BEDFORD-STUYVESANT — It’s a short stroll from Violet Chandler’s home on Jefferson Avenue to St. Peter Claver Church, which is the lifelong spiritual home for this 71-year-old retiree.

The church’s pastor, Father Alonzo Cox, does not live at St. Peter Claver, so he often relies on Chandler to be a go-to volunteer. Although she doesn’t hold a specific title, she has a lengthy list of things to do.

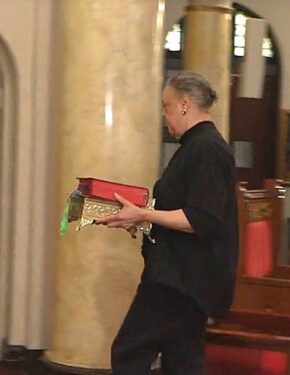

Most days, Chandler enters with her own set of keys. She awakens the church, flipping fuse-box switches, and preparing the Bible, the sacramentals, and sacred vessels for Mass.

RELATED: Trailblazing Teacher Pioneered Diversity in New York Catholic Schools

“She’s the backbone here,” Father Cox said. “She volunteers here with opening the church and setting up for Mass. She also volunteers as an altar server and an acolyte for Mass.”

Other tasks include sexton, sacristan, and collecting mail.

Often working behind the scenes, she ensures everything runs smoothly, including special events like the annual blessing of the animals.

“She does it all,” Father Cox said. “Violet is the jack of all trades.”

To which, she replied: “But a master of none!”

Still, despite that burst of humility, Chandler also mentioned that she once rigged up a sump pump to keep water from rising in the basement.

“So,” she added, “I guess we can add plumber.”

Chandler, who grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, retired as a lawyer nearly four years ago. But these days, with her own children grown and a grandchild on the way, she is busier than ever volunteering at the historic church.

In the 1920s, St. Peter Claver Church became the first real home for black Catholics in the Diocese of Brooklyn — thanks to the persistent efforts of Msgr. Bernard Quinn, now a candidate for sainthood.

Although segregation once defined the southern United States, black people in the north still faced bigotry, as evidenced by Msgr. Quinn’s struggles to develop a church for Black Catholics.

“In Brooklyn, there were a number of Catholic churches in close proximity,” Chandler said. “But black people were just not welcomed.”

Chandler recalled discussions with people who assumed black people in northern states were free of the same mistreatment faced by African Americans in the south, to which she would reply, “You want to bet?”

Chandler related how, as a child, her older sister and some friends arrived too late for confession at St. Peter Claver, so they went to a nearby Catholic church.

RELATED: Keys to the Past: How Brooklyn Church’s Pipe Organ Bridges Faith, History

“The pastor at the time came out and told them, ‘Go back to your … church. And don’t put your hands in the holy water [on your way out],’ ” Chandler said. “Fast forward 20 years, and who do you suppose they made pastor of [St. Peter Claver]? It was the same guy who ran them out.

“God has a sense of humor.”

Chandler noted that once Msgr. Quinn got permission to start the church, he set out to make it a welcoming place for people of all backgrounds.

“That wasn’t what we felt when we were kids in other parishes,” Chandler said. “But now we just quietly go about welcoming other Catholics into our parish. I mean, if any person of any color walks into the parishes, it’s universal.

“You’re welcome here.”

Chandler said she volunteers at the church to keep it going so that its historical legacy can be built upon and not forgotten.

“Talk is cheap,” she said. “But the most important thing that I can do is to be an example to recruit the next generation.”

Additional reporting by Christine Persichette, Currents News.

THANK YOU FOR KEEPING OUR STORY, CATHOLICS OF AFRICAN DESCENT, CURRENT AND NOT JUST AN HISTORICAL EVENT. The video and print pieces in this edition were impeccably written and crafted. Barbara McFadden