Efforts to combat America’s opioid crisis are poised to be at the forefront of the nation’s priorities in this new year.

More than two million Americans were addicted to prescription or illicit opioids in 2016, and the latest data show there were more than 63,600 drug overdose deaths that year, most involving opioids, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

These figures – and the devastating impact these drugs are having in communities and families across the nation – have compelled federal and state governments to raise awareness to combat the problem.

Last October, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a national public health emergency, and earlier last year, New York City launched its HealingNYC initiative to reduce opioid overdose deaths by 35 percent in the next five years.

Opioids are painkillers that also produce a euphoric effect. Common ones include prescription medicines like morphine, codeine, Oxycontin, Vicodin and Fentanyl, and illegal substances like heroin.

Prescription opioids have become the drug of choice for so many Americans across all demographics and age groups largely because of their accessibility.

“Most of these addiction disorders have started just from going to the doctor and having some medication prescribed to avoid or minimize pain. That has been the root of the opioid crisis,” said Claudia Salazar, who serves as vice president of clinics, recovery and rehabilitative services for Catholic Charities Brooklyn and Queens.

Low-dose approaches to pain management are being adopted by some doctors in the wake of the crisis, and every state has some type of prescription drug monitoring program in place.

Increased Hospitalizations, Overdoses

In Brooklyn and Queens, prescription drug addiction is not as prevalent right now as it is in Staten Island and Long Island, Salazar said, “but we are starting to see an increase in hospitalizations and overdoses, and it’s very alarming in the age group that it’s happening to.

“We’re starting to see children overdosing or not being able to function because they’ve taken their parents’ medication – prescription medication.”

Most Americans get prescription drugs at some point for an extracted tooth, chronic pain or minor surgery. For young people who can access the family medicine cabinet, these pills are free and available for the taking.

Most Americans get prescription drugs at some point for an extracted tooth, chronic pain or minor surgery. For young people who can access the family medicine cabinet, these pills are free and available for the taking.

“They’re not smoking weed or snorting something so they can easily take it and nobody would notice. They might just be a little off,” Salazar said. “It’s not that visible unless they take a lot.”

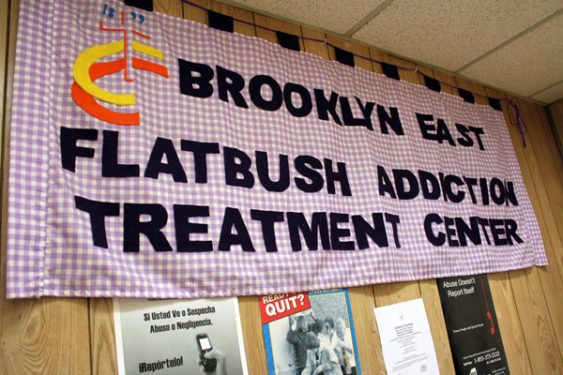

Catholic Charities recently launched an adolescent treatment program for youth, age 12 to 17, who are taking or addicted to drugs or alcohol at its Flatbush Addiction Treatment Center, which provides outpatient clinic and rehab services.

“The Department of Health reached out to us and asked us if we were interested in running an adolescent program for substance use and we’re very excited about it,” Salazar said, noting that the program is the first of its kind in Brooklyn.

Teens are referred for treatment through their schools, primary care doctors, hospitals and the justice system, and are required to attend programs at the center at least three times a week.

“It’s a tough age to begin with,” Salazar said. “To have them commit to coming in for treatment, and acknowledge they have a problem, it’s very challenging.”

Being able to connect with this unique age group is vital to treatment, so center staffers have been trained in how to interview and work specifically with teenagers.

“We have a great team here that really can relate to adolescents. We’ve trained them on the language to use, and we run groups, which are more effective than the individual (treatment) model for adolescents.”

Support at home is also a key to recovery. The center works with parents and families to help them understand the nature of addiction; to educate them that it’s a sickness, not a choice, and it can be treated.

“There are so many changes that go on in adolescence,” Salazar said, “so it’s a very challenging condition to acknowledge and diagnose.

“It’s also a very hard thing for parents to accept so sometimes that’s when the denial comes in. You can have someone in the family that has an addiction problem that’s very apparent to everybody, but it’s not spoken about.”

Parents may overlook warning signs like changes in behavior, withdrawal and poor performance in school, attributing those things to ‘just being a teenager.’ Many times, families are only forced to face the issue when the school calls home, the child gets involved in criminal activity or worse, overdoses.

A Treatable Disease

“Our goal is to educate people that addiction is a medical condition, a disease like any other – cancer, diabetes – and that it’s treatable,” Salazar said.

“Often because of the stigma, people do not look at substance use or addiction as a disease. They tend to think, ‘Oh, you have control over it, but you don’t want help, you don’t want to stop.’”

For Norman, 50, a recovering heroin user, stopping was something he could not do on his own, even after losing custody of his daughter.

“I lost a lot of respect for myself,” he said. “It’s easy to get hooked, but it’s hard to not be.”

A friend introduced him to the drug, which gradually became “a way of escaping” his everyday problems – and the cause of many more with his family, his children and girlfriend.

An accident while he was high finally landed him in the hospital, followed by rehab, but that is what he needed to stop using heroin and start rebuilding his life.

Drug free for 15 months, Norman is grateful for the support and outpatient services he’s found at Catholic Charities’ Jamaica Behavioral Health Center.

From day one, he said, “They’ve had open arms. The people are nice. It’s like, ‘Let’s get you better. Let’s make sure everything is right for you.’ It’s more like family.”

He goes to the center every week for one-on-one sessions, which he prefers to group therapy, and his therapist is available any time he needs to talk.

“Since I’ve been off heroin, I have a new outlook on life,” he said, explaining that his therapist has taught him healthy ways to cope with life’s up and downs so he’s less inclined to look for an escape.

“I’ve seen so many good things happen for me,” he said. “A lot of the things I lost, I’ve gained back and I got to see what’s worth fighting for.”

First and foremost is his daughter, whom he hopes to bring home soon.

“I take it one day at a time,” Norman said. “I gotta keep looking forward because God didn’t make us to walk backward.”

His advice to others struggling with opioid addictions, especially teenagers: “Don’t let the disease fool you. You’re better than the disease. … Take the help that’s out there.”

Catholic Charities hopes to expand its adolescent program later this year to Brooklyn public schools where the agency already has mental health satellites. The agency also hopes to partner with parishes to reach teens and families in every community.