COLUMBUS, OHIO — The pro-life movement is made up of millions of people dedicated to saving the lives of babies, but in many ways, the story of the fight for the unborn is a story of individuals.

Take Margaret “Peggy” Hartshorn, for instance.

Hartshorn, a Catholic who lives in Columbus, Ohio, is chair of Heartbeat International, an organization founded in Toledo 1971 with a handful of volunteers. It now boasts 100 full-time staff members, operates an Option Line telephone help line and is affiliated with 3,000 pregnancy centers in 80 countries.

In July, Hartshorn was recognized by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops for her many years of advocacy when she was awarded the People of Life Award.

“I always feel very humbled to be picked out for some kind of an award because there are the unsung heroes everywhere in the pro-life movement,” she said.

Hartshorn’s dedication to the pro-life movement stretches back nearly 50 years. It began right after the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, and her work continues to this day.

In 1975, Hartshorn and her husband Mike made the unusual decision to open their Columbus home to young pregnant women, allowing the women to stay with them until they gave birth and got back on their feet. The Hartshorns hosted 12 women — one at a time — between 1975 and 1986.

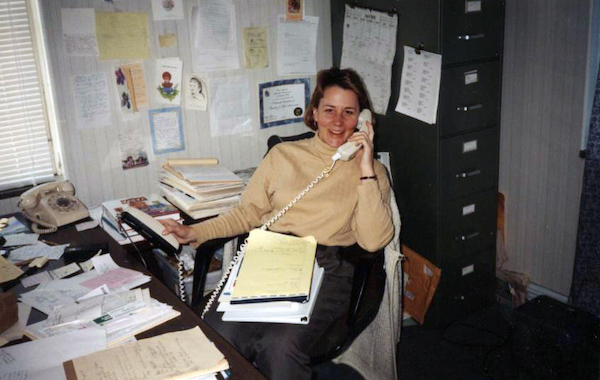

Not only that, but the couple had an extra phone line installed in their home in 1980 and set up a hotline for women to call if they needed help. “I just wanted to be a calm, loving voice on the other end of the phone for scared, pregnant girls,” Hartshorn recalled.

The couple fielded at least 5-10 calls a day for a number of years, directing the callers to resources available to help them.

Through all of her advocacy, Hartshorn enjoyed a professional working life as an English professor at Franklin University. She left that position in 1993 to go to work for Heartbeat International, becoming the organization’s first full-time staff member.

Up to that point, Heartbeat International had been staffed by volunteers. She was soon tapped to serve as president and then eventually became the chair.

Hartshorn traces her political awakening to her time as a college student in the mid-1960s in California, one of the first states in the nation to legalize abortion. “Early in my senior year, billboards started going up, ‘Pregnant? Need Help? Call this number.’ They were advertising abortion clinics,” she said.

Still, while she became politically aware, she did not take immediate action. Instead, she returned to her native Ohio, where she married Mike, her childhood sweetheart, and pursued a master’s degree in education and a Ph.D from Ohio State University.

In January 1973, she was driving to a meeting with her professor to discuss her dissertation when the news came over the car radio that the Supreme Court had issued its Roe v. Wade decision, allowing abortion nationwide.

Hartshorn knew at that moment that she had to get off the sidelines and do something.

She opened her phone book, looked up the number of her local Right to Life office and called it. When the director answered the phone, she told him she wanted to help. “And he said, ‘Well, what do you do now?’ And I said, ‘I’m getting my Ph.D. at Ohio State. And he said, ‘Great. You can be our education director.’ Just like that,” she recalled.

Even though abortion was now legal across the country, many young women who found themselves pregnant chose life for their babies.

However, their choice was not without hardships. Many were rejected by their families, were broke and alone with no place to turn.

After Hartshorn learned of one young woman who was sleeping on an office floor because she had no place to go, she and her husband joined an informal network of homeowners who opened their doors to women in those situations.

“It was just part of being pro-life,” Hartshorn said. “It was people who were willing to say, ‘Okay, I’ll take in that girl facing an emergency in her life.’ Many of these girls were coming from abusive situations.”

Years later, the Hartshorns have kept in touch with many of the women who lived with them back then.

One such young woman, an Irish citizen, who gave up her baby son for adoption shortly after giving birth, returned to her native country. She was reunited with her now-grown son years later. The son invited his birth mother, as well as the Hartshorns, to his wedding.

Another young woman who benefitted from the Hartshorns’ hospitality remained a single mother and stayed in Ohio. Today, her son is a good friend of the Hartshorns’ son Tim. “He is now a small-business owner here in Columbus,” Hartshorn said.

Marveling at the memory, she added, “God has really turned every one of those stories into a very, very positive story.”