PROSPECT HEIGHTS — Bishop Emeritus Nicholas DiMarzio recalled how, in 2006, as a winter storm heaped drifts of wet snow on Brooklyn, a national teachers union leader came to visit.

Randi Weingarten, then the president of the United Federation of Teachers, urged him to drop his support of a bill in the Legislature to allow educational tax credits for donations to parochial school scholarships.

Still, the teachers’ unions have long held that any government aid to parochial schools diverts enrollments from public schools where their members have jobs.

“It was one of those days when they tell you to stay home, don’t drive,” said Bishop DiMarzio, who retired in 2021. “But she came in the middle of the snowstorm to try to convince me.

“We were so close [to getting the bill passed] that they were afraid that it was going to work.”

The Legislature, however, did not pass the bill. Nor did it pass a similar measure in 2018. In both attempts, the state government sided with the unions, according to James Cultrara, director for education at the New York State Catholic Conference. He noted that the bills also requested tax credits for donations to public school scholarships.

If these bills were considered on their merits, they “would have been enacted 40 years ago,” Cultrara said.

“But it’s not on the merits,” he added. “It’s about public school union jobs versus families. It’s a very fragile marketplace. And the public school teachers’ unions are trying to maintain control and dominance of the marketplace.”

It wasn’t always so in New York.

From the nation’s founding in the late 1700s until the mid-to-late 1800s, local governments funded parochial and nonsectarian schools the same, said James Wolfinger, dean of the School of Education at St. John’s University.

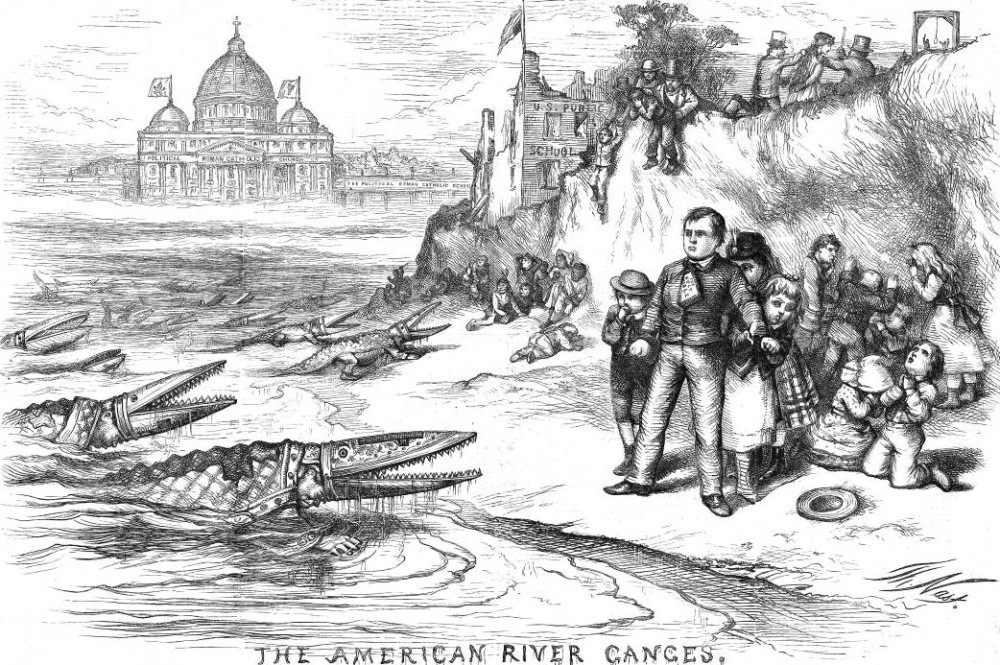

But that changed as “nativism” clashed with immigration soon after the Civil War, especially in New York City — a hotbed for entrenched anti-newcomer attitudes.

Wolfinger explained how immigrants were accused of taking jobs, housing, and political influence from native-born folks.

“So many of the waves of immigrants were from Southern and Eastern Europe,” he said. “And they were Catholic, coming to a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant nation.”

Around the same time, Wolfinger said state governments became responsible for licensing certain professions, including doctors, lawyers, and teachers. The states subsequently gained more power in education. So, when Catholics sought to teach, for example, the pope’s infallibility, the pushback was immense.

“The larger American society said, ‘Whoa, what are we doing here? We’re not funding that anymore.’’” Wolfinger said.

Government funding dwindled.

Still, parochial schools subsisted on the religious communities (parishes) formed by the growing immigrant populations. Such was the world when Bishop DiMarzio was born 80 years ago in Newark.

He said religious sisters predominately ran the schools and taught the students. Overhead was low because the sisters, fulfilling their vocations as educators, lived on stipends.

