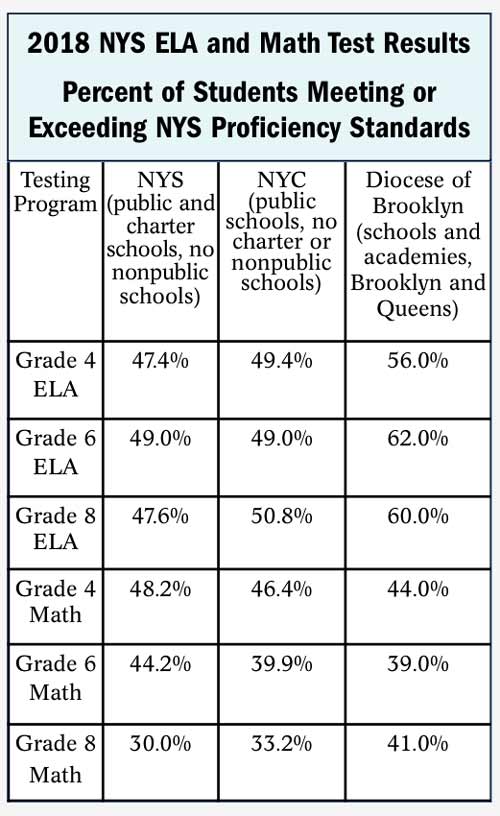

The New York State standardized test results are in – and students in Brooklyn and Queens Catholic elementary schools surpassed their public-school peers in English language arts, while earning comparable scores in math.

The tests were given to fourth, sixth and eighth graders in English language arts (ELA) and math last spring to gauge students’ mastery of Common Core learning standards. The state education department released the score reports this fall.

“I thought the ELA results were great – off the charts great,” said Diane Phelan, associate superintendent for evaluation of programs and students. “We average about a 60 percent proficiency in ELA in all of our grades if you put them together. So we far outperform New York City and New York State.”

Phelan tracks this data from year to year in the diocesan Office of the Superintendent–Catholic School Support Services. But current data cannot be compared to the past because the state redesigned the test. This year, the exam had fewer questions and was given over two days instead of three.

Competitive with City and State

Competitive with City and State

And while diocesan students traditionally perform well in language arts, “the math side is a little different story,” Phelan said. As in the past, she said, “we are competitive with the city and state for sure, but we’re a little lower in grades four and six. That’s been an ongoing issue.”

The superintendent’s office has been working with schools to address that shortcoming with “math coaches, resources in the schools and a lot of professional development for teachers on the math standards,” she said.

Along with students’ scores, diocesan principals and teachers received detailed reports showing specific areas in ELA and math where individual students and whole classes either excelled or needed more instruction. In math, multi-step word problems tended to stump students the most, Phelan said.

Parents were also given a breakdown of their child’s performance level. A student at Level 1 is below proficient, Level 2 is partially proficient, Level 3 is proficient and Level 4 is more than proficient.

“If students fall into Level 1 or 2, they’re eligible for academic intervention services to help get up to par or proficiency. Most schools offer before- or after-school remediation, others do it during the school day in a pullout in a resource room setting.”

Phelan urges principals and teachers to learn from instructional reports – which have actual test questions and students’ responses – to pinpoint both classroom and individual students’ weaknesses.

“Once they start looking at these reports, they really get into them because there’s all sorts of item analysis. You can see what percentage of your class chose A, B, C or D for an answer,” she said.

Working Together to Achieve Success

Phelan feels there should be a conversation among teachers across the grades, not to point fingers, but to figure out why students are weak in a particular area. “It’s not the blame game or who taught it wrong. It’s about the fact that we’re all in this together to educate the whole child,” Phelan said.

“We serve the needs of a lot of different students. Students come to us with all different needs so teachers look at test scores and differentiate instruction to fit the needs of students.”

EngageNY.org, the New York State Education Department website, provides resources that teachers – and even parents – can use to familiarize students with practice test questions on every level.

Phelan also noted that the test refusal rate in public schools was 18 percent, compared to just below 2 percent for the diocese. And English language learners also had the option of taking the math exam in their native tongue. After English, the five languages in which the math exam was given in the diocese were Korean, Russian, Spanish, Haitian Creole and Chinese.

Among the diverse student body at Queen of the Rosary Catholic Academy, Williamsburg, math scores have been improving according to James Anthony Daino, principal, who has been on a mission to make his students and teachers love math as much as he does.

“Math is something amazing. It’s something I want kids to love and enjoy,” said Daino. That love begins with the teachers and so he brings math and technology coaches into the classrooms, fosters team building among faculty and even pops into classes to teach lessons himself. He also encourages teachers to use online math tools like Mathletics, Khan Academy and EngageNY, in their lessons.

After-school and Saturday morning test prep programs in math are measures that will be added in the coming months.

Daino said he struggled in reading in school so math became his comfort zone. He found confidence there until his reading skills improved.

In his school, 78 percent of students read at grade level – his goal is to have them up to 88 percent by June – and students statistically perform higher in ELA. He’s also implementing programs from nursery through grade eight to get students in the habit of writing, self-evaluating and editing their work. Upper grades are even writing research papers.

Keeping Expectations High

“Our children are not just numbers. We truly want to know who the child is,” he said, and that means understanding their particular challenges. “We have children of all different learning styles and needs, whomever God sends us. We keep expectations high … and we give them the education they need,” he said.

Like Daino, Daysi Munoz, who teaches third- and fourth-grade math at Notre Dame Catholic Academy, Ridgewood, also loves teaching math – but admits she used to hate it.

“At first, math was scary for me so I understand my students’ fears when I introduce a new topic,” she said.

To address her students’ weaknesses, particularly with word problems, she’s created a Math Word Wall in her classroom with terms that students need to know, and a step-by-step strategy to break down and better understand the questions.

She supplements class lessons with online resources, including educational games offered through Mathletics and EducationCity.

“It’s teaching them and they’re having fun at the same time,” said Munoz.

She also runs an afterschool math club to prep students for state exams and spends some lunch periods giving one-on-one instruction to students who need more help.

And while diocesan students may struggle with math in fourth and sixth grades, Phelan pointed out that by eighth grade they’re back on track; the eighth-grade math results showed diocesan students surpassed peers in the city and state.

“In the lower grades, teachers are generalists. But when you get to sixth, seventh and eighth grade, that’s where our certified math teachers are, and we get stronger as we go up the line,” Phelan said.

“My theory has always been that the longer the kids stay with us, the better they do because our teachers are very good at seeing where the strengths and weaknesses lie,” she said.