HILLCREST — “You foolish men,” begins a poem by one of Mexico’s most renowned writers. With the reader’s attention firmly in her grip, she chastises men who:

“lay the guilt on women,

not seeing you’re the cause

of the very thing you blame;

if you invite their disdain

with measureless desire

why wish they will behave

if you incite to ill.

You fight their stubbornness,

then, weightily,

you say it was their lightness

when it was your guile.”

— From “Foolish Men” by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

The poem continues in many verses. In them, the writer’s tone echoes modern-day feminism, yet she penned these words in the 17th century — hundreds of years before waves of women’s movements made their own marks around the world.

And she was a nun living a cloistered life in Mexico.

Still, Sor (Sister) Juana Inés de la Cruz is celebrated as a literary giant far beyond her homeland, where she was born in 1648 near Mexico City. She also wrote dramas, comedies, music, and treatises on mathematics and philosophy.

Such feats were unheard of then because women were banned from pursuing higher education in Spain’s colonial holdings. Even her mother was illiterate, said Alina Camacho-Gingerich, a professor and chair of the Department of Languages and Literatures at St. John’s University.

“She really was a genius in every sense of the word,” Camacho said of Sor Juana. “She was also a great defender of women’s rights, and probably the first feminist in the New World.”

Juana’s quest for knowledge faced numerous barriers.

Her mother was the daughter of a wealthy landowner from Spain, but Juana was born out of wedlock. Her father was a Spanish military officer who chose not to be involved with the family.

Juana’s grandfather, however, made a home for his daughter and three granddaughters on his property in San Miguel Nepantla, New Spain (Mexico).

He had an extensive library where Juana resolved to become self-educated. The child could read and write Latin by age 3. Two years later, she gained enough mathematical acumen to do accounting. When she was 8, she wrote a poem about the Eucharist.

Juana also taught herself the Aztec language, Nahuatl, and used it to write a couple of poems.

“Obviously, it was a gift from God,” Camacho said. “Her parents definitely were not intellectuals. They could have been naturally intelligent, but we don’t know.

“So she was blessed with that intelligence.”

Later, Juana learned that girls were not allowed to pursue higher education. Outraged, she planned to disguise herself as a male student, but her mother said no. Still, the child’s intellect grew.

At age 16, she went to Mexico City to be a lady-in-waiting for a viceroy of the royal court and his wife. She entertained the court with her plays and poems of romantic love. Her reputation for having a towering intellect also gained traction.

Another viceroy invited a cadre of jurists, philosophers, poets, and theologians visiting from Spain to test the 17-year-old girl’s knowledge. She correctly answered each question put before her.

“She would astound the men of the court with her knowledge — a woman who had no access to formal education,” Camacho said.

About this time, her poem “Hombres Necios” (“Foolish Men”) took a swipe at the patriarchal society of the time. In particular, the poem singled out men who perpetrated sexist double standards by claiming some women were morally corrupt while turning a blind eye to their own sexual indiscretions.

Despite the controversy, Juana was pursued by several suitors, but she declined marriage, fearing it could quench her thirst for knowledge.

Instead, she chose the religious life because it gave her the freedom to study. She began as a novice with the Carmelite sisters.

By age 20, she settled into the Hieronymite convent of Santa Paula, where she took the new name, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. There, she spent the rest of her life as a cloistered nun. She also became the treasurer and archivist for the community, and she kept writing.

Meanwhile, she amassed her own library and received visits from prominent scholars. Religious life, however, did not quell her outspokenness.

In 1690, a bishop published Sor Juana’s private critique of a homily without her permission. Church leaders scolded her and insisted that she devote herself to prayer, not debate.

Camacho said Sor Juana’s response came in the form of an autobiographical letter.

“In it, she talks about her life and how, since she was a very young child, she would read and devour books,” Camacho said. “She explained how she would discipline herself.

“If she did not meet her quota of books, she would cut her hair. And of course, this was an incredibly important symbol for women of 17th-century New Spain.”

Sor Juana also declared that God would not have given women intellect if he did not want them to use it, Camacho said.

But, the professor said, Sor Juana’s knowledge of science, math, and philosophy enabled her to better understand God’s creation and His holy Scriptures and to share them with the world.

“She needed to read as much as possible from all the disciplines in order to do justice to the sacred text, which is the Bible,” Camacho said. “She said, ‘I felt the need to know as much as I could, from all the disciplines available to me, to better understand my faith, the sacred word.’

“I thought that was an incredibly smart answer.”

The Church, Camacho explained, was the center of everyone’s life.

“In her defense, she comes out very clearly on the need for higher education for all women,” Camacho said.

Ultimately, however, Sor Juana signed a document promising to stop writing. But she signed it, “I, the Worst of All,” and with her own blood.

Camacho said it is a matter of speculation exactly what Sor Juana was trying to communicate with that dramatic action.

“We don’t know if that was true repentance,” Camacho said. “Did she feel the need to repent for her intellectual curiosity and for her readings and writings that were not sacred? Was it the weight of the criticism that accumulated throughout the years? We hope not.”

Still, Camacho said she is confident that Sor Juana’s choice to disengage with intellectual discourse was indeed proof of her humility. She spent her final years nursing sisters stricken with disease before becoming ill and dying at age 47.

“What is clear to me is that she was also blessed with tremendous intelligence and an inquisitive mind,” Camacho said. “Most of her life, she did not find a dichotomy between one or the other.

“She was very sincere in her desire to serve God. There’s no question in my mind about that. She very much loved God.” WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH

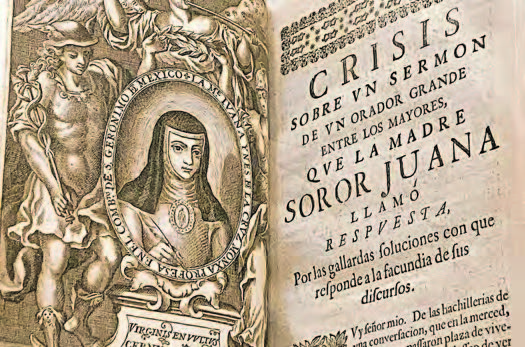

Top: Famed artist Miguel Cabrera made this painting of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. He was born the same year the poet-nun died — 1695. Bottom: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s signature (Photos: Wikimedia Commons)