PROSPECT HEIGHTS — They were Catholic religious women, dedicated to educating children, treating the sick and helping the poor and enslaved in pre-Civil War America.

But when they attempted to enter and live in convents, they were turned away — because they were black.

In the years when slavery was still legal, black Catholic women shunned by white convents did what they felt they had to do: they founded their own religious orders.

The first religious order to accept black women was the Oblate Sisters of Providence, a community of nuns founded in Baltimore in 1828 by Mary Elizabeth Lange. Former slaves who had been freed were among those joining the order.

Lange (1784-1882), who became known as Mother Mary Lange, guided the sisters to another first: establishing St. Frances Academy, the first Catholic school to accept black children.

More than a pioneer, Mother Mary Lange could be on her way to sainthood. A cause for her canonization was opened in 2004 and the Church has bestowed on her the title of Servant of God.

However, while Mother Mary Lange is an important figure in the history of black sisters, it’s possible she was not the first.

Black women were accepted into religious communities before 1828 — but only because they passed themselves off as white, according to Dr. Shannen Dee Williams, associate professor of history at the University of Dayton and author of the book, “Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle.”

“Long before they were black priests in this country, there were black sisters,” Williams added.

In 1824, a small group of women in Kentucky organized a black auxiliary to an existing religious order, the Sisters of Loretto at the Foot of the Cross. The auxiliary members took vows, but worked separately from their white counterparts, even wearing different habits.

Their good works were short-lived. “These women were released back into the world due to, as one historian said, the bishop at the time suggesting that the time was too premature for colored nuns,” Williams said.

As a consequence, their individual identities are lost to history. “We do not know those women’s names,” Williams said.

Nine years after the formation of the Oblate Sisters, the second black religious order was established — the Congregation of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary — founded in New Orleans in 1837.

Their founder was Henriette DeLille (1813-1862), a Creole-American woman who led a small group composed of seven Creoles and one French woman. The religious order changed its name to Sisters of the Holy Family in 1842.

“These first congregations of religious black sisters did tremendous work. But one must remember the reason these congregations were formed. They were not allowed into white congregations,” said Msgr. Paul Jervis, pastor of St. Francis of Assisi-St. Blaise Parish in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, Brooklyn.

Msgr. Jervis spearheaded the initial effort for the canonization of Msgr. Bernard Quinn, founder of St. Peter Claver Church, the first black Catholic Church in the Diocese of Brooklyn.

In their efforts to help the needy, the Sisters of the Holy Family were met with racism, even from within the Catholic Church. For example, their bishop prohibited the sisters from wearing habits. They were not permitted to wear habits until 1876 — nearly 40 years after they were founded.

But Mother Henriette and her members found ways to buck authority. In 1850, they founded a school and taught slaves at a time when such a practice was illegal.

Among their other accomplishments: they also founded the Hospice of the Holy Family (now known as Lafon Nursing Facility) in New Orleans, the oldest Catholic nursing home in the U.S.

Mother Henriette, like Mother Mary Lange, is perhaps on her way to sainthood. The cause for canonization was opened in 1988. In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI declared her to be Venerable.

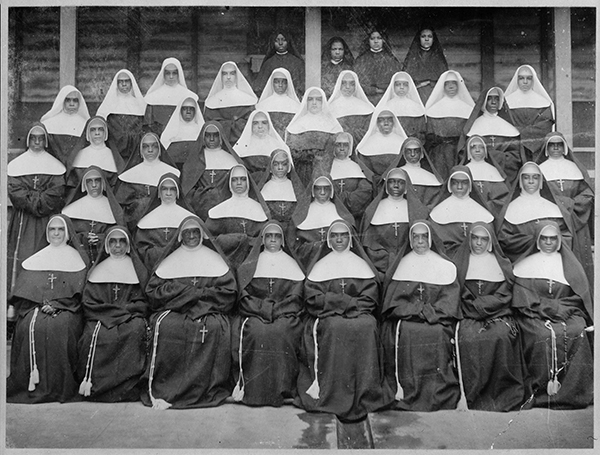

The Oblate Sisters of Providence and the Sisters of the Holy Family started a tradition of service by black Catholic religious women in the U.S. Both religious orders are still in existence today.

For many years, the traditionally black religious orders were the only place to turn for black women seeking to live a consecrated life — the scourge of segregation remained in place into the mid-20th century.

“The only communities willing to accept women of African descent were the African-American orders,” Williams noted. “There were some exceptions that were made, particularly for black women who were racially ambiguous and who are allowed to enter white communities. But those barriers did not begin to fall until after World War II.”

Illuminating. All of this history was unfamiliar to me. Excellent kickoff for Black History Month.I think many white Catholics in the Diocese are quite prejudiced, so I hope they’ll read articles like this.