TIMES SQUARE — Thousands of tourists, cartoon-costumed hawkers, theater-goers, and homeless souls pass each day beneath the glitzy digital billboards of the so-called “Crossroads of the World” — Time Square.

Standing watch over this seemingly never-ending procession is the bronze statue of a stoic, yet steadfast soldier clad in the uniform of the U.S. Army World War I “doughboy,” gripping a Bible with both hands. But in life, this man’s usual garb was the collar and cassock of a Catholic priest.

Father Francis Duffy’s priestly career began on the faculty of St. Joseph’s Seminary at Dunwoodie, Yonkers. Later, he served as pastor in the Bronx and Manhattan.

The Canadian-born priest became a prominent New York City leader who was enlisted by New York Gov. Al Smith to be the “ghost writer” of a special letter. That missive argued that Smith’s Catholic faith should not keep him from campaigning for the presidency in 1928.

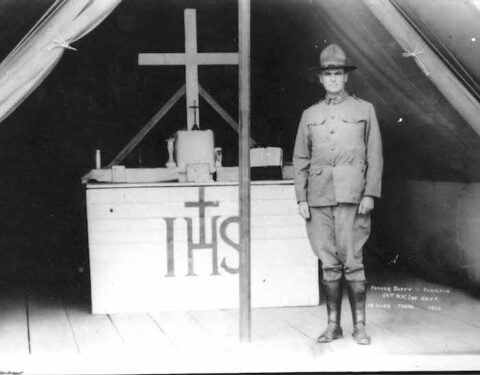

But the priest’s prominence originated as 1st Lt. (and, later, Lt. Col.) Francis Duffy, chaplain of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment — the celebrated “Fighting 69th.”

If his statue’s steely gaze seems out of place amid the frivolity of Times Square, consider that this chaplain saw immense carnage as the 69th pushed through France during the final months of the “Great War.”

In his war memoir, Father Duffy wrote, “We ran up and I found one of ours with both legs blown completely off. … I gave him absolution. He had no idea his legs were gone until a soldier lifted him on a stretcher. … He started to look, but I placed my hand on his chest to keep him from seeing.”

Early Controversy

Father Duffy, born 1871 in Cobourg, Ontario, received ordination at age 25 in the Archdiocese of New York. He earned a doctorate in 1905 from The Catholic University of America.

Although he gained prominence during the war, and later years in New York City, Father Duffy had an early brush with controversy.

At Dunwoodie he became a professor of philosophy and editor of the New York Review, a Catholic newspaper at the seminary. The staff drew heat from the Vatican when it published articles that were interpreted to represent the “heresy of modernism.”

At Dunwoodie he became a professor of philosophy and editor of the New York Review, a Catholic newspaper at the seminary. The staff drew heat from the Vatican when it published articles that were interpreted to represent the “heresy of modernism.”

Father Michael Bruno, the Cardinal Spellman Chair of Church History at St. Joseph’s Seminary, described modernism as a “theological crisis of the early 20th century.”

It emerged “when authors and movements sought the adaptation of doctrine based on scientific advancements and other contemporary trends,” Father Bruno said. “This controversy was deeply felt in Scripture studies,” he added.

It also festered in discussions over Church philosophy and its approach to political and social conditions, Father Bruno said. Pope Pius X in 1907 condemned modernism, in his encyclical “Pascendi Dominici Gregis,” he said.

“It is true that at the time Rome raised concerns about various seminary faculties, including Dunwoodie and its rector, Father James Driscoll,” Father Bruno said. “The New York Review would publish its last issue in Spring 1908.”

Meanwhile, Father Duffy remained on the faculty until 1912, when he was sent to create Our Savior Parish in the Bronx, Father Bruno said.

My Protestant Fellows

Father Duffy’s war memoir was to be co-authored by the popular poet and journalist Joyce Kilmer, who enlisted in the 69th when the U.S. entered the war in April 1917.

Sgt. Kilmer, who penned the popular poem, “Trees,” managed to complete the memoir’s historical appendix while in France. A sniper’s bullet, however, killed him before the manuscript’s completion.

The chaplain subsequently completed the work on his own. Its title: “Father Duffy’s Story — A Tale of Humor and Heroism, of Life and Death, with the Fighting Sixty-Ninth.”

In it, he describes how young men rushed to join the regiment. The 69th had a colorful history of valor and sacrifice going back to the Civil War when New York City’s maligned Irish immigrants vowed to prove their patriotism.

“The Catholic clergy were asked to send good men from the parish athletic clubs,” Father Duffy wrote of the recruiting in 1917. “Our 2,000 men were a picked lot. A number of these latter Irish bore distinctly German, French, Italian, or Polish names. They were Irish by adoption, Irish by association, or Irish by conviction.”

Still, he noted, the 69th “never attempted to set up any religious test.” Father Duffy wrote, “It was an institution offered to the nation by a people grateful for liberty, and it always welcomed and made part of it any American citizen who desired to serve in it.”

In the tradition of the Army’s chaplain corps, Father Duffy cared for all soldiers, regardless of religion. When the regiment reached the town of Baccarat, for example, he set out to “see if there were services in town that I could announce to my Protestant fellows.”

