The Supreme Court has made clear on several occasions that Congress has the plenary power to adopt immigration laws. Sadly, Congress has not passed significant immigration reform legislation in decades and will not anytime soon.

The border crisis has been prompted, in part, by many from Venezuela and other countries who are arriving at our southern border seeking asylum and relief from desperate social conditions, including, but not limited to, poverty, persecution, and a lack of freedom.

There are other legal means to address this problem, such as the creation of legal pathways of migration, a reformed asylum system, including the new sponsorship program for refugees and asylum-seekers, and better foreign policies for our southern neighbors, which address the root causes of flight. There is, however, another component of our immigration system that needs to be addressed.

This is the situation of our farmworkers — 70% of whom are foreign-born. Half are undocumented. While mechanization has reduced the need for the large numbers of farmworkers who were needed in the past, farmworkers remain integral to the present system and truly are essential workers. They keep our groceries stocked and food prices low.

The history of our farmworker programs has not been a great model for future attempts to meet our agricultural labor needs. An executive order called the Mexican Farm Labor Program established the Bracero Program in 1942, which taught us lessons regarding the use of temporary, or what might be called guest-worker, programs. The program was eventually terminated due to the abuse of workers.

In Europe, the guest-worker programs in use after World War II presented difficulties to the receiving nations. These problems have been summed up in one phrase by Swiss author Max Frisch, who said, “We asked for workers, but we got people instead.”

These essential workers are human beings who do difficult work needed by our country and who are not justly compensated nor treated with the dignity that workers deserve.

There are 10 states that use the H-2A program, the present legal means to employ temporary agricultural workers. More than 500,000 people are currently using these visas. The H-2A program allows workers to come for a particular period of time, but the process is cumbersome. Many employers fail to use it and instead rely upon undocumented labor.

To address these problems, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in the last Congress that would have modernized the program and granted several hundred thousand undocumented farmworkers a path to citizenship. However, the bill did not pass in the Senate. The new Congress should try again to adopt this important legislation.

Reform of our agricultural worker programs is badly needed. Twenty percent of these workers earned salaries below the poverty level. The average farmworker makes less than $25,000 per year, and the annual earning for a farmworker family is between $25,000-$29,999. Also, full-time employment is not available to these migrant farmworkers.

The poor treatment of farmworkers reminds us of the need for comprehensive immigration reform, as many industries in our country face a labor shortage.

Most urgently, the agricultural and other farm-related industries rely upon these workers who ensure that we can put food on our tables. Our country cannot continue to treat these farmworkers as it has in the past.

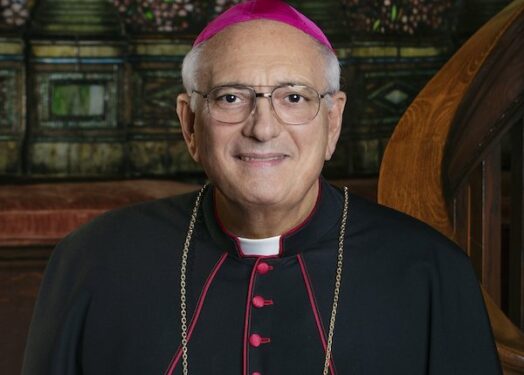

Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio, who served as the seventh bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn, is continuing his research on undocumented migration in the United States.