ROME – At a 2007 meeting of the Latin American bishops in Aparecida, Brazil – where then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio would play an instrumental role that would later serve as a catalyst for his election to the papacy – he’s said to have remarked that “Oscar Romero is saint and a martyr, and if I became pope I would canonize him.”

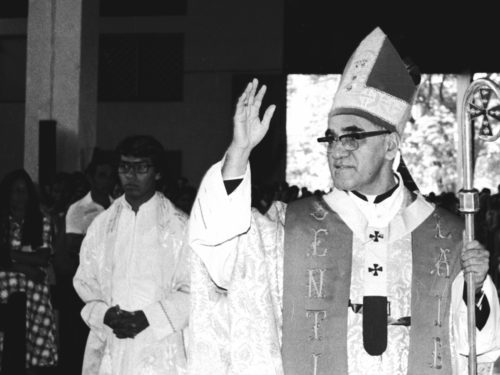

Now, just over a decade later, Pope Francis did just that on Oct. 14. In the presence of more than 60,000 attendees, he formally declared that the Catholic Church recognizes Oscar Romero, along with Pope Paul VI and five other individuals, as saints.

Yet despite the fact that he was gunned down while celebrating Mass, Romero’s eventual canonization was by no means guaranteed. Following his bloody martyrdom in 1980, it would take over three decades for the Vatican to advance what those on the ground in his native El Salvador believed long before: that the soft-spoken man who became a voice of conscience for the entire nation is, indeed, a saint.

Born in 1917 into a family of seven siblings, at age 6 a young Romero found himself in deep prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. At age 13, he would follow that spiritual tug into the seminary, where he was eventually sent to Rome for his studies before returning home at age 26 and spending the next two decades in parish ministry. In 1970, he was made an auxiliary bishop of San Salvador in 1970, and then named bishop of Santiago de María in 1974 where his flock was made up of the rural poor.

Throughout Romero’s early years he was widely viewed as a conservative, but it was his work alongside farmworkers, particularly coffee harvesters, that began to open his eyes to their reality, which would gradually alter both his political and theological perspectives.

Yet it wasn’t their mere poverty that scandalized him, but rather, the way in which they were taken advantage of by landowners and then targeted by the military when they sought to protest their abuse policies.

At one point, following the government organized massacre of farmworkers, Romero confronted a National Guard figure in outrage, only to be warned “Cassocks are not bulletproof.”

In 1977, Romero was appointed as archbishop of San Salvador, a fact that first pleased the government and angered the country’s Marxist leaning priests who hardly saw Romero as an ally. Yet as the country’s poor were subjected to increased violence – and the Church became one of their sole voices – the soft and shy Romero became a seminal figure calling into question the torture of farmworkers, the disappearance of priests who dared to oppose the government, and the thousands who were being murdered for daring to demand respect of their basic human rights.

His voice, which over time literally echoed throughout the country through his radio sermons and messages, would make him the number one target and on March 24, 1980 – at age 62 – an assassin’s bullet would strike him dead in front of altar.

A mere three years after his death, Pope John Paul II visited San Salvador and prayed at Romero’s tomb. Almost immediately following his death, declarations of sainthood rang out throughout the world, yet ongoing debates over whether his death was politically or religiously motivated and deep suspicions within the Vatican of liberation theology, bogged down the formal track to sainthood.

While Romero was not a liberation theologian, his close association with its allies has often been conflated. What is undeniably clear is that Romero was guided by the Church’s preferential option for the poor, leading him to speak colorfully and passionately about the need for the Church to reorient its thinking, finding Christ first and foremost in the life of the poor.

“We must not seek the child Jesus in the pretty figures of our Christmas cribs,” he once wrote. “We must seek him among the undernourished children who have gone to bed at night with nothing to eat, among the poor newsboys who will sleep covered with newspapers in doorways.”

On the eve of his canonization, Archbishop Vicenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, told The Tablet that Romero’s canonization serves as a reminder of Francis’ desire for “a poor Church for the poor.”

“Romero remains a great witness of that love for the poor that is one of the dimensions that comes out from the Second Vatican Council, that Romero lives up to the point of giving his life for the poor, making him virtually the first martyr of the Council,” he said.

After decades of delay, in 2012, it was Pope Benedict XVI who cleared the way for his cause for canonization, noting that he had no doubt that Romero deserved it, and soon after his election in March 2013, Francis fast-tracked the cause.

Last spring, Cardinal José Gregorio Rosa Chávez, Romero’s one-time close friend and current auxiliary bishop of San Salvador, told The Tablet that he believes Romero is the “saint of four popes,” noting that there are elements of his life that shaped or influenced Popes Paul VI, John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis.

“Each one of [the four popes] had a very important part in the process,” he said. “Francis just pushed it forward. Romero is the icon of the Church that Francis wants to be, and the type of pastor he wants.”

When Pope Francis officially declared Romero a saint on Sunday, more than 5,000 El Salvadorans were in St. Peter’s Square to witness the occasion.

Back home on the ground, Catholic Relief Services’ Youth and Migration Advisor in Latin America and the Caribbean, Rick Jones, told Crux that for years El Salvadorans have long considered Romero a saint, “so this only formalizes it.”

Yet for Jones, who is based in El Salvador, still known for having some of the highest homicide rates in the world, he says by lifting up the example of Romero, Francis is providing a moment for the whole country to pause, think about their future, and absorb the “preaching power of non-violence.”

“He’s a beacon of hope and an inspiration in a polarized context,” said Jones. “He allows us to say ‘there is another way.’”

Similarly, for Sister Ana María Pineda, a Sister of Mercy and the author of “Romero & Grande: Companions on the Journey,” she believes that essential to understanding the man who showed a nation – and the world – another way of confronting evil, is to understand a man who allowed his own life and limitations to be radically transformed by closely following God.