SUNNYSIDE — On Dec. 13, 1862, a brigade of Union infantrymen, many of them Irish Catholic immigrants who had settled in Brooklyn and Queens, attacked a fortified Confederate position along the high ground south of Fredericksburg, Virginia.

The so-called “Irish Brigade” comprised five regiments, three from New York City: the 63rd, 69th, and 88th. The troops included veterans of the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam, three months earlier, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Others were at the First Battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia in July 1861.

But none of that combat experience mattered at Fredericksburg. Waves of Irish troops assaulted the stone wall atop Marye’s Heights, only to be mowed down by Confederate marksmen and artillery. Nearly a third of the 1,600-member brigade, about 530 men, died in the deadly barrages of musket balls and cannon fire.

To commemorate these sacrifices 159 years ago, members of the modern-day 88th New York Guard marched this month to the Civil War monument at Calvary Cemetery to lay a wreath. They assembled on Saturday, Dec. 11, for the wreath-laying ceremony.

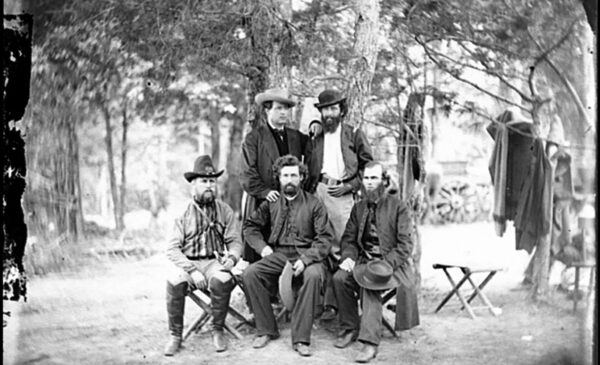

Today, the Guardsmen are not from a single cultural group. Plenty of them may have Irish heritage, but there are just as many Latinos, plus Italians and African Americans and more.

“Way back in 1862 they were fighting for their friends back home, their family, but mostly for the guys next to them — their brothers in arms,” said Master Sgt. Steve Milito, whose ancestors are Italian and Czech. “That’s the way the Guard is now.

“So we were honoring them today, not because they were Irish. We’re honoring their service.”

The spirit of service and respect for history is still embodied today in the New York Guard. It is an official “state defense force” that reports to the governor and typically serves alongside the New York National Guard in meeting the same kinds of emergency needs when called into duty.

Many states have their own volunteer defense forces, called militia in some cases, but, unlike the National Guard, forces like the New York Guard are legally precluded from taking a role beyond the state level or reporting to the President of the United States in a military capacity.

The New York Guard’s ties to the 88th Regiment of the historic Irish Brigade — and to its legacy in this part of the country — are accentuated by the Guard’s memorialization of the number 88. Members of the New York Guard standing by for duties in New York City are part of the 88th Area Command.

C’Mon, Paddy

Irish immigrants had already endured much before coming to the U.S. The current commander of the 88th, Col. Steve McNicholas, knows the stories well. His father was born in Ireland. McNicholas and Milito spoke with The Tablet to share the knowledge of the Irish Brigade which accompanies their commitment to today’s New York Guard. The story offers glimpses of the past from the city, the nation, and even a university known for “the Fighting Irish.”

“Go back in time to Ireland,” Col. McNicholas said. “Number one, they still had an overwhelming saturation of British rule, which was controlling the food supply. People were starving to death. When the potato famine happened, blight took over the potatoes; you’d pull them out of the ground and they’d be mush. So they lost the majority of their food supply.”

The Irish migration followed, said Col. McNicholas, who is a federal Immigration officer in civilian life.

“So you’d get off the boat in New York, but you have no money and no friends,” he said. “So you had to figure out a way to survive, and it seems like most of them did.”

But the Irish were resented by citizens who were born in the U.S., like the “Know Nothing” Nativists, who actively worked to promote their own culture ahead of others.

“They were working for less money,” McNicholas said of the Irish. “So they’re probably undermining employment, and there was resentment because of that.

“And nowadays we assume everybody in Ireland speaks English, but they spoke Gaelic back then, and maybe English was a second language. So people didn’t understand them.

“And remember, a lot of them were Catholic, and most people in power were Protestant, so they had that thing against them.”

But, McNicholas said, when the Union needed soldiers to stop the Confederate secession, the Irish were willing to fight.

Master Sgt. Milito explained that units received the same numeric names as the voting precincts that produced the recruits — hence the 63rd, 69th, and 88th Infantry Regiments of the Irish Brigade.

