When I started writing this monthly column, “Walking With Migrants,” I spoke about the difficulties that religious communities were having with the R-1 Nonimmigrant Religious Worker Visa.

The situation, unfortunately, has gone from bad to worse. Recent changes in the State Department’s interpretation of immigration law will lengthen the time it takes to receive a visa for the vast majority of immigrant religious workers. This especially affects countries where the numerical ceiling for the particular visa relied upon by religious workers was not as much of a factor before the change.

There was already a shortage of visas for religious workers from countries such as Mexico, India, and the Philippines who come to serve in the United States. Numerous religious denominations today make use of this special immigrant visa, known as an employment-based, fourth preference (EB-4) visa. The EB-4 visa category will now have a four-year (or even longer) wait for an application to be approved because this visa category is used by other immigrants, which causes the demand to surpass the approximately 10,000 EB-4 visas available each year. These visas enable these religious organizations to serve their constituents with special language and cultural needs, while at the same time ministering to all their congregants.

The various problems with the nonimmigrant R-1 visas are related to its temporary nature — a two-year initial period and a maximum of five years. Then there is a requirement to leave the country for at least one year before the applicant can return to the U.S. on another R-1 visa. This is certainly an unworkable system by which to ensure consistent pastoral care.

There has been some progress made since the early 1990s when this visa was first instituted by the advocacy work of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Migration and a coalition of other religious groups. I served as staff on the committee during that period. Some progress has been made but the temporary nature still exists in our immigration law. We must continue to advocate for a solution to this need for religious workers that improves both the viability of the R-1 visa and access to the EB-4 visa, which are used by priests, religious sisters, and lay ministers.

In a joint letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, more than 15 major religious organizations recently made helpful suggestions to alleviate some of these problems. If the recent change by the State Department becomes permanent, it considerably hampers these organizations’ missions in society. The USCCB advocates for a delay in implementing the change but seeks ways to secure additional visas for religious workers. Also suggested is an approach to Congress for an increase in the visas allocated to the EB-4 category, as well as lengthening the initial stay for the R-1 visa recipients. The USCCB also addressed the movement from temporary to permanent status which now has become problematic, because of some bureaucratic changes. These are reasonable requests, some of which do not require legislative action.

American communities depend on immigrant religious workers for many services. Of course, these include roles directly related to religious worship within a particular tradition, but many also provide services in place of or in addition to this that are relied upon by the general public. They bring linguistic and cultural competency to roles related to religious instruction, general education, and care for vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, immigrants, refugees, the homeless and hungry, abused and neglected children, and families at risk. Others work in areas as diverse as performing religious outreach, designing and building houses of worship, producing religious publications, sustaining prison ministries, and training health care professionals to provide religiously appropriate health care, as well as religious functionaries who are specially trained in performing specific religious rites and requirements.

In rural and remote regions of the country, immigrant religious workers fill vacancies that would otherwise leave many Americans without access to the means for religious exercise. Moreover, some traditions must rely entirely on the services of immigrant religious workers because they do not have established institutions in the United States to recruit and train the workers they require. Consequently, their presence is vital for us to practice our respective faiths, serve those in need, and respond effectively to the dynamic intercultural realities of modern America.

This situation underlines the need for comprehensive immigration reform, so that our immigration law will serve the common good equitably. Your advocacy with your federal representatives could be of great help in this matter in making them aware of the effect on your own dioceses and parishes. You can contact the Justice for Immigrants organization of the bishops’ conference on their website: justiceforimmigrants.org.

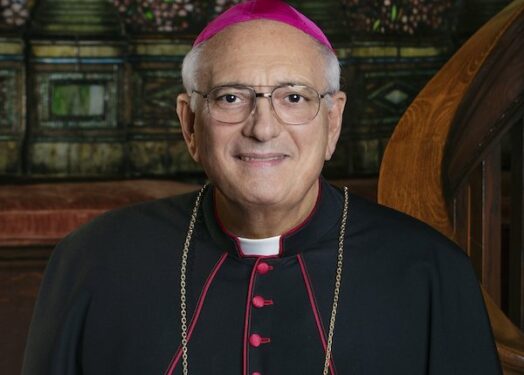

Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio, who served as the seventh bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn, is continuing his research on undocumented migration in the United States.