LITTLE ITALY — Ascending to an upper floor of the Italian American Museum’s new building on Mulberry Street brings one face-to-face with the heroes and villains of epic poetry from the Great Renaissance.

Lining the walls are dozens of brightly painted life-size wooden figures — marionettes — most notably Orlando, the chief paladin (or knight) of King Charlemagne. The characters include the treacherous Count Gano, the demonic Nucalone in head-to-toe red, pagan captains, giants, clowns, the fetching Fulbia, and Charlemagne himself.

These marionettes, crafted 100 years ago, dazzled audiences in Little Italy under the direction of master puppeteer Agrippino Manteo from 1923 until 1939.

Now, thanks to his family, “Papa Manteo’s Marionettes” have a new home in the Italian American Museum (IAM) at 151 Mulberry Street — a short walk from its longtime venue at 109 Mulberry.

“This is a tribute to a Sicilian family, the Manteo family, who came here in the early part of the 20th century,” said Joseph Scelsa, IAM’s founder and president. “They had a puppet theater, and they would perform stories, like ‘Orlando Furioso.’”

Scelsa said the acquisition dates back to the 1980s when he befriended Agrippino’s son, Michael, a second-generation puppeteer, who struggled to find suitable storage for the retired marionettes.

“He was looking for one spot,” Scelsa said. “I said, ‘Well, you know, I’m going to build a museum.’ So, he gave me all the puppets that they had left in their collection. I made the promise that I would bring them back to Mulberry Street.

“And that’s why they’re here today.”

Agrippino was born in 1884 in Grammichele, Sicily. Orphaned as a boy, he went to live on his grandmother’s farm but often ran away to escape harsh child labor. Around that time, he discovered “Opera dei Pupi” (opera of the puppets) — an art form that proliferated since the early 1800s in Sicily,

It was “love at first sight,” said Jo Ann Cavallo, author of “The Sicilian Puppet Theater of Agrippino Manteo: The Paladins of France in America.”

Cavallo, who is chair of the Italian Department at Columbia University, described how Agrippino was fascinated by the workings of the ornate, life-size puppets and went backstage to learn more. By age 17, he was an apprentice to his mentor, the renowned puppeteer Giuseppe Crimi.

“The cultural scene at the time was one in which puppet theater was alive, creative, and on par with dramatic theater,” Cavallo told The Tablet. “Agrippino was in the midst of that.”

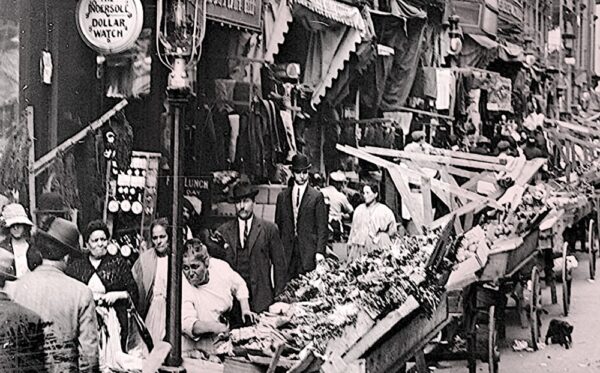

Opera dei Pupi gained new audiences in Manhattan’s Little Italy, where immigrants worked long hours for low wages to pay rent in dingy tenements. For pennies, they swapped their homesickness for the familiar performances of stories based on Giusto Lodico’s “La Storia de Paladini di Francia” (The History of the Paladins of France).

Agrippino came to New York with his wife and children in 1919, but the puppeteer delayed his New York theater launch until he had built his marionettes and wrote scripts for the performances.

His first venue was at 76 Catherine St., but by 1928, the theater was thriving on Mulberry Street.

Cavallo said the productions were illuminated by thrilling scripts based on Lodico’s “The History of the Paladins of France.” This work was first published in 1858-1860 and updated 1895-1896 by Giuseppe Leggio.

Lodico based his stories on many Renaissance poems, most notably Matteo Maria Boiardo’s “Orlando Innamorato” (1483) and Ludovico Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso” (1516). The verses relate how the paladin Orlando becomes insane after falling in love with Angelica, the princess of Cathay, but she marries someone else.

Spoiler alert: Orlando regains his sanity in time to save the realm of the Frankish King Charlemagne — ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 768 to 814.

Orlando and fellow paladins repel the invasion of Saracen armies ruled by Agramante, king of Biserta in North Africa. Legendary stories about Charlemagne and his paladins were experienced as part of a shared history in France and Italy, Cavallo said.

“After all,” she noted, “as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne had presided over an extensive Christian realm to which the various Italian states had belonged.”

Cavallo said some of these stories uniquely appealed to Catholic audiences. “When a hero died,” she explained, “an angel would descend to transport his soul to heaven.”

She also described an episode from “Orlando Innamorato” in which Orlando compassionately assists the 11th-hour conversion of a vanquished foe, the Tartar khan Agricane. The hero baptizes his former enemy, and the dying khan feels “reborn.”

“What a sweet sound I hear, mixed with a celestial melody,” Agricane says. “God, I thank you. My vision is blurred … I’m losing my energy … My strength is failing … God, welcome my soul.” And he dies.

“Agrippino Manteo stages the scene in a way that invites the audience to participate in a liturgical ritual,” Cavallo said. “Without the scripts, there would be beautifully constructed puppets, but no drama.”

Agrippino’s great-grandson, Michael J. Manteo, presided over the transfer of the puppets to the museum. He never met Papa Manteo, but he marveled at his work ethic.

“It was theater by night,” he told The Tablet. “But by day, he had to make money, so he was an electrician. This is why I think, ‘Wow, how were you able to create the stories?’

After an estimated 6,000 daily performances, Agrippino closed the theater in 1939 after the death of his youngest son, Johnny, 18, from tuberculosis. The puppeteer died in 1947.

But the stories hold up, Michael Manteo said, just like the tales of modern “Star Wars” characters or comic book superheroes. “The concept is the same, right? It’s the typical story of good and evil.”