DYKER HEIGHTS — Father Joseph Lin, a native of northwest China, was born in 1974 during the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” — a very grim decade for Catholics, he said.

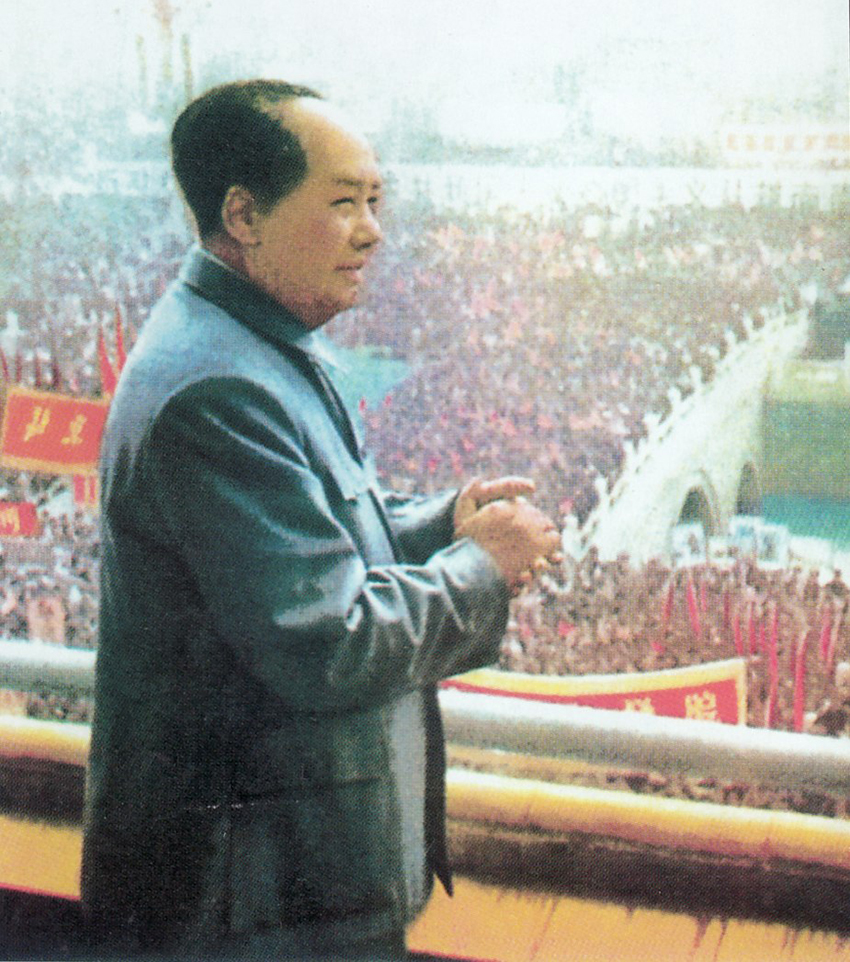

The Cultural Revolution evolved under the rule of Mao Zedong, chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

From 1966 until his death in 1976, he sought to purge the nation of “old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits” — anything that he thought contrary to the Marxist-Leninist ideas that fed his brand of communism — “Maoism.”

The purge escalated with violence carried out by CCP cadres of “Red Guards.”

“From our parents’ (generation), the priests and sisters were in the jail and some of them were in labor camps,” said Father Lin, parochial vicar for the Basilica of Regina Pacis in Dyker Heights. “They burned down the churches.

“There was no public Mass, no catechism, no Eucharist.”

The legacy of Mao to now, however, is full of crackdowns on Roman Catholicism and other religions going back to the Chinese Civil War in the late 1920s. By that time the Church had several centuries of achievements in China.

Growth, Then Terror

Catholics first arrived there in the 8th century during the Tang Dynasty, and missionary priests from Europe — including Dominicans and Franciscans — built their ministries over the next 1,200 years.

At the end of World War II, an estimated 3,080 missionaries and 2,557 native priests served about 4 million Chinese Catholics in 20 archdioceses and 85 dioceses, according to a report from the Roman Curia to Pope Pius XII.

The missionary priest became bishop of Kaying in 1935. During World War II he aided Chinese guerrillas battling Japanese forces and refugees disrupted by the carnage.

Meanwhile, the Chinese Civil War had ensued, off and on, since 1927 with CCP-controlled fighters up against troops loyal to the nationalist Republic of China.

Hostilities intensified after a reprieve during World War II. The communists’ 1949 victory ushered in Mao’s first political ascension.

Next, the CCP targeted Western missionaries — Catholic and Protestant — accusing them of “foreign cultural imperialism.” Many of them fled, but most Catholic priests stayed, including Bishop Ford.

The CCP arrested him in 1951 on espionage charges. He suffered torture and imprisonment, which lead to his death in 1952. He is now Servant of God Bishop Francis X. Ford, a candidate for sainthood.

Mao was sidelined by other party leaders, but he made a comeback to launch his Cultural Revolution.

Hostility Hypothesized

Being a devotee of Marxism, the chairman appropriated a comment from Karl Marx that religion was the “opiate of the masses.”

A closer look into this hostility was offered by the Dalai Lama, the exiled leader of Tibetan Buddhism.

In his 1997 autobiography, he recalled his last meeting with Mao. It was in 1954 during a tour of China, which had annexed Tibet three years earlier.

The Dalai Lama said Mao complimented Buddhism for its care of the people. But later, Mao leaned in close and whispered: “Religion is opium.”

He said the leader further opined that religion had two “great defects: it undermines the race and retards the progress of the country. The chairman told his guest that “Tibet and Mongolia have both been poisoned” by religion.

“I was a little bit shocked, but I just remained calm,” the Dalai Lama told Bloomberg News in 2022. “If Chairman Mao lived a longer period, I do not think he’d still consider religion is opium.”

Cult of Personality

Ironically, Mao himself became a sort of messiah figure during the Cultural Revolution. His image highlighted massive posters, banners, exterior walls of big buildings, and statues.

Everyone, including children, carried their own copies of Mao’s book of quotations, the so-called “Little Red Book” — tantamount to a religious tome.

Meanwhile, Catholics, undeterred by totalitarianism, kept pursuing the faith, albeit secretly.

“The people practiced the faith privately in their homes,” Father Lin said. But they did so at great risk.

For example, Mao reportedly branded the Legion of Mary a counter-revolutionary paramilitary group, so he ordered its Chinese members rounded up and executed.

“In that time, our faith was very strong,” Father Lin said of Chinese Catholics. “It’s true — the more suffering, the stronger the faith.”

Really a Miracle

Ultimately the Cultural Revolution failed to crush the faith nurtured by people like Father Lin’s parents.

“We were very strong because of our parents,” he said.

After Mao died, the Chinese government softened its stance on religion for economic reasons. The leaders sought foreign investment, especially from the U.S.

That could not happen amid full-on religious persecution, Father Lin said.

“That’s really a miracle,” he added. “They wanted to kill all the Catholics, but they could not because of the grace of God, the Holy Spirit.”

Nevertheless, the People’s Republic of China still tries to regulate the Church, particularly in the selection of bishops.

They also announced the first new diocese since Chinese communists took control in 1949.

Details of the agreement have remained secret, which prompted Father Lin and other Chinese priests to view it with a “wait-and-see” approach.

Meanwhile, Catholics who believe the pope is the sole authority of the faith still worship and catechize in “underground” churches.

But Father Lin said he now considers the 2018 agreement as a positive move, as long as the government’s preferred bishops have the pope’s OK.

“Over the history, culture, and the people of China, it is a small step,” Father Lin said. “But I think it’s a big progress for the Church.”