But as they retired, religious communities grew smaller. With fewer sisters available, the schools employed more lay teachers but had to compete with public school salaries.

Payrolls grew, and the once-affordable Catholic education became less possible for many families, said Bishop DiMarzio, who was installed in 2003. Meanwhile, he said, Catholic school enrollments also declined; less students spelled fewer tuition dollars.

Schools closed.

“When I came, there were 125 schools,” Bishop DiMarzio said. “Now you’re down to 70. It wasn’t like we wanted to close them, but we had no choice.”

Hence the appeals for government aid.

However, as of this writing, no specific “school choice” bills are planned for future legislative sessions in New York, Cultrara confirmed.

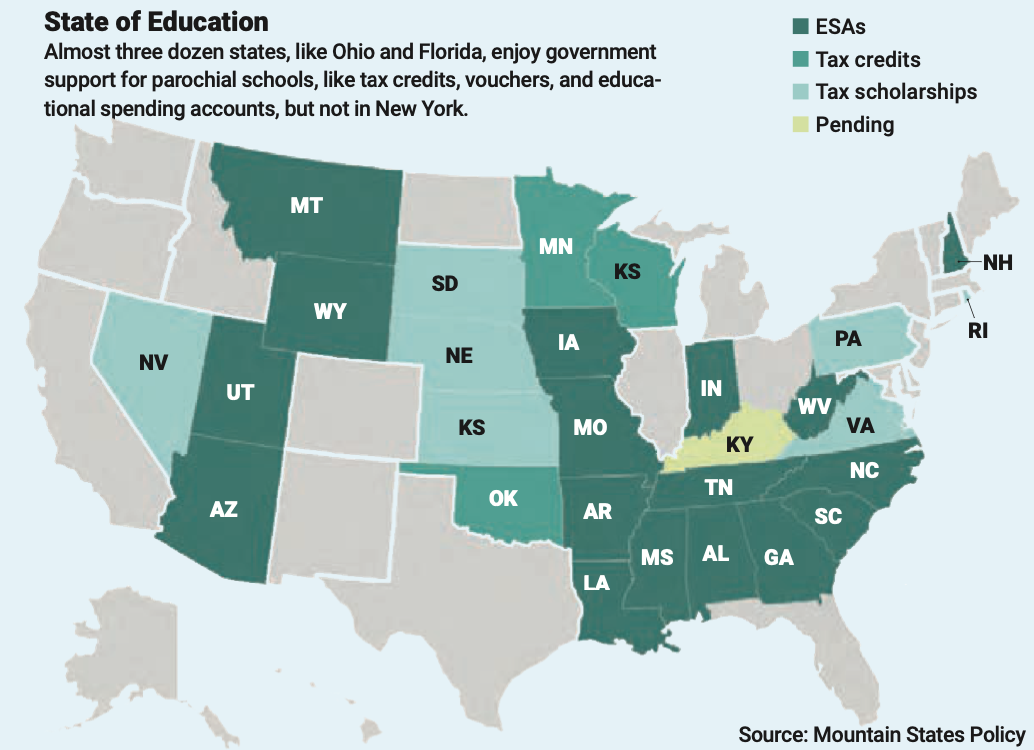

Meanwhile, 35 other states enjoy government support for parochial schools, like tax credits, vouchers, and educational spending accounts.

Marty Golden, a former Republican state senator from Bay Ridge, introduced the tax credit bills in the Senate. Bishop DiMarzio and Cultrara praised him as a champion for Catholic school education.

Golden recently told The Tablet that legislation was common sense. He asserted that robust parochial school enrollments help ease the burdens of overcrowded public school classrooms.

Also, Golden said, the quality of education improves across the board when parents have more choices to educate their children. But he said he was unaware of anyone in the government ready to pick up where he stopped in 2018 when he lost his re-election bid.

But whoever steps up will have a tough fight, Golden said.

He explained that, unlike when he was a senator, the Democrats now control the governor’s office, plus both houses of the Legislature. He argued for the “checks and balances” that come when both Democrats and Republicans have power in state government.

“The governor should set up a committee with the Senate and the Assembly and move forward on a bill that would give the parochial schools the money they need to educate children,” Golden said.

It’s a “dollars-and-cents issue” for some, said Golden, who warned that pushback will persist from legislators who oppose the “orthodoxy’’ of religious education.

However, according to Bishop DiMarzio, these lessons are essential for ensuring the faith has a future in the U.S. He said the complexities of the faith get much more attention in a daily Catholic school setting than in a weekly religious education class.

“It’s good for everybody,” he said, “but it’s certainly very important for us.”