Grit in Grim Circumstances

Father Duffy’s service is well documented at the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps Museum at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. According to its archives, he routinely roamed the trenches and forward positions, hearing confessions, serving the Eucharist, and giving last rites. He became an eager stretcher-bearer, bringing the wounded to aid stations.

“Duffy was wounded at the front lines and received the Distinguished Service Cross,” said Marcia McManus, the museum’s director. “France also awarded him the Croix de Guerre medal.”

In the memoir, the chaplain offered graphic battlefield descriptions, like men suffering dismemberment or death. Sometimes the soldiers expressed grit in their grim circumstances.

“Harry McCoun was struck by a shell which carried away his left hand,” Father Duffy wrote. “He held up the stump and shouted, ‘Well, boys, there goes my left wing.’

“McCoun died the next morning.”

Enemy and Friend

Father Duffy also showed care and respect for the enemy.

He noted the German military’s decency in how it treated the battlefield grave of Lt. Quentin Roosevelt, son of former President Theodore Roosevelt. The young pilot died in aerial combat.

“We found the roughly made cross formed from pieces of his broken plane that the Germans had set to mark the place where they buried him,” Father Duffy wrote. “We erected our own little monument without molesting the one that had been left by the Germans. It is fitting that enemy and friend alike should pay tribute to heroism.”

According to the museum, Father Duffy also celebrated Mass for German prisoners, jammed into a local church with American troops. He led the former enemies in singing the hymn, “Holy God We Praise Thy Name.”

“The Germans,” he wrote, “swelled our chorus in their own language — ‘Grosser Gott Wir Loben Dich.’”

Shrewd Move by Smith

After the war, Father Duffy returned to Manhattan to pastor Holy Cross Parish in Hell’s Kitchen, a short distance from Times Square.

Meanwhile, New York’s popular governor, Alfred E. Smith, and his Catholic faith drew criticism upon winning the Democratic Party’s nomination to run for president in 1928.

“It was a historic moment for a Catholic to get the nomination,” said Brian Browne, political science professor at St. John’s University. “But Al Smith was also a victim of the time. In 1928, it was tough for a Catholic, particularly an Irish Catholic, and a child of immigrants, to be a national candidate.”

Immigrants, Browne explained, still contended with suspicions held by native-born citizens. The Catholic faith, he added, drew even more suspicions.

“They were associated,” he said, “with this hierarchical institution — the Catholic Church. So people were questioning their allegiance to Rome and the pope, versus their allegiance to the country.”

But Smith turned to Father Duffy for help. Together they created a letter titled “Catholic and Patriot” that appeared in The Atlantic.

The letter concluded:

“I believe in the worship of God according to the faith and practice of the Roman Catholic Church. I recognize no power in the institutions of my Church to interfere with the operations of the Constitution of the United States or the enforcement of the law of the land.

“I believe in absolute freedom of conscience for all men and in equality of all churches, all sects, and all beliefs before the law as a matter of right and not as a matter of favor. I believe in the absolute separation of Church and State and in the strict enforcement of the provisions of the Constitution that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

“In this spirit I join with fellow Americans of all creeds in a fervent prayer that never again in this land will any public servant be challenged because of the faith in which he has tried to walk humbly with his God.”

Browne noted that Herbert Hoover, the GOP candidate, “shellacked” Smith in a landslide. Still, the Smith candidacy punched a hole through the glass ceiling of anti-Catholic sentiment in political arenas. In so doing, it also paved the way for successful races run by Catholic candidates, such as John F. Kennedy, Browne said.

“It’s an interesting case study on how religion could rise to such an issue, and how Smith leaned on another local New Yorker to help answer those charges,” Browne said. “Catholics and Protestants fought side by side during World War I, and no one knew that better than Duffy. So I think it was a shrewd move by Smith to get him involved.”

Legacy

Father Duffy died in 1932 at age 61.

In 1940, a movie about Father Duffy was released, titled “The Fighting 69th.” Pat O’Brien starred as Father Duffy, and James Cagney was one of the doughboys.

Father Bruno, in describing the chaplain’s legacy, referred to the writings of a chronicler for the seminary, the late Msgr. Thomas Shelley.

He quoted, “Despite the physical and psychological strain of his responsibilities, Duffy said that he never regretted his decision to volunteer as a chaplain. A priest’s home is in the parish he is assigned to, and the old 69th is a mighty comforting parish.”

Thank you again for an informative article and photos. His statue stands out in Times Square not far from the Broadway legend George M. Cohan. One stands for Broadway and the other for God! Both men are buried in the Bronx. Cohan is in Woodlawn Cemetery and Father Duffy is in St. Raymond’s Cemetery. There is a plaque in front of Holy Cross Church honoring Father Duffy as Pastor from 1921 to 1932. His service/heroism as a WWI Chaplain resembles my hero Servant of God/Medal of Honor recipient Navy Chaplain Father Vincent R. Capodanno M.M. who was killed in Vietnam and is buried on Staten Island at St. Peter’s Cemetery. God bless both of them and all our Chaplains serving our miliitary and thier families around the world!

While a seventh grader at Sacred Heart School in East Glendale, the one book I read over and over was “Fighting Father Duffy.” It was a wonderful story portraying Fr. Duffy the way he’s described in your piece. I was excited to find out many, many years later that my dear friend’s uncle was part of the 69th regiment!