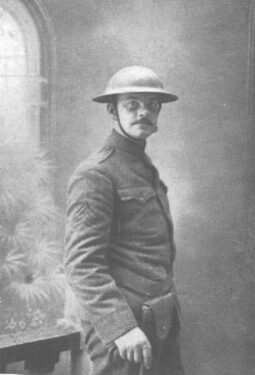

PROSPECT HEIGHTS — Alfred Joyce Kilmer, a celebrated poet in the early 1900s, didn’t have to fight in France during World War I, but he did.

When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, he was 30, an accomplished journalist, book editor, literary critic, and lecturer. He was married and the father of five children, including a 5-year-old daughter paralyzed from polio. In 1913 he converted to Catholicism.

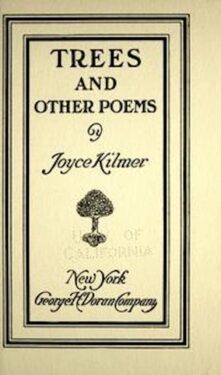

Kilmer, who usually went by his middle name “Joyce,” was most famous for writing verse, like his poem “Trees.” It’s the one that starts with:

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree …

Father Francis Duffy, the famed chaplain of the 69th Infantry Brigade of the New York National Guard, wrote of befriending Kilmer. The poet was assigned to the 7th Infantry Brigade, but he asked the chaplain’s help to arrange a transfer to the 69th.

In “Father Duffy’s Story,” the chaplain wrote that if it was up to him, he would’ve made Kilmer “stay home and look after his large family and let men of fewer responsibilities undertake this task.

“But,” Father Duffy added, “he is bound to do his share and do it at once. He is going about this thing in exactly the same manner that led him to enter the Church.”

Neither Irish nor Catholic

Kilmer began life neither Irish nor Catholic.

He was born in 1886 to a family of English heritage in New Brunswick, New Jersey — the youngest of four children.

His father, Dr. Frederick Kilmer, was a pharmacist who worked for Johnson and Johnson Company, for which he invented Johnson’s Baby Powder. He and his wife, Annie, raised their children in the Episcopal Church.

Kilmer attended Rutgers College (now a university) but transferred in 1904 to Columbia University in New York City. After graduating in 1908, he married Aline Murray. They were engaged during his sophomore year at Rutgers.

In the city, Kilmer worked for the reference book publishing firm Funk & Wagnalls. He spent three years writing word definitions in the company’s 1912 edition of The Standard Dictionary.

Around this time, Kilmer began his career in poetry. “Summer of Love,” his first book of verse, appeared in 1911.

He wrote “Trees” in 1913 and it was published in a poetry magazine a year later.

Easy to Recite

Lee Ann Brown, an English professor who teaches creative writing and poetry at St. John’s University, said Kilmer “is very much part of that ‘parlor culture’ of American poetry when everyone entertained themselves by playing the piano, singing songs, and reciting poetry in their living rooms.

“People would have these big fireside ‘readers’ — anthologies that were full of poetry that was rhythmic and musical, easy to recite. And people would do it from memory.”

“Trees” is an example of that kind of poetry, Brown said.

Kilmer’s Roman Catholic faith inspired his poetry in celebrating the beauty of creation and the natural world. Literary critics in the 1920s considered him the preeminent Catholic poet in the U.S.

Brown noted, however, that Kilmer’s poetry has “fallen a little bit out of fashion.

“It’s a little bit of a cliché,” she explained, “because it’s so rhythmic, so sentimental. It’s typical nature poetry, but it sort of represents an old-fashioned view of human beings being separate from nature — looking at it and saying this is a beautiful thing to appreciate.

“Nowadays, people, when they write about nature, usually think of what’s called ‘eco poetics’ where we say we are ‘part of’ nature.

“But I want to be an advocate for poetry, no matter what. And, of course, ‘Trees’ was one of the most popular poems in American memory that people choose to memorize.”

Kilmer authored four more books before joining the military, including, “The Circus and Other Essays” (1916), a series of interviews with other writers, “Literature in the Making” (1917), “Main Street and Other Poems” (1917), and “Dreams and Images: An Anthology of Catholic Poets” (1917).

Beautiful Paths

Kilmer’s spirituality veered toward Catholicism in 1912 with the birth of his daughter, Rose. She was paralyzed with poliomyelitis (polio). Kilmer and his wife became Catholic a year later.

In letters, Kilmer explained that for a long time, he “believed in the Catholic position, the Catholic view of ethics, and aesthetics.” He also sought “something not intellectual.”

“In fact,” he wrote, “I wanted faith. It came, I think, by way of my little paralyzed daughter. Her lifeless hands led me; I think her tiny feet know beautiful paths.” Rose died in 1917 before Kilmer went to France.

Affinity for the Irish

Kilmer’s zeal to join the 69th was rooted in notions of tradition, honor, and faith, said writer Séamus Ó Fianghusa (Fennessy), who is working on a book about the brigade.

He is the author of “Heaven Help Us, Now!: A Self Help Guide to God’s Own First Responder, St. Jude Thaddeus.” He is a staff sergeant who served 10 years with the 69th and also deployed to Afghanistan with the Vermont National Guard.

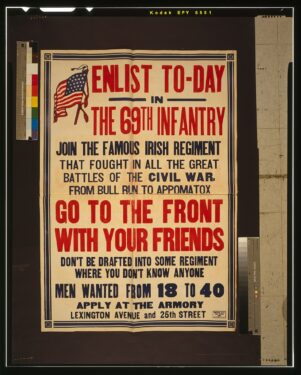

Ó Fianghusa described how the 69th was founded as a regiment in 1849 by Irish immigrants who came to New York City in the aftermath of the Great Famine.

