CENTRAL PARK — Many New Yorkers can attest to the countless hidden gems scattered throughout the city. One

destination in particular, although not still standing, lives on as a poignant symbol of resilience and community in African American history — Seneca Village.

Thanks to ongoing preservation efforts, people can tour the former site of what was once one of the largest communities of free African American property owners in pre-Civil War New York before it was demolished to make way for Central Park.

The tour begins on West 85th Street, where participants learned about the village’s founder, Andrew Williams, who purchased the land between 81st and 85th Streets from John and Elizabeth Whitehead two years before slavery was abolished in New York in 1825.

“John and Elizabeth Whitehead were selling land exclusively to black people,” Central Park Conservancy guide Desiree Rodriguez St-Plice said. “We now describe them in history as abolitionists, but we don’t know why they were

doing this.”

Rodriguez St-Plice, the day’s guide, explained that the tour sought to honor the legacy of Seneca Village — its residents, their homes, and their contributions to the fight for freedom and equality — while challenging the “demeaning stereotypes” that the media once used to describe it. She noted that its residents were once described as “poor squatters living in shanties” as part of a smear campaign to demoralize the village, which was also described as violent and unclean.

The tour stopped at the sites of the three churches that once stood on West 85th Street — African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, African Union Church, and All Angels’ Church, a racially integrated church where Irish and African Americans worshiped side by side.

Rodriguez St-Plice spoke about how the churches were “pivotal to the community.”

“Back in the days when slaves were freed, these were the institutions where black folks were getting their resources, they were getting community, they were looking for jobs,” she said. “Clearly, that was not liked by their neighbors. They literally destroyed everything they worked for.”

In the 1800s, Seneca Village had been home to between 50 and 60 families — about 230 people in total — a place where African Americans could turn their dreams of owning land into reality, according to Rodriguez St-Plice.

On the next stop, the group learned the stories of several women landowners, including Sally Wilson, Catherine Hennon, Nancy Moore, and Elizabeth Harding, daughter of Diana Harding, one of the first settlers in the village. This was a rare and powerful achievement for African American women of that era.

Although it is unclear how they acquired the land, Rodriguez St-Plice said it is assumed that they inherited it through family or being widowed. “This is another way Seneca Village was special and unique among its neighborhoods,” she said.

In the 1840s, debates began to rage over the effects of urban growth amid New York City’s population doubling between 1845 and 1855. Advocates for a large public park argued that it would offer New Yorkers a peaceful escape from the city, providing fresh air, nature, and a space to gather.

At first, a privately owned area along the East River was proposed, but critics argued it was too small and too far from

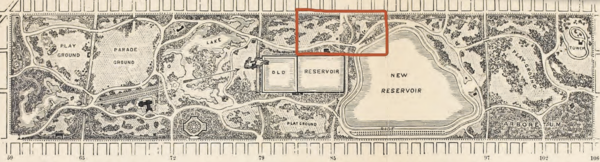

the city center. In response, the city considered a larger tract of land near the Croton Receiving Reservoir located in Seneca Village, which was ultimately selected after nearly three years of debate.

When the city acquired the village land for Central Park in 1857, it used “eminent domain,” which allowed the government to take private property for public use. The city gave residents only two years to move out. Rodriguez St-Plice said the end of Seneca Village came as a shock to all its residents.

While residents were compensated for their land, Rodriguez St-Plice said not all were paid their fair share. Williams, for example, only received half of his property value. The story of Seneca Village is still being pieced back together. It was essentially lost until it was briefly mentioned in a book published in the 1990s, “The Park and the People: A History of Central Park,” sparked interest. It was only nine years ago that archaeologists discovered thousands of artifacts that had been buried for more than 150 years.

The artifacts contributed to creating temporary signs placed in the Seneca Village area of the park to share the community’s history. Officials from the Central Park Conservancy expect these signs to remain in place until October, with plans to replace them with more permanent installations afterward.

Ann Rosenfield, who was visiting from Toronto, said she participated in the tour because she felt a responsibility to learn more about black history following the death of George Floyd in 2020.

She said that early on in her research of the village, she noticed the stereotypes that Rodriguez St-Plice was referring to and realized during the tour that those stereotypes were different from the truth.

“It feels like the opposite of what I read,” Rosenfield said. “These were [people] who sound upper-middle class with two- and three-story homes, educating their children and themselves becoming literate, which would have been less common in those days. “So, I learned a lot,” she added.

Excellent story, with thorough reporting, Alexandra! Very appropriate for a Black History Month edition of The Tablet.

Hope to see more of these stories from you.

Best,

Jim Harney

jtharney3@gmail.com

jharney@desalesmedia.org

917-968-5998