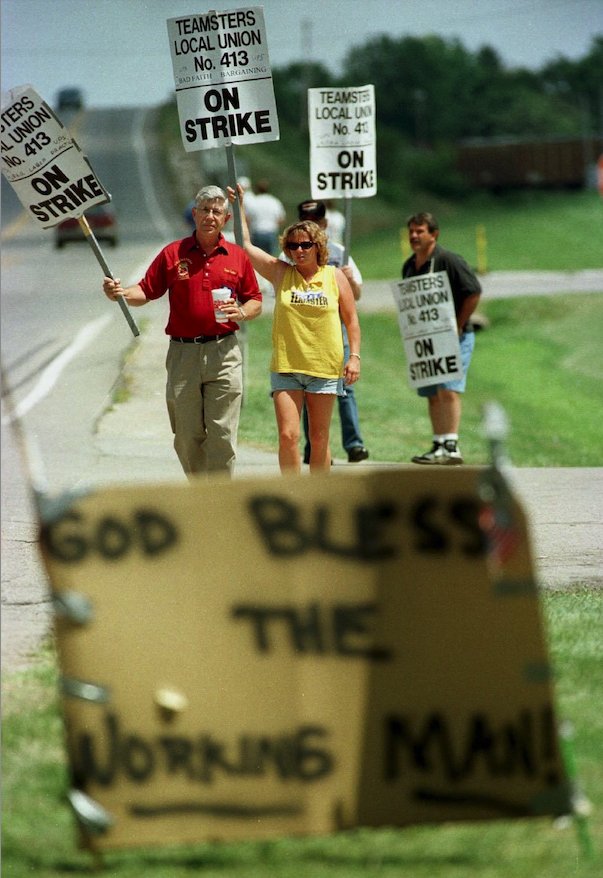

WASHINGTON — Although Hollywood actors and screenwriters currently on strike have made headlines, they’re just one example of workers across the country who have joined together to demand more from their employers this summer.

Starbucks employees, Amazon delivery drivers, educators, and school cafeteria workers, along with hotel, train factory, and brewery employees have all formed picket lines in the past few months. Strikes by UPS employees and pilots from two major airlines were narrowly avoided, but a major strike could happen this fall in a dispute between the United Auto Workers and major American car manufacturers.

The current attention on workers’ rights comes at a time when public support for unions is on the rise. A Gallup survey last year said 71% of Americans approve of unions — which has not been this high since 1965.

And although there have been a number of strikes this year, there are not nearly as many as there were before the 1990s, simply because a smaller percentage of workers are now represented by unions. According to Bloomberg Law, about 10% of all U.S. workers belong to a union and about 323,000 workers have been on strike this year, making it the biggest year for strikes since 2019.

But amid current attention to workers’ rights, not all Catholics know that the Church has something to say about this, said Clayton Sinyai, executive director of the Catholic Labor Network, an association of Catholic union activists that promotes collaboration between Church and labor organizations.

The group issues an annual report on the number of Catholic institutions where at least some employees have union representation.That number was more than 600 last year. It also sponsors an annual Labor Day Mass which will be broadcast on the Catholic Labor Network’s YouTube channel (@catholiclabornetwork7217) at noon ET on Labor Day.

Sinyai, a former rubber worker, railroad clerk, and letter carrier, has spent the past two decades in a variety of union staff roles as a researcher, organizer, and communications director. In an interview with The Tablet, he said, “Most Catholics no longer know the Church has teaching about labor and work.”

An understanding of this starts with Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical “Rerum Novarum,” which was written just after the Industrial Revolution. It specifically addresses conditions of workers and says they have a right to just wages, fair treatment, and to form unions.

The letter also criticized capitalism for its emphasis on wealth and greed and socialism for its rejection of private property and not emphasizing the dignity of each individual.

To Catholics today who might say that message is outdated, Sinyai notes that Pope Benedict XVI’s 2009 encyclical, “Caritas in Veritate,” emphasized that unions are even more important today because of globalization.

Meghan Clark, an associate professor of moral theology at St John’s University in Queens, said that “in large part, Catholic social teaching has an even broader understanding of unions than others” because it not only looks at the idea of workers’ rights but tends to “strongly support those kinds of associations across the board where people are working together for the common good.”

She noted that from her standpoint as a moral theologian, individual strikes can be complicated, based on what the workers are demanding, but “support for unions is not.”

She said Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical on labor came out of the rise of industrialization and worker exploitation, where Church leaders were asking for guidance but Catholics on the ground level were also organizing worker movements. She said his writing “firmly and unapologetically affirmed the rights of workers to unionize and do collective bargaining” while still recognizing that some unions need to be reformed.

Then the next step in Catholic social teaching about workers, she said, stems from the writings of Pope St. John Paul II, where he emphasized that labor should be a priority over capital.

His 1981 encyclical “Labor Exercens,” states: “Workers not only want fair pay, they also want to share in the responsibility and creativity of the very work process. They want to feel that they are working for themselves — an awareness that is smothered in a bureaucratic system where they only feel themselves to be ‘cogs’ in a huge machine moved from above.”

Clark, who mentioned that the faculty at St. John’s are part of a union, said Catholic social teaching supports workers advocating for their rights, but it also sees unions overall as not “just a response to injustice” but as a way for workers to have a voice in “shaping the product of their labor” and the conditions of their work.

“If you think about the writers’ strike in particular,” she said, “part of it is about wages and benefits and part of it is about the legitimate attachment of their creative work, which Catholic social teaching has addressed.”