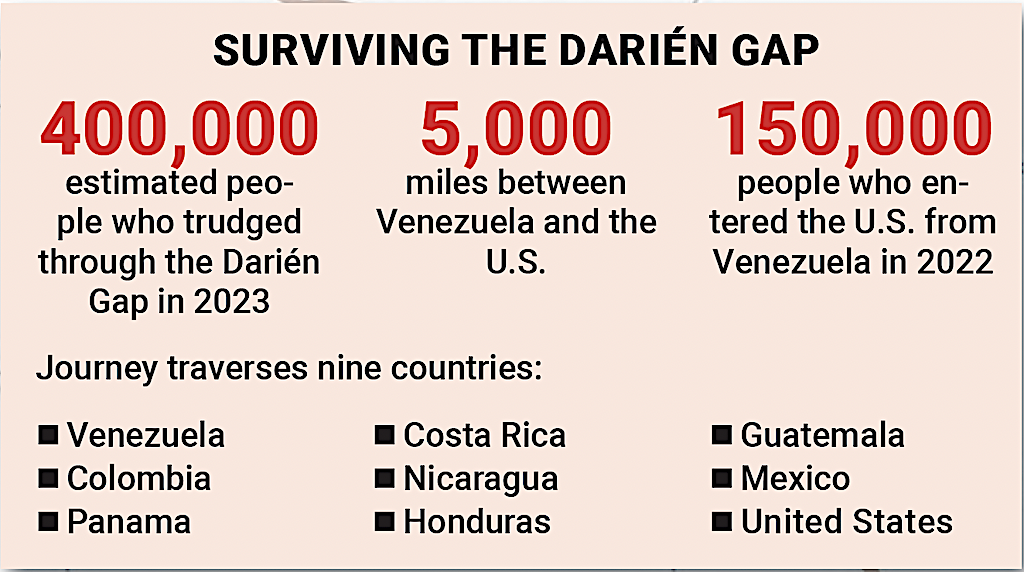

SUNSET PARK — Marlin and Josibel knew the 5,000-mile hike from their homes in Venezuela to the United States would be tough, especially traveling with children.

But the most difficult part was crossing a deadly stretch of Panama’s jungle. Communicating through translators, both women described their harrowing ordeals in this place — the Darién Gap.

Marlin (pronounced Marlene), traveled with her 14-year-old son. To protect their identities, the women asked The Tablet not to show their faces.

She said they clung to ropes to cross a river and trudged through steep, mud-clogged trails in the steamy jungle. Her feet, constantly wet, became blistered.

Coming out of the jungle, she thought of returning to Venezuela, but also knew the only future in her homeland was political persecution.

“Move forward,” became Marlin’s mantra. “No looking back.”

Josibel and her family originally chose Colombia as their new home, but the government there sought to limit immigration.

The family, including her husband, their daughter and three sons, ages 4 to 14, and her parents, went back to Venezuela. But authorities there called them traitors and denied entry.

So, they decided to journey to the United States, even with their children, Josibel said. It’s not an ordeal she would wish on anyone, she added, but it was worth it for her kids.

Political uncertainty in Venezuela contributes to the Western Hemisphere’s worst humanitarian crisis in years, according to the group Project HOPE. This organization provides humanitarian medical aid in areas affected by natural and man-made disasters.

“Venezuelans are running out of food and have no means to buy more,” Project HOPE said in a recent statement. “Hospitals often lack medicines and basic supplies, and we are seeing increasingly alarming reports of malnutrition amongst the children of Venezuela.”

Josibel and Marlin come from different towns, so they did not know each other until recently. They arrived in New York City earlier this fall after traveling by bus from the border with Mexico.

They recounted their journeys recently during a break in job-training courses conducted by Catholic Charities Brooklyn & Queens (CCBQ) at St. Michael’s Parish in Sunset Park. CCBQ staffers served as their translators.

In separate conversations, the women said deciding to leave Venezuela was hard, but they had no other options.

Both had chosen to not support the ruling political force — the United Socialist Party of Venezuela. Consequently, their families had no futures.

Marlin said she could not get a government-issued ID card needed to receive services, such as an education for her son. He had not been to school for three years, she said.

Josibel’s husband, a warehouse worker and delivery driver, was harassed on the job by police and kept from completing his routes, she said.

These two families are among an estimated 400,000 people who have passed through the Darién Gap so far this year, according to the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. Almost half of those people are children.

An unknown number of people don’t make it through the jungle. They either turn back, or die.

Marlin said she didn’t see any human remains, but there were reports of people drowning along the route.

“When the river is high, and you can’t hold on to the ropes, you crash on the rocks and get killed,” she said.

Josibel’s family could not escape witnessing the tragedies.

She tried to distract the children with candy. That worked with the smallest boys, ages 8 and 4. Still, she couldn’t stop her daughter, 14, and older son, 12, from seeing the bodies.

Josibel wept as she explained her daughter takes cleanliness seriously, but that was impossible in the jungle.

Other dangers abound in the Darién Gap, said Volker Türk, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In a statement released in September, he said migrants face multiple abuses, including sexual violence, “which is a particular risk for children, women, LGBTI people, and people with disabilities.”

There are also murders, disappearances, trafficking, robbery, and intimidation by organized crime groups, Türk said.

Marlin and Josibel were both robbed in Mexico by armed men.

Josibel said a man tried to shoot her husband, but the gun jammed. Her 4-year-old jumped up out of fear, and the robber shoved him. The child suffered a deep cut on the head, Josibel said.

Her family finally reached the Rio Grande, but border guards at first wouldn’t let them pass. They had been walking in the desert for several hours with no water, and Josibel thought she could go no farther.

The guards then tossed bottled water over the fence to them. Eventually they crossed. Officials then put them on buses to New York City.

Türk urged nations to address the problems causing people to leave their homes and embark on perilous journeys “in search of safety and a more dignified life for their families.”

Meanwhile, the plight of the migrants has become like a political football, kicked about in partisan debate. Some New Yorkers protest the busloads of asylum-seekers at various shelters set up for them.

But rancor also swirls within the Democrat Party. New York Mayor Eric Adams has warned that the city can’t absorb any more immigrants without the risk of economic demise.

He has called upon President Joe Biden, a fellow Democrat, to end the crisis, but it continues.

Josibel and Marlin live in shelters with their families while awaiting the outcomes of their lengthy legal proceedings. CCBQ has referred them to Catholic Migration Services, which is helping them.

“Questions as to why they are here are not for me to answer,” said Richard Slizeski, CCBQ senior vice president of mission. “We’re here to help people who are in need.

“When we can respond in a Christ-like way to their needs, I feel we’re doing what the Church is asking us to do.”

Josibel and Marlin, meanwhile, can’t work, which adds to their stress. Marlin was given an ankle monitor to wear until her first court hearing in March. She said it hurts and makes her look like a criminal, which is embarrassing.

Still, all the children are in school, much to the relief of their mothers.

Marlin thanks God for CCBQ, and for protecting her son on the journey.

“He never abandoned me,” she said. “I always managed to find bread, even if it was just bread to give my child.”