By Inés San Martín

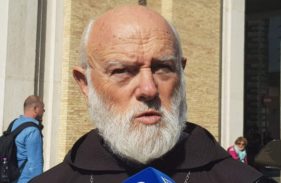

SANTIAGO, Chile (Crux) – When the entire Chilean Bishops’ Conference presented their resignations to Pope Francis in Rome last year amid a massive scandal involving clerical sexual abuse and cover-up, Celestino Aos Braco had been a Bishop of a small diocese for just four years.

As it turns out, it was scant preparation for the job the Pope gave him in March: Apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of Santiago, the capital of Chile and the eye of the local church’s storm.

Santiago is home to two of the country’s most infamous pedophile priests: Fernando Karadima and Cristian Precht, both of whom were expelled from the priesthood last year.

Aos spoke with Crux on May 4, soon after the local church had signed a deal of cooperation with the Chilean prosecutor’s office – a deal that was rescinded by national prosecutor Jorge Abbott a few days afterwards.

Among other things, Aos said that comments from Francis last year about a “culture of cover-up” among the Chilean bishops led to impressions that all prelates in the country were equally guilty, an image he called “painful” and “unfair.”

Aos also discussed why he chose not to give communion to the faithful who wanted to receive it while kneeling down, even though it’s a practice allowed by the Vatican. He also spoke about his meeting with Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston while the two were in Rome in April.

What follows are excerpts of Aos’s conversation with Crux. The first part of that conversation is available here.

Crux: What happened with the signing of an agreement between the Church and the prosecution? Why were survivors of clerical sexual abuse the first to protest?

Aos: The Church is not the only entity that signed this agreement with the prosecution.

It’s not something that was signed overnight. Would it have been possible to give more participation to survivors? Probably. But when an agreement of this sort is prepared, two sides are involved – in this case, the Prosecutor’s Office and the Church.

The agreement didn’t give us privileges. On the contrary, it went beyond what’s required by law today, saying that any abuse someone who works for the Church finds out about outside the confessional has to be reported to the prosecutors.

I saw in the prosecutors a desire and willingness to collaborate. What we want is for the truth to come out in Chile, and for those who are guilty of committing a crime to answer to civil law for what they did. And we want to work with the prosecution so that these crimes never happen again.

In Rome, the Holy Father presented you with a document saying bishops in Chile had destroyed evidence and dismissed complaints. Today there are 10 bishops who’ve been subpoenaed to testify. This week, the bishops gathered for their general assembly. Is there a certain discomfort among you, wondering what the Pope was referring to?

The meetings of the Bishops’ Conference are always scheduled to review how we’re doing as a church. The meeting in Rome to which the Pope called us, and during which he gave us this document [on the situation of the Church in Chile], which had no legal value but was a meditation, included some strong expressions that have caused discomfort among us Chilean bishops and which the Pope himself tried to explain later.

I speak, for example, of a culture of cover-up, which makes it seem like we’ve all been conspiring with one another. He talked about some very hard things, like the destruction of evidence, and here in Chile that raised a lot of dust with the prosecutors.

We don’t know if he meant that the evidence was destroyed in Chile or in Rome, but indeed, if he says so, there must have been cases in which some evidence was destroyed, which is a crime. The problem is that, as it’s all up in the air, many took it to mean that every bishop is guilty of covering up and being willing to destroy evidence.

That has been very painful, and also very unfair. There are some who have acted like this, and that is repugnant, but not everyone has.

We have worked according to what he has indicated, but the Pope doesn’t have a recipe book, he started a process. When you start a process, it is reoriented if necessary. The process has to take into account the problem, which had been badly addressed in some cases. When we spoke with the Pope, he told us that changing a person is not the solution. This is a part of a process that needs short, mid- and long-term planning.

We want to accompany people and be communities that encounter Christ. If we are relating in a way that is not what Christ wants, but with an attitude of arrogance, abuse of the other, something has to change. We have to change the way we relate to each other, to society, and to these people who are suffering because they are victims. Sometimes you have a clear goal, but sometimes you don’t.

Seeing it from the outside, one wonders why bishops whose resignations the Pope accepted are concelebrating with the apostolic administrator at the Chrism Mass during Holy Week …

Even assuming that one has committed a crime, not all are equally grave: we have what’s known as the “proportionality of the penalty.”

