Art seems to be to Lucinda Grange the last reward in a singular extreme journey. The adrenaline, the forbidden, the temptation to steal unseen views and bring new perspectives into our ordinary lives, is as important for the sui generis artist as the artwork itself.

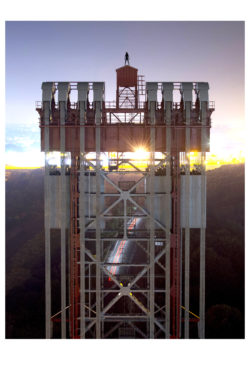

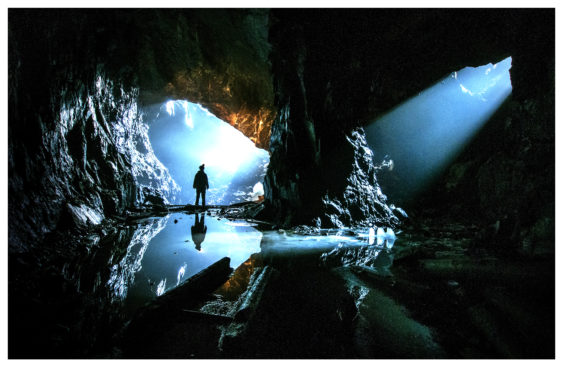

Halfway between a “roofer” – a subculture of youth who illicitly sneak into high-rise buildings to catch the most amazing and dangerous views – and an urban tomb-raider-superwoman artist documenting the forbidden archaeology of the cities, at 30, Grange has gathered some amazing photographs under her belt.

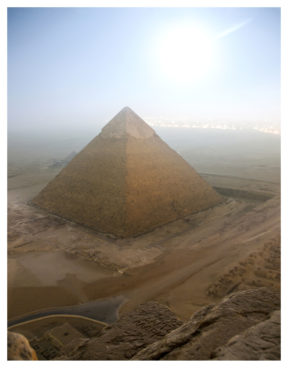

She trespassed into the Giza Pyramid complex to climb the Great Pyramids in August of 2013, during the military curfew and violent unrest following the coup d’état that removed former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood from power. And she has posed on the top of one of the eagles of the Chrysler Building – like Margaret Bourke-White and Annie Leibovitz before her – in an already iconic photograph that Gothamist editorial director Jen Carlson described as “beautiful terrifying.”

In “City Cross-Section,” Grange’s first solo show at the Lyle O. Reitzel Contemporary Gallery on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, the New York-based British urban photographer – equipped with a great eye and daredevil abilities – dissects the anatomy of the cities with a clean cut to “expose and share the deepest underbellies and highest peaks of the very place we live and love.”

“City Cross-Section” is an ongoing project by Grange, whose works spans over a decade, and the show, which opened last month runs through Feb. 28.

Those who know their city like the palm of their hand – Manhattan, Berlin, Paris – will find themselves re-mapping their urban memories after visiting Grange’s show. For she returns to her audience the visual palimpsest of urban architecture from the most challenging perspectives – one of the details of her photo compositions which is worth noticing because she displays a solid use of the vanishing points. This is, in fact, perfectly assembled and displayed in six photocollages, in which she tore and collated different topographic levels – from underground to aerial views – of landmarks like the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the Manhattan Bridge, the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, or Berlin’s iconic Brandenburg Gate, with a section of a 50-foot underground roadway network, designed by Hitler’s architect Albert Speer in the Tiergarten, which remains closed to the public.

In a recount of her trip to Egypt, Grange wrote: “Despite the revolutionary turmoil that surrounded us, this place felt a world away. The top of the great pyramid was full of engravings. People’s names, the names of those who had climbed before, in English, Arabic, all different scripts and languages. One read ‘TOURING CLUB’, making me think of lads-on-tour type stags. We were there for a little over two hours before we packed our cameras to move on. The photography felt rushed and messy, but I didn’t mind. This wasn’t about producing images, it was about the experience, the journey to get there. We’d managed that, now we just needed to get down the pyramid, out and back to the UK safely.”

The result, as visitors to the show can see, is not “rushed and messy,” but the photograph titled “Summit” (2014), an exceptionally compelling view of the pyramid veiled by an eerie sandy atmosphere. Nevertheless, that quote brings to our attention one of the constant concepts of Grange’s artwork: the idea of “producing images” as a sub-product of a more visceral experience, one in which art is a physical outgrowth, a remaining or random document. While this is not new, in Grange, artwork finds a particular approach of cinematic proportion, bouncing between the still photo of a science fiction movie or superhero graphic novel and a trace of a wondrous intimate expedition into the hidden corridors of cities as a metaphor of the most honest voyage of temptations through the shadows and lights, fears and confidences of her inner self.