into account the pluralistic and democratic context of the societies in which the debate takes place, especially when it enters the legal field.”

“The different moral languages are not at all incommunicable and untranslatable, as some claim,” the PAV said, insisting that dialogue is possible among those with differing views of the issue.

By allowing the space to be kept open for research on legislative mediation on the topic, Paglia in his introduction said that “in this way, believers assume their responsibility to explain to everyone the universal (ethical) sense disclosed in the Christian faith.”