WINDSOR TERRACE — The journey to sainthood in the Catholic Church involves several steps.

The process cannot begin until five years after the candidate has died. If five years sounds like a long time to wait, consider this: The waiting period used to be 50 years. The pope can cut the waiting period, as Pope Benedict XVI did for St. John Paul II when he allowed the process to begin a month after the pontiff’s death in 2005.

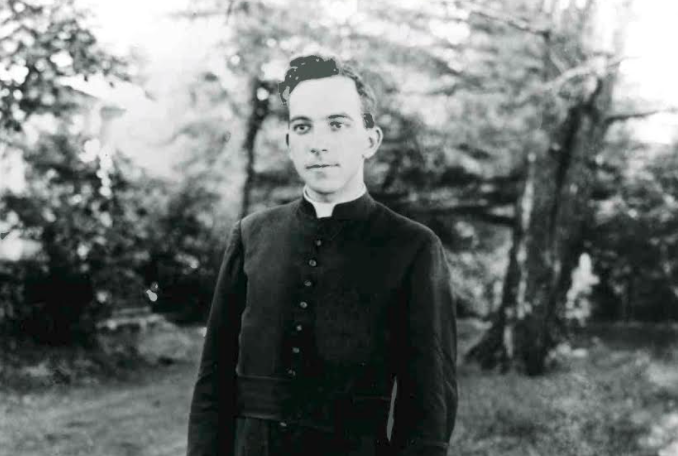

The Diocese of Brooklyn is currently advocating for sainthood for two individuals: Bishop Francis Xavier Ford (1892-1952) and Msgr. Bernard J. Quinn (1888-1940). Bishop Ford was a Maryknoll priest who traveled to China in 1918 to serve as a missionary there. In 1950, he was thrown into a prison camp by the Communist government. He died in captivity 1952. Msgr. Quinn was known for his fight against racial injustice. He established the first parish for Black Catholics in the diocese, St. Peter Claver Church, Bedford-Stuyvesant, in 1922.

Once the five-year waiting period is up, the bishop of the diocese where the person died (unless particular circumstances, recognized as such by the Sacred Congregation, suggest otherwise) can authorize the opening of an investigation into whether the individual would be a good candidate for sainthood.

If the initial investigation determines the person qualifies for possible sainthood, the bishop can declare the person a Servant of God and issue a request to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints at the Vatican for permission to officially open a case.

At this point, the hard work begins. A theological commission is formed to investigate the individual’s life, including their writings and accounts of contemporaries if any are available. The investigators can leave no stone unturned to make sure there is nothing disqualifying in the person’s life.

Father Kevin Hanlon M.M. a Maryknoll priest, is a member of the commission investigating Bishop Ford’s life and writings.

“We have to write an account of his life. We try to read everything he wrote,” Fr. Hanlon said.

“It’s not the same thing as a biography. It is not to tell charming stories. It is to give an accurate account.”

The materials gathered have to include basics like the person’s birth certificate and proof of sacraments such as a baptismal certificate. That task isn’t as hard as it might sound. “Fortunately, the mother of all record-keepers is the Catholic Church. And Bishop Ford would have had to present these documents to get into the seminary,” Father Hanlon said.

The process of canonization also involves money.

“It can be an expensive proposition,” said Ed Wilkinson, editor emeritus of The Tablet, who is familiar with the effort being made on behalf of Bishop Ford. “It takes a lot of time and expense to conduct an investigation and gather documentation. And you have to send everything to Rome.”

The process can be cost-prohibitive for a diocese lacking deep financial resources — a fact that many Catholics find troubling.

At the end of the diocesan phase, the documents and other materials are gathered together and presented to the Holy See for officials to review.

Bishop DiMarzio personally presented the materials on Msgr. Quinn to the Holy See in November of 2019. The materials were contained in a large box.

“It took a long time to get to that point,” he said, emphasizing that patience is often required when advocating for sainthood for an individual. “We started the process 10 years ago when Msgr. Jervis asked us to look into it.”

Msgr. Paul Jervis, the pastor of St. Francis of Assisi-St. Blaise Parish, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, is the author of “Quintessential Priest, the Life of Father Bernard J. Quinn,” a book about the cleric.

The Congregation for the Causes of Saints examines the evidence presented by a diocese and if it approves of the person, passes its findings on to the pope. If the pope agrees with the congregation’s finding, he can declare that the candidate can be called “venerable.”

The next step in the process is beatification. A person can be beatified by the pope after a miracle is attributed to him or her.

“In most cases, it’s a medical miracle. Someone is cured of a sickness after they prayed for intersession or their burden is eased in a significant way,” Bishop DiMarzio said.

Advocates must have proof on their side. “They don’t just take your word for it. Doctors have to examine the evidence,” Wilkinson said.

There is an exception, however — in the case of a candidate for sainthood who died a martyr, a miracle is not necessary for beatification.

Beatification is significant because it is the final step before sainthood. Beatification is usually celebrated with a Mass. Father Michael McGivney (1852-1890), founder of the Knights of Columbus, was beatified at a Mass at the Cathedral of St. Joseph in the Diocese of Hartford Connecticut, on Oct. 31. The effort to elevate Father McGivney to sainthood began back in 1997.

With beatification, the candidate is considered to have entered heaven. A beatified person is called “Blessed.”

The final and most important step is canonization. That is when the church declares a person to be a saint. To get to this point, a second miracle, different from the first, has to be confirmed. For martyrs, proof of one miracle is required at this point.