Secondly, we should take into account that these people who were concelebrating have not been sanctioned, and therefore they are fully entitled to participate in the Mass. [Perhaps] some Christians don’t happen to think so, [but] it’s precisely on those days of Easter that we as Christians are all called to reconcile with ourselves and those around us.

Was it unfair of Pope Francis to put all of the Chilean bishops in the same bag, talking about a culture of cover-up?

Some say that the Pope was unfair to put us in the same bag. I say yes and no. Because when I apologize for a crime as atrocious as abortion, I have not aborted or participated in an abortion, but I’m in solidarity with those who have and beg forgiveness for it.

So the Pope had the right, in what was a meditation with no actual legal value, to bring us to the awareness that we are all responsible for this. When it comes to abuse, one cannot say, ‘I take responsibility for what happens in my diocese, and only that’, or, ‘I don’t have cases in my diocese so it’s not my problem.’

No, he invited us to say, ‘I take responsibility for all of this evil, how can I help?’ That is the orientation that the Pope gave us, and I think it’s what we have.

You have a difficult job, yet on Holy Thursday we saw you making it perhaps even harder, asking that people stand up to receive communion rather than kneeling. A week later, you were in a video where you’re seen giving Communion to everyone, including those kneeling. Why?

Some say that I denied them Communion, but I didn’t deny Communion to anyone. There was a person who got on his knees, I asked him to get up, and I gave him Communion. But then to a second person, who did not want to get up, when he got up, I offered him Communion and he did not want it.

What was the criterion for making them stand up to receive communion?

Communion is not simply a union with God but with the community. There is a Spanish saying that says: ‘Where you are going, do whatever you see.’

If I go to a place where everyone receives Communion on their knees, I do so too. And if everyone goes to Communion standing up, this is normal too. A week later, as I celebrated Mass in the Sanctuary of Mercy, there were some who received Communion on their feet, others on their knees, it was given to all.

I believe that Jesus Christ is in the Holy Host, whether I’m standing or kneeling. At that time there was a reaction, some said I humiliated [these people] by asking them to get up. If they felt humiliated, I ask forgiveness, it was not the intent. But despite this incident, I’m calm.

There are people in Valparaíso, a diocese where you served as promoter of justice, who had a negative experience with you and said so when you were appointed to Santiago.

There are two people whose case I evaluated as a promoter of justice. Everyone in a court has a role. I was the promoter of justice. I exercised my role, but it’s not for me to give a sentence. And there’s a detailed registry of what I did in each case. The two people were offered to file a complaint, and they did.

They can agree with what was done or not, but what had to be done, was done.

Anything else you want to say?

Only at this time [in history] we have a moment of great suffering in the Church, but the Church is beautiful. And this is something the Pope has always insisted on: there are so many good people, so many people who are sanctified.

There is so much goodness in the world, but that is the tragedy of our time: the good news doesn’t make noise. The press itself is stuck in this idea, and this is a challenge.

Do you feel supported by the Holy Father?

I feel supported, but I am hoping that he’ll support me even more: I’m waiting for him to name some auxiliary bishops, because I have one who’s helping us with prayer, but is too sick to take on any pastoral tasks, and that leaves only one, Bishop Cristian Roncagliolo, but that’s not nearly enough.

[Four of Santiago’s auxiliary bishops were appointed by Francis as apostolic administrators of other Chilean dioceses grappling with the fallout of the clerical sexual abuse crisis].Tell us about meeting Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston, who like you is a Capuchin, and also head of the Pope’s Commission for the Protection of Minors, when you were in Rome.

I had to meet with him. I ran into him on the street, and he invited me to have lunch at Santa Marta [the residence on Vatican grounds where Pope Francis lives and where most cardinals stay when visiting Rome.]

I told him we need his help, because he’s one of these men who’s had to address a crisis like this before. Not because we’re going to do the exact same thing, but because we need help. The damage and suffering don’t affect only the direct victims [of clerical sexual abuse], but also many priests, and many communities led by men who shouldn’t have been priests in the first place.

There’s also the fact that many today insult us and the faithful for continuing to be Catholic against all odds.

O’Malley is a man who can help us and is willing to do it. My intention is to invite him to Santiago and the rest of Chile, so that the people, the priests, can talk to him, because we have a lot of work still left to do.