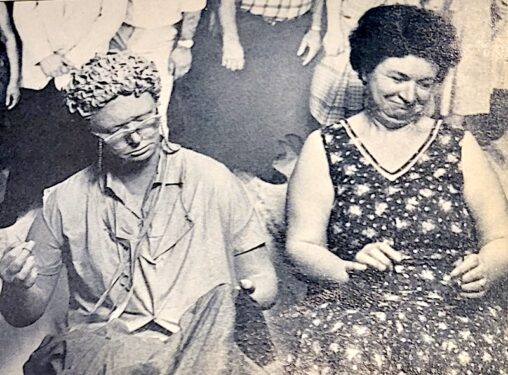

LITTLE ITALY — At 95, retired master seamstress Maria Pulsone of Flushing says she’s nothing special.

Nevertheless, there is a life-size statue of her in the new location of the Italian American Museum. It shows her seated at work, with a thimble on one finger and tiny scissors hanging from a ribbon around her neck.

Titled “Good Night, Maria,” it is one of three exhibits at the museum, located at 151 Mulberry Street, that opened to the public on Oct. 14 — Columbus Day.

Pulsone emmigrated with her family from Italy in 1955. She posed for the statue some 30 years later at the request of her bosses.

The statue of Pulsone was part of a display in the lobby of Saint Laurie Clothiers — in the Equinox Building at 897 Broadway — in the Flatiron District of Manhattan. The display was intended to show customers how their finely crafted suits were made with precision and care.

Over time, Maria’s fellow garment workers developed a tradition as they passed the statue while starting and ending their shifts.

“They would say to her, ‘Good morning, Maria! Good night, Maria!’ ” she recalled. “It was very nice over there.”

The company eventually vacated the space, and the display was dismantled. The statue’s whereabouts became a mystery.

“We had forgotten all about it and that it even still existed,” said her son, Nunzio Pulsone.

Thus, the statue temporarily faded into a footnote in the Pulsone family’s story, which began in the commune of Bojano in the Molise region of southern Italy.

A Very Particular Job

Maria was a teenager during World War II. She recalled hiding in the region’s mountains, with very little food, to avoid the carnage.

With Italy’s economy still lagging a decade after the war, Maria, her husband, Antonio, and their 6-year-old son boarded the SS Andrea Doria for the United States. They celebrated Nunzio’s 7th birthday during the voyage.

A year later, the famous ship collided with the Swedish ocean liner, MS Stockholm, and sank off the coast of Nantucket, Massachusetts, killing 46 people.

In Italy, the Pulsones were farm workers, and Antonio specialized in making various dairy products, including cheeses. He brought those skills to operations near Rochester, New York.

Maria worked at the manufacturing center for Bond Clothiers in Rochester. She knew how to sew embroidery but not the precision stitching needed to join armhole seams on men’s suit coats. Still, patient coworkers taught her the skills.

“That’s a very particular job,” Maria said. “You gotta make it even and nice. Otherwise, the garment is ‘poof.’ ”

Paid Per Suit

The Pulsone family later moved to Queens. Antonio worked in construction, and Maria became a master seamstress in New York City’s garment industry.

Jennifer Pulsone, Nunzio’s daughter, said her grandmother was paid “per suit” and often worked on garments during her mass-transit commute back to Queens.

Maria and Antonio purchased the home where she still resides. The family belonged to St. Ann Parish in Flushing, but these days, Maria watches Mass on the television.

Maria retired to take care of Antonio, who suffered multiple strokes. He passed away in 1999. She now focuses on her family.

Nunzio, who is her only child, has two children with his wife, also named Maria. Jennifer lives with her family in Manhattan, and Denise lives with her family in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Photos of grandchildren and great-grandchildren cover her walls, mingled with portraits of saints, Jesus, and Mary. Maria motioned to her sofa and an end table that holds her rosary, a devotion booklet, and prayer cards.

“I pray for everybody,” she said.

‘Woman, Sewing, Statue’

The statue remained a distant memory until September 2023, when Jennifer’s husband, Brian Heppner, inquired about it. With its whereabouts unknown, he resolved to find it.

Jennifer said he “Googled it” with the words “woman,” “sewing,” and “statue.”

A few clicks later, photos of the statue splashed onto his computer screen from the website of a national antiques dealer, Olde Good Things. The statue was titled “Life Like Statue of a Sewing Woman in a Chair.”

The listed location was the company’s national warehouse in Scranton, Pennsylvania. How it got there still remains a mystery.

Jennifer called the company and arranged to buy it. The company agreed to hold it until the family figured out where to put it because it was too big for anyone’s home.

She emailed museums to see if they might take it as a donation. Among them was Dr. Joseph Scelsa, founder and president of the Italian American Museum. He replied swiftly.

“I said, ‘I gotta have it for the museum,’ ” he recalled. “That one statue says it all.”

Backbone of the Family

Scelsa explained that the image of Maria at work exemplifies the Italian culture’s love for family and the zeal to provide for it through hard work.

“Unfortunately, the story of these women doesn’t always get told,” Scelsa said. “Oftentimes, they are the backbone of a family. They not only cooked and cleaned, but they also worked outside the home. And they did it without complaining, just to help support the family.

“In that sense, Maria Pulsone represents all of these women.”

Nunzio said his mother’s most important legacy is the faith she shared with her family.

“Her influence,” he said, “has made us better Catholics, with going to Mass, prayer, and receiving the sacraments.”

‘Proud for My Family’

Jennifer said she is proud that the statue represents the Italian contributions to the U.S. Still, her grandparents uniquely blessed their family.

“They had no money when they came here and they created a better life for my father, which, in turn, created a better life for me and my sister,” she said. “I have such an appreciation for their struggles, and I’m so grateful to them.”

Maria said she never believed the statue was a big deal, but she knows it now has a special role.

“I’m proud for my family,” she said. “Sometimes, they will want to come to the museum, and they can say, ‘That’s my grandma. That’s my great grandma.’ ”

Another wonderful story by senior writer Bill Miller. God bless Maria and her statue which now continues her legacy. It makes me want to visit the museum and see it in person. Thank you for sharing this!