By Elise Harris

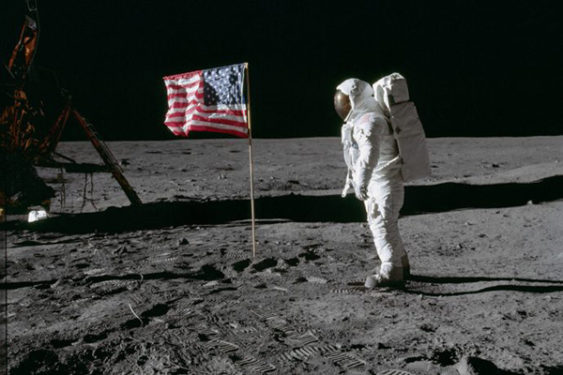

ROME (Crux)— Fifty years ago this month, millions of eyes around the world were glued to the sky as the Apollo 11 spacecraft blasted into orbit, carrying the astronauts who would become the first human beings to set foot on the moon.

Commander Neil Armstrong was the first to step onto the moon’s surface on July 20, 1969, famously describing the event as “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

For many, that event represented not only a climax of scientific accomplishment but was also religious, beckoning a reflection on the divine as humanity seemed to be stretching out its hand and reaching for heaven too.

Crew member Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, who followed Armstrong onto the moon’s surface, carried with him a communion host from his Presbyterian church.

From the earth below, among those watching on live TV was St. Pope Paul VI, who was among various heads of state to send a “goodwill message” into space on a special disc carried by the Apollo 11 crew.

Calling the moon the “pale lamp of our nights and our dreams,” St. Pope Paul VI urged the astronauts to “bring to her, with your living presence, the voice of the spirit, a hymn to God, our Creator and our Father.”

Fast forward to 2019, and the Vatican’s top astronomer, Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory, said the moon landing offers two concrete lessons for people of faith.

Speaking to Crux, he said the first is “hope.”

When U.S. President John F. Kennedy famously declared in 1961 that within the decade, he intended to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth, “the U.S. had not even successfully put a human into orbit,” Consolmagno said. “And yet we did it.”

“The science and technology was astonishing, but even more so was the political ability that got half a million scientists and engineers cooperating together for a common goal,” he said, adding the experience suggests humanity can “face seeming impossible problems if we let ourselves work together.”

Another lesson reminds people that “God is bigger than planet Earth, and that the blue sky overhead is not some sort of boundary between Earth and Heaven,” he said, adding that God created the earth but also the moon and stars “and all the bits we don’t even know enough to imagine yet.”

Along the same lines, Consolmagno said the event bespeaks a compatibility between science and religion, which, although disputed in some circles, is reminiscent of something he once heard from a person working with the poor.

The gist of the phrase, he said, is that “a short-term urge leads to addiction, but a long-term urge leads to purpose.”

“Just as the purpose of space travel let us create something larger than immediate gratifications, so the love of God keeps us directed to a greater purpose, and it lifts us out of the temptations that lead to short-term despair,” he said.

Insisting that there are many points of convergence between science and religion, Consolmagno said that “the joy of discovery is exactly the same as the joy of prayer,” since they both come from the same source, which he said is what author C.S. Lewis famously described as “the source of all Joy that never ceases to surprise us.”

“Why do we do science? For the same reason we ultimately do anything: to know, love, and serve our Creator,” he said.

While Apollo 11 put an end to the 20th-century “Space Race,” in the decades since a new, international outer-space “arms race” has started brewing.

In June 2018 U.S. President Donald Trump announced plans to establish a “Space Force” as the sixth branch of the American military, saying at the time that the decision was not only about the American presence in space, but it was also a bid to boost “jobs and the economy.”

Should Trump follow through, other nations likely would follow suit, evoking fears that Star Wars-like battles could soon be taking place above the earth’s atmosphere.

Noting how the U.S.-USSR Space Race ultimately led to great scientific and technological accomplishment, Consolmagno said there is “a wonderful benefit to competition,” and he sees it as a positive step that nations and, increasingly, private corporations, are learning how to live and work in space.

Yet he also said there’s need for a set of common rules governing space activity “just so that we don’t get in each other’s way.” He sees the United Nations’ Office of Outer Space Affairs as the natural place for these rules to be worked out.

In 2018 Consolmagno represented the Holy See at a meeting for that office in Vienna, marking the 50th anniversary of the 1967 U.N. “Outer Space Treaty” on governing the activities of states in outer space.

He cautioned that wherever human beings go, “our flawed nature will also go; there’s no getting around that.” On the other hand, he also insisted that “where human beings go, the image and likeness of our Creator also goes.”

“We cannot expect a paradise in space; we lost Paradise, many years ago. But we can also find new and wonderful places to encounter God,” he said.

If humanity is capable of harnessing the same creativity, determination and collaboration that allowed Apollo 11 to happen, many modern crises, he said, citing climate change as an example, “can be met if we have the will.”