SPRINGFIELD GARDENS — People of the Nigerian diaspora in the Diocese of Brooklyn had hoped the national election back home in February would bring a new president, serious about quelling anti-Christian violence.

These local Nigerian Catholics had urged friends and family to support an opposition candidate, Peter Obi. They believed he would have put a stop to the persecution of Christians. The diaspora was optimistic because Obi, a businessman, had galvanized support among young adults who were registering to vote at record levels.

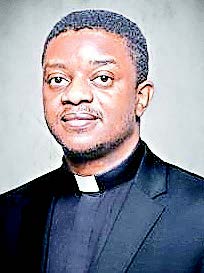

But their hopes “were dashed,” said Father Cosmas Nzeabalu, coordinator of the Nigerian Apostolate for the diocese. Nigeria’s ruling party candidate, Bola Tinubu, claimed victory amid widespread accusations of election fraud, plus renewed violence against Christians at the polls.

Father Nzeablu also serves as parochial vicar for St. Mary Magdalene Parish in Springfield Gardens. He said he believes the election was “rigged.”

“A very high organizing committee, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) gave the people hope that the election would be fair,” he said. “But what happened, after all, was Tinubu was alleged to have bribed INEC.

“So that brought about ballot snatching and ballot box destruction. Many people were killed. So many people were wounded.”

An attendant refugee crisis forced scores of people to flee the violence. They go to camps set up for internally displaced people (IDPs). Some people move from camp to camp to avoid violence.

Monitoring the chaos is the Denis Hurley Peace Institute, named after South African Catholic Archbishop Denis Eugene Hurley, who is based in Pretoria, South Africa. It theorizes that the election results have emboldened armed Fulani-speaking herdsmen to attack Christians. The institute has called this danger a “gathering storm.”

Meanwhile, recent attacks in the Benue and Ondo States show that the Fulanis are targeting areas well to the south of the disputed “Middle Belt” region, where the Muslim herdsmen have clashed with Christian farmers over control of fertile croplands.

The southern push is to be expected, said Ed Clancy, evangelization and outreach director for Brooklyn-based Aid to the Church in Need-U.S. Clancy said this prediction was made in 2018 by Bishop Jude Ayodeji Arogundade of the Diocese of Ondo.

“He came to talk to us in Brooklyn, and he said the Fulani are on the verge of changing the dynamics of this conflict,” Clancy said. “It’s not a farmer-herder conflict. It is about the takeover of territory and control. He said people will realize that it’s not just up in the north or the Middle Belt where the Fulani are moving their herds. Well, it happened.”

Bishop Arogundade had previously served Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish in Elmsford, a village in Westchester County, before returning to Nigeria to become bishop of Ondo.

Taking his place at the Elmsford parish is Father Augustine Dada, also from Ondo. Father Dada, an assistant pastor, said he is there to serve the children of God. But he also has a second mission: to be a contact in the U.S. for people who want to reach Bishop Arogundade to offer help to Catholics in Nigeria.

He said the violence in Nigeria struck close to home on June 5 of last year when Fulani gunmen attacked St. Francis Catholic Church in Owo, in Ondo State. The congregation had reached the end of the Mass celebrating the feast of Pentecost when the attackers unloaded deadly gunfire, followed by a few sticks of dynamite, killing 50 people.

Father Dada was at the parish in Elmsford when images of the Owo massacre surfaced on social media.

“At first, I didn’t know this was in my diocese,” he said. “Then I got a text message notifying what just happened. Immediately I called the bishop, but he was right in the middle of responding to the massacre. He told me that he was going to talk to me later.”

Father Dada said it was a sad day when “armed men came down into my Diocese of Ondo, in the south of Nigeria, which is relatively peaceful.

“I know the priest who was celebrating that Mass,” Father Dada said. “(He) used to be a seminarian who worked with me when I was still in Nigeria. Those who died are all known personally to me.”

This type of violence accelerated in the days before and after the election in February. For example, on Jan. 19, a priest in northern Nigeria died in his rectory, which was set ablaze by attackers.

Clearly, Father Dada said, the targets are Christians, but also some Muslims who don’t ascribe to the attackers’ theology. Still, the violence has no justification and must be declared as criminal and dealt with accordingly, he said.

But, while the diaspora’s hopes fell with the election results, local Nigerians aren’t giving up hope. Father Nzeabalu noted that a Nigerian court will examine whether the election was rigged. If that ruling is not favorable, plaintiffs can appeal it in Nigeria’s supreme court.

Meanwhile, Clancy joins Fathers Nzeabalu and Dada in urging prayers for Nigeria and persecuted Christians there.

“It’s not a done deal,” Father Nzeabalu said of the election. “We are people of faith, and we’re all praying that Nigeria will have justice and that the right person will become president to better the lives of the people.”