WINDSOR TERRACE — There have been Catholics in China since the Tang Dynasty in the 8th Century. But China has had a complicated relationship with the church — especially over the past 71 years when Communists have controlled the country. Even today, many Catholics there worship in secret.

Bishop Francis Xavier Ford (1892-1952) had already been serving as a Maryknoll missionary in China for 31 years by the time the Communists took control of the country in 1949 and founded the People’s Republic of China.

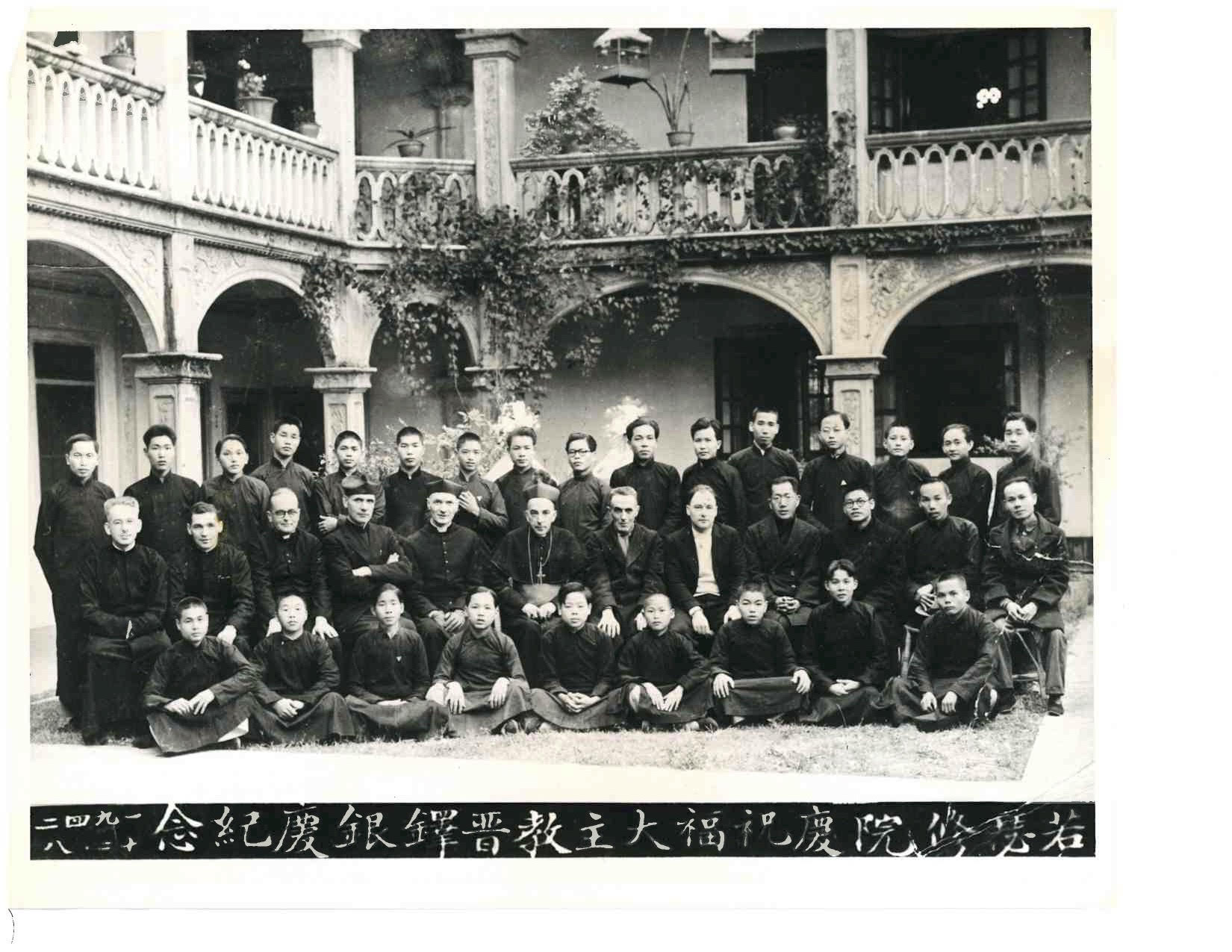

In his three decades in China, Bishop Ford, who spoke the language, demonstrated great respect for Asian traditions and built a trusting relationship with Chinese Catholics. “He loved China. He loved the Chinese people. He was a model of evangelization,” said Auxiliary Bishop Raymond Chappetto, Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio’s liaison to the Bishop Ford Committee and the official spokesperson of the committee for Bishop Ford.

