Do you commemorate or observe an anniversary? It all depends on how you see it, either as a positive or a negative event. This is the very case that we have today with the anniversary of the 1924 Immigration Act, which severely curtailed immigration from Southern and Eastern European countries as well as Asian nations. There are those who believe that this so-called pause in immigration had beneficial effects on the already-settled immigrants themselves, since they were able to make greater progress with less competition. Some allege that it enabled Southern blacks to migrate to the North, which improved their economic conditions.

Careful analysis of the law must also include the intention of the lawmakers in enacting an anti-immigrant law based on national origin and not simply the curtailment of entrants. Those excluded were deemed unacceptable to the future of American society. Eugenics and other anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic prejudices such as the influence of the Ku Klux Klan contributed to the passage of this very discriminatory law. Some today even try to hail it for its unproven positive effects.

Some concrete examples of the law’s effect will prove the case. One year after the passage of the law, overall immigration had fallen from approximately 700,000 to 300,000, a trend that remained in effect for many years to come. Specific countries also had dramatic losses: Poland went from 31,000 to 6,500; Italy from 42,000 to 5,000; and Russia from 24,000 to 3,000, which reduced Jewish migration significantly.

There were other restrictions on Asian immigration which made it nearly impossible for Asians to migrate to the U.S. Other new regulatory restrictions were put into place, especially enforcement of public charge provisions, meaning that prospective immigrants could not access any benefits in the United States. The act also removed the statute of limitations allowing for deportation at any time if an alien stayed in violation of the law, where previously there was a five-year statute. Immigration from the Western hemisphere (North and South America) was effectively reduced to a trickle.

Immigration history seems to have repeated itself. Today’s so-called replacement theory, meaning that the admission of new non-white immigrants is a plot to change the character of American society, is a case in point. Present-day attitudes favoring restrictions are, unfortunately, generated from the same type of prejudices that enabled the 1924 law to go into effect. The unfortunate heritage of that law still reverberates in our society today.

Completing this short immigration history survey might be appropriate at this time. In 1952, an attempt was made to correct the deleterious effect of the 1924 act. Although the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 was vetoed by President Truman, it was overridden by both the House and Senate. It went into effect and improved the 1924 act very little. Not until 1965, when the present general law was changed, did the national origins quota system become part of history’s trash bin. The 1965 law theoretically allowed for every country in the world to have an annual quota of 20,000, based on family relationships and labor needs. Although this law significantly changed the discriminatory effects of the 1924 law, after more than 50 years it has proven inadequate to deal with the present-day reality of labor needs, family re-reunification and protections for vulnerable aliens.

The anniversary of the 1924 Immigration Act should be commemorated as a blot on our immigration history, not a milestone to be observed.

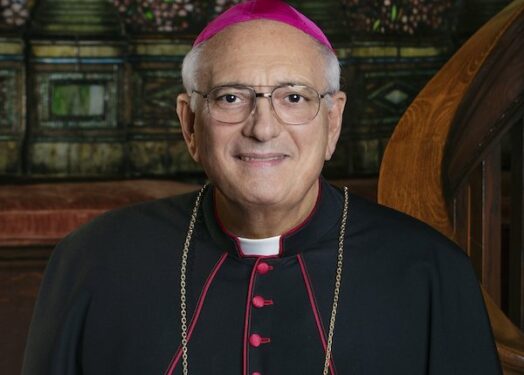

Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio, who served as the seventh bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn, is continuing his research on undocumented migration in the United States.