“The Irish,” he mused, “they were just getting off the boat, and what happened? The Civil War comes along.”

He imagined a conversation back in a voting district, an exchange that he said might have sounded like this: “C’mon, Paddy. We’re all going on a great adventure.”

Milito continued: “They didn’t want to be left behind, so they went along, and a lot of them lost their lives, but a lot of them also found glory and brotherhood.”

All of Us Were Sad, Very Sad

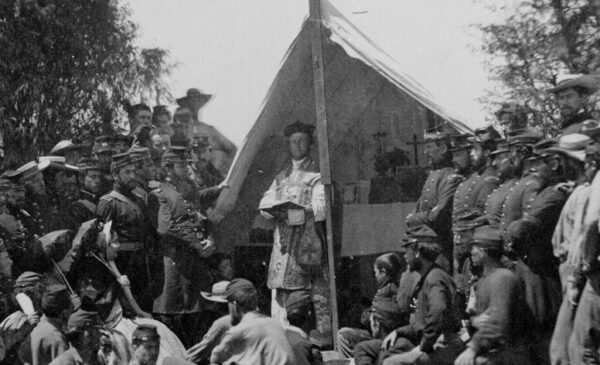

The Irish Brigade’s top-ranking chaplain was Father William Corby, a priest from Indiana, who later served as president of the University of Notre Dame. A harrowing description of Fredericksburg is succinctly told in his bestseller, “Absolution Under Fire: Three Years with the Famous Irish Brigade.

In the chapter titled “At Fredericksburg,” Father Corby described how the Irish Brigade maneuvered with the Union’s Army of the Potomac to confront Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg.

To attack, the Union forces had to cross the Rappahannock River, but the necessary pontoon bridges were late arriving at the theater of battle. Meanwhile, Lee’s forces had three weeks to dig in with lots of artillery on Marye’s Heights.

Father Corby, a member of the Congregation of Holy Cross, wrote: “One of my men said, ‘Father, they are going to lead us over in front of those guns which we have seen them placing unhindered for the past three weeks.’ I answered him, ‘Do not trouble yourself. Your generals know better than that.’ But to our great surprise, the poor soldier was right.”

He continued, “On the morning of Dec. 13, we crossed the pontoon bridges. Cheers were heard as we were going on, and some said it may be our last cry. We were ordered up front with absolutely no protection for our ranks.

“As we advanced, our men simply melted away.”

Days later, both sides went about collecting the dead and wounded from the snow-covered battlefield.

“I said Mass in the morning, but I had a very small congregation compared with former ones,” Father Corby wrote. “After Mass, the day was given to visiting the wounded, who were transferred as soon as possible to the rear where the Sanitary Commission did good, noble, charitable work, attending to the wants of the suffering, feeding them luxuriously and binding up their wounds.

“All of us were sad, very sad.”

General Absolution

Days later, a requiem Mass was held at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan, with a single casket representing the Irish Brigade’s casualties at Fredericksburg.

The unit returned to battle in the spring of 1863; by July it was deployed at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania — about 125 miles north of Fredericksburg.

On the morning of July 1, the Irish Brigade was about to join the battle already underway nearby. Vast armies had assembled once again, with the potential for immense casualties on both sides.

Knowing this, Father Corby gathered the troops and offered a “general absolution.”

Before waging war with the Confederates, the soldiers, including many Protestants, made peace with God, the chaplain wrote.

“He was dealing with non-Catholics as much as Catholics,” said Father Bryan Carney, a colonel-chaplain for the modern-day New York Guard.

Father Carney, also a hospital chaplain, celebrated Mass for members of the 88th who participated in laying the wreath at the Civil War monument on Dec. 11. After the Mass, he continued telling the story.

As the war dragged on, troops of many faiths joined together for the common cause of preserving the Union. That is why Father Corby found himself giving general absolution to Catholics and others.

“They were minutes away from a battle that most knew that they were going to die,” Father Carney said. “If you’re a Christian, you believe in the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

The general absolution, like the war itself, seemed to help dissolve animosity, at least in the Union ranks. Father Corby wrote: “The general absolution was intended for all — in quantum possum — not only for our brigade, but for all, North or South, who were susceptible to it, and who were about to appear before their judge.”

He added, “One good result of the Civil War was the removing of a great amount of prejudice. When men stand in common danger, a fraternal feeling springs up between them and generates a Christian charitable sentiment that often leads to most excellent results.”