“Those cart loads of old charnel ashes, scales and splints of mouldy bones,

Once living men — once resolute courage, aspiration, strength,

The stepping stones to thee to-day and here, America.”

— Walt Whitman, “The Wallabout Martyrs”

FORT GREENE — Dog walkers, fitness buffs, and a wedding party swarmed about the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument at Fort Greene Park one recent weekend afternoon, perhaps unaware that entombed beneath them lay thousands of American prisoners from the Revolutionary War.

Meanwhile, nearby, a small group of people gathered at the base of the monument to honor the dead from that bygone war, in the 113th annual memorial tribute sponsored by the Society of Old Brooklynites.

The Aug. 28 event also commemorated the 245th anniversary of the Battle of Brooklyn (Aug. 26-30, 1776), the first major clash — and the largest of the war — since the colonists declared their independence on July 4.

“This is sacred ground,” Brooklyn Parks Commissioner Martin Maher told the audience. “So few people know the story of this.”

Yet, he added, the crypt beneath the monument holds the remains of an estimated 11,500 prisoners, contained in 20 large stone caskets.

“And just to put that in perspective,” Maher said, “in the entire American Revolution, from 1775 to 1783, from Georgia to Massachusetts, roughly 8,500 were killed in combat. Yet, right here in Brooklyn are buried 11,500 patriots who perished in the cause of liberty.

“On a daily basis, they were given the opportunity to renounce the patriot cause and to join with the British Navy. In history, there is not one recorded instance of that happening,” he said.

‘What Brave Fellows’

After spending much of 1775 besieged by colonists at Boston, the British pulled out to retrofit, resupply, and reinforce their army. Then in August 1776, the force invaded New York via Staten Island, and then Long Island, intending to open a new front and, ultimately, crush the insurrection.

The first shots of the Battle of Brooklyn crackled in a brief skirmish around 10 p.m. on Aug. 26; fighting intensified after sunrise the following day.

The British outnumbered and outmaneuvered the Continental Army commanded by Gen. George Washington. He watched the fighting from Cobble Hill, near present-day Court Street and Atlantic Avenue (near the Trader Joe’s market).

From there, the future first President saw a unit later dubbed the “Maryland 400” attack the British at the Old Stone House (located today on 3rd Street near 5th Avenue) near Gowanus Creek. The Marylanders lost the fight and 256 men. Washington reportedly uttered, “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose.”

Although Washington lost the battle, he did manage to evacuate remnants of his army across the East River to Manhattan, able to fight another day. After more setbacks, the Continental Army would turn the tide against the British and finally win independence.

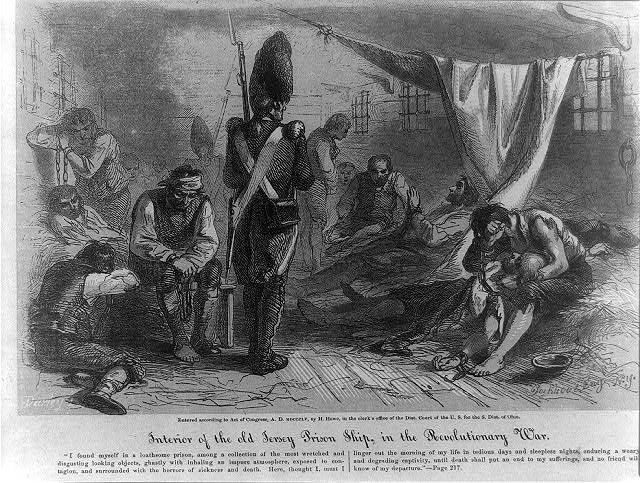

But first, 1,000 prisoners from the Battle of Brooklyn were incarcerated on vessels considered no longer seaworthy and thus repurposed as “prison ships.” Thousands more would join them, including some women, until the war’s end in 1783. Thousands would die of starvation or disease.

The British moored 22 prison ships around Long Island. Many, including the infamous HMS Jersey, anchored in Wallabout Bay near the present-day Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“You were basically condemned to death if you were going to be on one of these,” Maher said. “There were very few survivors that could tell the story.”

The book “American Prisoners of the Revolution” by Danske Dandridge contains a note from escapee Robert Sheffield of Connecticut. About his fellow prisoners, Sheffield

wrote:

“Their sickly countenances, and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some swearing and blaspheming; others crying, praying, and wringing their hands; and stalking about like ghosts; others delirious, raving, and storming — all panting for breath; some dead, and corrupting. The air was so foul that at times a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which the bodies were not missed until they had been dead ten days.”

‘In the Wallabout Sands”

Ted General, first vice president of the Society of Old Brooklynites, said prisoners who died were “tossed” overboard or buried in shallow graves “on the edge of Wallabout Bay.”

“And then, as the water washed the sand away, it exposed the remains — the skeleton bodies that were there,” General said.

The estimate of 11,500 prisoners comes from ship manifests, but not all vessels kept such records. The HMS Jersey, alone, however, noted 8,000 deaths, General said.In 1808, the remains were gathered and placed in a tomb near the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

By the mid-1800s, a city park was developed on high ground that once held Fort Greene. Included was a crypt for the martyrs because the original tomb fell into disrepair.

The park, eventually named for the fort, was funded by Walt Whitman, then an editor for The Brooklyn Eagle and renowned as one of America’s greatest poets.

In the introduction to his poem, “The Wallabout Martyrs,” Whitman wrote:

“In Brooklyn, in an old vault, mark’d by no special recognition, lie huddled at this moment the undoubtedly authentic remains of the staunchest and earliest revolutionary patriots from the British prison ships and prisons of the times of 1776–83, in and around New York, and from all over Long Island; originally buried — many thousands of them — in trenches in the Wallabout sands.”

‘We Know of Your Hardships’

The towering Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument atop the crypt was dedicated in 1908 by President-elect William Howard Taft, at a ceremony that drew an estimated 15,000 people.

By contrast, about two dozen people attended the memorial tribute on Aug. 28.

“This is our signature event,” said General, who belongs to St. Patrick’s Parish in Bay Ridge. “One of the things that we attempt to do is give some civic awareness.”

General gave a brief tour of the outside of the crypt.

“Years ago,” he recalled, “I was in there with a couple of congressmen and the adjutant general for the state militia. They had the top of one of the slate boxes open, and you could see some of the bones.

“Most people — like those up there exercising, doing yoga — they don’t have a clue what this is all about.”

During the Aug. 28 tribute, Emma Andre of Young Dancers in Repertory performed an interpretive dance. Also, Daniel Sutin, a baritone with the Martha Cardona Opera Company, sang several patriotic songs.

A “piping ceremony” was conducted by Michael Spinner, master of ceremonies and second vice president of the Old Brooklynites.

In this tradition, a bosun’s pipe is sounded and the speaker addresses the martyrs below in the crypt. Then, the speaker urges them to “muster on the quarterdeck so you could receive the honor that you will deserve and never received.”

“Do you hear me down there?” Spinner recited. “We know of your hardships, your sickness, your disease, your pestilence, starvation, hypothermia, and inhuman treatment by the British during your incarceration aboard these prison ships anchored in Wallabout Bay.

“We have not forgotten you.”