FLATLANDS — Father Dwayne Davis stood in the “Door of No Return” on Gorée Island, Senegal, and imagined the fate of Africans swept into the Atlantic slave trade.

Father Davis toured this island’s “Maison des Esclaves” (House of Slaves) during the summer with 17 teens and young adults from parishes in the Diocese of Brooklyn.

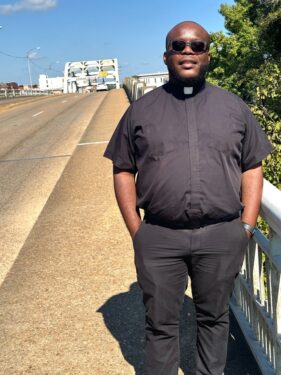

In October, he walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama — an iconic location in the Civil Rights movement.

Father Davis said the two trips formed a “full circle” experience and gave him deeper perspectives of the horrors endured by black people from the 1500s to the 1960s.

“So much history comes back to you,” he said of the back-to-back trips. “You begin to feel the emotions.”

Father Davis is pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas Parish in the Flatlands area of Brooklyn, where many young parishioners participate in the Youth Leadership Ambassador Program of the diocese’s Vicariate of Black Catholic Concerns.

Father Davis accompanied ambassadors from June 27 to July 8 on a summer missionary trip to three African countries — Ghana, Senegal, and Morocco. They visited and worked at churches, schools, orphanages, and soup kitchens. They also toured the House of Slaves on Gorée Island and Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle.

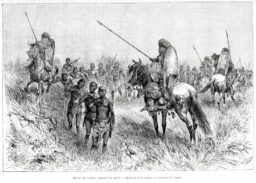

Kidnapped people from the African interior were shackled and marched to slave forts or “castles” on the continent’s west coast. There, they awaited ship transport to lives of slave labor in the Western Hemisphere while living in cramped, unsanitary dungeons.

An estimated 15 million men, women, and children were forced into the Atlantic slave trade from the 1500s to the late 1800s. Many died of disease or violence in the dungeons or aboard the slave ships. Survivors and succeeding generations endured lives of harsh forced labor, torture, and separation.

Father Davis said that the “door of no return” at the House of Slaves is a unique symbol of this longtime injustice.

“The slaves would go through this door to be placed on a ship,” he explained. “From there, they were shipped out to one of the colonies in North America, Central America, or the Caribbean, and they didn’t return.”

Seeing the dungeons was powerful and depressing for the ambassadors, according to Father Davis, who noted that the group was silent, somber, and reflective throughout.

At Cape Coast Castle, the group learned that the dungeon floors were actually a veneer of dried, compacted human waste. Adriana Dorner, a parishioner at St. Thomas Aquinas, said a slight but noticeable stench still lingers in the cells.

“You would think it’s just stone or something,” Dorner said. “But it’s [human waste} … it’s everything, caked up, and it became part of it.”

Dorner attends St. Francis College in Brooklyn and plans to become a social worker. She said it saddened her to imagine her ancestors in such conditions.

“It was just rows and rows and rows of people,” Dorner said. “There was not even enough space to turn to your side. You could see the nail marks from people scratching, trying to claw their way out.”

Christian Lafontant, also from St. Thomas Aquinas, called the experience humbling. He said it made him grateful for his tiny college dorm room at Babson College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, where he is studying business.

“At Gorée Island,” Lafontant said, “you could be packed with like 50, 100, or 200 people in a small room … malnourished, thirsty, and barely any clothes.

“My room is small, but it’s my room, and it’s my space.”

In Alabama, Father Davis joined other priests on a Catholic Extension Society immersion trip. He said they observed the extension’s missionary work in impoverished areas like Africatown near Mobile — a community founded by 30 Nigerian people smuggled to the United States in 1860. This was an illegal operation because the Atlantic slave trade was outlawed in 1807.

The extension group took time to visit Edmund Pettus Bridge, which was on the 53-mile route of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches to protest racial injustices and promote the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In March 1965, groups of peaceful activists, including Catholic clergy and religious, made two attempts to cross the bridge but were turned back, sometimes repelled violently by police.

A third try on March 21 included Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the front line of activists. This time they passed with the protection of a federal court order proclaiming their First Amendment rights to protest.

Father Davis said he gained a new appreciation for the Church after observing the work of the Catholic Extension Society and learning about how Catholics participated in the Civil Rights movement. He noted he gained a stronger understanding of how the Church evolved during those four centuries to become a source of the Gospel’s gifts to all people, as well.

Father Davis acknowledged there were Catholics who participated in slavery, but he also credited modern-day Jesuits for seeking to repair its ownership and sale of slaves from the plantations they owned in Maryland.

“We need to be a people of reconciliation,” Father Davis said, “and to help people, to not forget their history, but to move forward in hope.”