None of it mattered to the Communists. The government considered religious leaders like Bishop Ford spies and condemned them as symbols of Western imperialism.

[Related: Bishop Ford Guild Promotes Sainthood for Brooklyn-Born Missionary]

In 1950, Bishop Ford was arrested on espionage charges and thrown into a prison camp, where he was tortured. He died in 1952. “He is like the pinnacle martyr,” said Father Kevin Hanlon M.M., a Maryknoll priest who serves on the theological commission for Bishop Ford’s canonization effort.

Bishop Ford’s fate was also the fate of other members of the clergy at that time. If they weren’t imprisoned, they were thrown out of the country. Bishop Edward Walsh, a Maryknoll missionary who arrived in China in 1918 with Bishop Ford, was sent to a prison camp in 1958. He survived his ordeal and was released in 1970.

As a result of the government crackdown, many Catholics went underground — meeting in secret to spread the Gospel.

In 1957, the government decided to permit Catholics to practice their religion openly — albeit under strict Communist control.

The government established the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association to oversee the church. Members must declare that their first allegiance is to China, not the pope. Bishops are not permitted to speak out publicly against abortion or contraception.

The Vatican does not recognize the CPCA, and since 1958, bishops who belonged to it were excommunicated because the government and not the Vatican appointed them.

Since the 1980s, the Vatican has recognized some bishops and priests’ legitimacy in the CPCA, but on an individual case-by-case basis.

With the founding of the CPCA, the Catholic Church in China became splintered. Catholics who did not wish to belong to the government-sanctioned church remained underground, their loyalties to the pope intact.

Pope Francis is seeking reconciliation between the CPCA and the underground church.

In 2018, the pontiff signed an agreement with China to set up a framework for appointing bishops. At around that same time, the pope formally recognized seven bishops who had been appointed by the government.

“Regrettably, as we know, the recent history of the Catholic Church in China has been marked by deep and painful tensions, hurts and divisions, centered especially on the figure of the bishop as the guardian of the authenticity of the faith and as guarantor of ecclesial communion,” Pope Francis wrote in a message.

Underground Catholics have criticized his actions, questioning why they had endured suffering at the government’s hands and had adhered to their faith only to see the leader of the world’s Catholics cooperating with the Communists.

Today, life for foreign Catholic clergy in China is different from Bishop Ford’s day.

The government doesn’t throw foreign priests into prison camps. “They wouldn’t dare,” said Father Larry Lewis M.M., a Maryknoll missionary who lived there for several years.

But priests feel like they are being watched all the time by the government. “I was careful with emails,” Father Lewis said.

“The last time I was there was in 2018,” Father Lewis said. He traveled to China for a reunion with former students.

Father Lewis was impressed by the depth of devotion to the Catholic Church in China. “They have a tremendous love of the faith,” he said.

Father Lewis lived and taught in China during the anti-government demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989. He did not take part in the protests. But he did allow protesters to come to his apartment for coffee.

Father Lewis served as the Maryknoll China Educators and Formaters Project coordinator, a program established in 1991 where seminarians from China come to New York to study.

Through the China Project, Father Lewis had the opportunity to attend ordinations in China. He has fond memories of one ordination he attended in Wuhan.

“I was the only foreigner there,” he said. He met an elderly man held in the same prison camp as Bishop Ford and remembered the late bishop’s humanity during captivity.

“When he passed me, he always smiled at me,” the man told Father Lewis.