“As an American military unit, they really made their claim to fame in the American Civil War,” he said. “They fought in such numbers, and with such a passion, and with such bravery throughout all four years of the war, that they (became) Americans in the eyes of everyone.”

Ó Fianghusa added that the pervasive anti-Irish and anti-Catholic discrimination of that era didn’t disappear overnight. Still, the 69th’s battle record “went a long way to making Irish Catholics accepted.

“So,” he continued, “by the time of the First World War, the 69th already had an established reputation. But it seems that once Joyce Kilmer came into the faith, he found a natural affinity for Irish people. When he converted, it seemed like the ethnic identity went with it.”

Father Duffy successfully arranged the transfer. In November 1917, they arrived with the regiment in France.

A Regular Dude

The Army renamed the 69th as the 165th Infantry Regiment and attached it to the 42nd Infantry “Rainbow” Division. Still, most soldiers knew the 165th was the old 69th and kept calling it that in both world wars, Ó Fianghusa said.

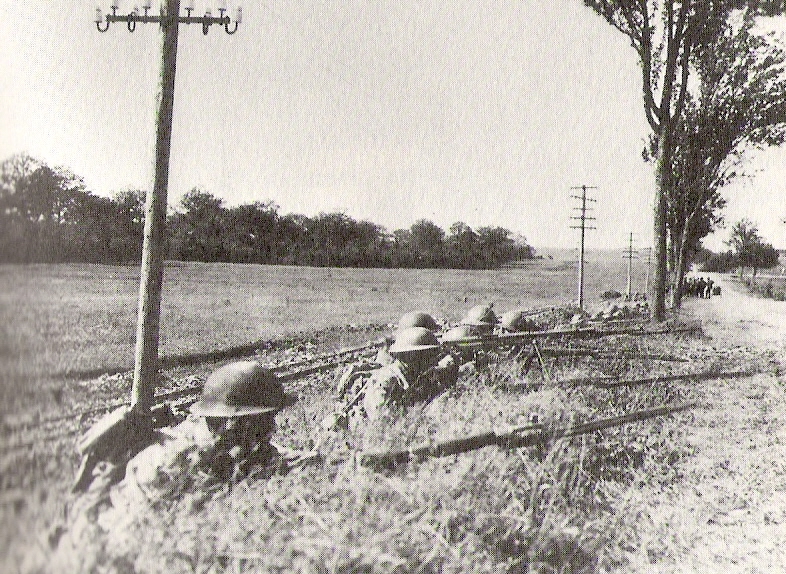

The regiment moved toward the fighting in the spring of 1918. The troops occupied a supposedly “quiet” sector near Baccarat when German artillery destroyed a shelter containing two dozen of New Yorkers; 19 died, and 14 of them were entombed in the destruction.

Kilmer honored those men with his poem “Rouge Bouquet.” These 55 lines begin:

In a woods they call the Rouge Bouquet

There is a new-made grave today,

Built by never a spade nor pick,

Yet covered with earth ten meters thick.

There lie many fighting men,

Dead in their youthful prime,

Never to laugh nor love again

Or taste of the Summertime …

Kilmer advanced in rank from private to sergeant in charge of reconnaissance scouts.

“He was more than qualified to be a commissioned officer,” Ó Fianghusa said. “But he wanted to serve as just a soldier. He was considered just a regular dude, even though, in one sense, he was a high-society fella from a privileged background.

“The intellectual types would chat with him about literature into the late hours. But the rough Irish longshoremen loved him. He was a brave fellow. He wasn’t afraid to get dirty.”

Dear and Gallant Soul

On July 30, 1918, Kilmer led his squad beside the Ourcq River near the village of Seringes-et-Nesles. Their mission was to find a German machine gun nest, but a sniper found him first.

“A bullet had pierced his brain,” Father Duffy wrote. “His body was carried in and buried by the side of [Lt.] Ames. God rest this dear and gallant soul.”

Numerous tributes honored Kilmer’s memory, including a plaque in Central Park and the Sgt. Joyce Kilmer Triangle just off Kings Highway in the Midwood neighborhood of Brooklyn. Joyce Kilmer Park is near Yankee Stadium, and the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest is part of the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina.

In the preface of his memoir, Father Duffy noted that Kilmer had agreed to write the book and completed a portion of it, but “I took over the task after his death in battle.

“The manuscript he left had been hurriedly written, at intervals in a busy soldier’s existence, which interested him far more than literary work,” Father Duffy wrote.

“I have taken the liberty,” he continued, “of adding his work, incomplete though it is, to my own; because I feel that Kilmer would be glad at having his name associated with the story of the Regiment, which had his absolute devotion; and because I cannot resist the temptation of associating with my own the name of one of the noblest specimens of humanity that has existed in our times.”

What a great article. I enjoyed learning so much about the poet. I remember in grammar school singing his poem “The Tree”. I had the privilege of finding Joyce Kilmer’s grave in the Oisne-Aisne WWI American Cemetery in France in 1978.. I was told by the caretaker that he was buried just 500 yards from where he was killed by the sniper. I am a member of Alpha Phi Delta National Italian Heritage Fraternity and we have a Chapter in Rutgers University where Joyce Kilmer Hall stands. When I took the photo of Joyce Kilmer’s grave I sent a copy a copy to the Governor of New Jersey, Rutgers Univesity and the NJ Turnpike Authority since they had a rest stop named after Kilmer.