ASTORIA — In Taguig City, Philippines, there is a cemetery with the graves of 16,636 American service members killed in the Pacific Theater of World War II.

Known as “The Manila American Cemetery,” it also contains 36,300 names on the “Walls of the Missing,” including 2nd Lt. Peter Chappetto, 32, of Astoria, Queens.

He died Sept. 26, 1944, from wounds sustained a few days before in the Battle of Angaur, part of the Mariana and Palau Islands Campaign in the South Pacific.

However, history professor Erik Carlson told an audience on Sept. 26 at Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Astoria — the Chappetto family’s parish — that this infantry officer is not “Missing in Action.” On a map of the South Pacific, Carlson identified the equator — 0 degrees latitude, and then, slightly to the right, the longitude of 145 degrees east.

“This is the approximate place in the Pacific Ocean where Peter Chappetto’s body was committed to the deep,” Carlson said. “It’s a long way from Astoria, New York.”

With no physical grave either in the Philippines or Astoria, Chappetto’s family took steps to ensure his name endures. Chappetto Square was formed in 1949 from a 1.25- acre playground — formerly known as the “Cheesebox” because of its shape — on Hoyt Avenue between 21st and 23rd Streets.

Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus Raymond Chappetto, the lieutenant’s nephew, hosted a park rededication on Sept. 26, the 80th anniversary of the soldier’s death, before going to Our Lady of Mount Carmel for Carlson’s presentation.

Bishop Chappetto described to The Tablet how his father, Lou, regularly brought his wife and their five sons to the square beneath the Triboro Bridge to honor Lt. Chappetto.

Bishop Chappetto, the middle son, never met his uncle; he was born a year after the soldier’s death. “My father would say, ‘We’re going to Uncle Pete’s Park,’ ” Bishop Chappetto said. “It was very close; we could walk. And we’d stand by the flagpole, and we would remember him in prayer. It was like our place of grieving, like our cemetery.”

Wildcats

Peter Chappetto was born in 1912, the youngest of three children — two sons and a daughter — in the family of Charles and Dora Chappetto.

He excelled in baseball and basketball and captained both teams at William Cullen Bryant High School in Long Island City. After graduation, the humble and soft-spoken “Pistol Pete” continued to impress as a standout semi-pro in both sports.

Meanwhile, he scaled the career ladder at Breyers Ice Cream Company. But, as war loomed globally in the early 1940s, Chappetto enlisted. He had been in the U.S. Army for nearly a year when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

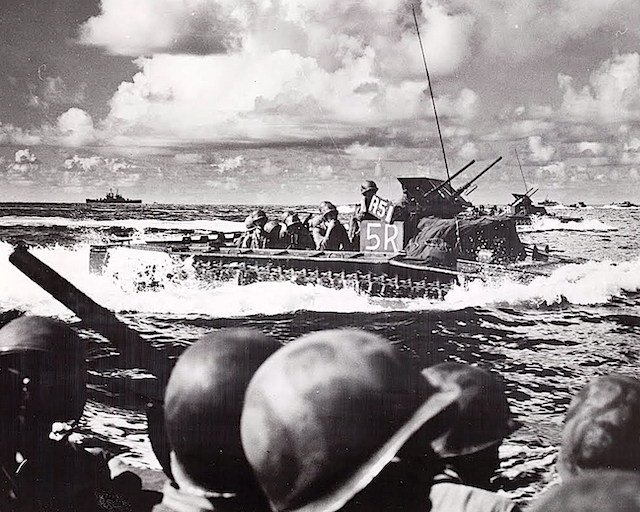

By the summer of 1944, Chappetto was a second lieutenant in Company D of the 321st Infantry Regiment of the 81st Infantry Division — the “Wildcat Division.” On Sept. 17, it stormed the “Blue Beach” on the Japanese-held Angaur Island.

Counterattack

Carlson is a military historian at Florida Gulf Coast University in Fort Myers.

He described how Lt. Chappetto’s unit made a flanking maneuver in a counterattack on Japanese troops charging from fortified pillboxes and caves to repel the Americans. The company commander was killed, so Chappetto took control. He ordered his troops to pull back to a safer position about 100 yards away, but he stayed put to cover them.

“And this is where he is hit by light machine gun fire and also mortar fragments, and he will be mortally wounded,” Carlson said.

Committed to the Deep

Chappetto was taken aboard an attack transport, the USS Sumpter, for evacuation to a field hospital on one of the Admiralty Islands north of New Guinea, but he died en route on Sept. 26, Carlson said.

There were no mortuary facilities aboard the Sumpter. Consequently, Chappetto became one of seven soldiers from the 81st Division to be buried at sea — a very solemn ceremony, Carlson added.

The Army posthumously conferred him with the Purple Heart, Bronze Star, and Silver Star. Beyond the medals, 30 of Lt. Chappetto’s unit members signed a letter to his parents, dated Dec. 22, 1944, to express their appreciation for his valor.

They wrote, “The reason he is not with us today is because he thought more of the safety of his men than he did of his own.”

Our Best Example

Carlson first contacted Bishop Chappetto a few years ago while researching an upcoming book about the Wildcat Division. His scholarly interests subsequently grew beyond battle records to include how surviving service members, families, and communities honor those who died in war.

For example, Carlson described a “first phase” in which troops from the 81st built a large cemetery with a stone chapel on Angaur for their comrades. All the graves were moved to Manila American Cemetery, but the people of Angaur still maintain the grounds.

“I’m also interested in the ‘second phase’ in the post-war period, where families, wives, fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, families, commemorate the legacy and the sacrifice of a loved one,” Carlson said.

“Our best example,” he added, “is what Bishop Chappetto’s family did in 1949 when they dedicated the [Square].”

Bishop Chappetto is the guardian of his uncle’s medals and other keepsakes from the war, but he hopes to one day turn that task over to his own nieces and nephews — a task started by his father.

“That was his way of, I guess, passing on the legacy to us,” Bishop Chappetto said. “It was his way of teaching us about his brother and helping us to understand the price that he paid for our country.”

Thanks to senior writer Bill Miller for an excellent article. I have known Bishop Chappetto for years and never knew he had a hero Uncle who has a park named for him in Astoria. I’m also fascinated that he has his Uncle’s medals. As a career Air Force officer with two tours in Vietnam, I hope someday to see these medals. This story has more photos than was available in the Tablet article. Coincidentally, I was able to visit the Manila American Cemetery in 1970 and the Punchbowl in Honolulu in 1971. Since Lt. Chappetto was buried at sea I don’t understand why his name was posted on the Missing In Action wall. Technically he wasn’t missing but honorably

buried at sea.