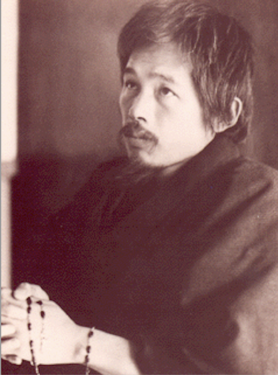

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass. — Dr. Takashi Nagai, the dean of radiology at the Nagasaki Medical College Hospital, was preparing for class on Aug. 9, 1945, when the U.S. dropped the “Fat Man” atomic bomb.

“Before my eyes, the flash of blinding light took place,” Nagai wrote in his 1949 account of the experience, titled “The Bells of Nagasaki.” “The glass of the windows smashed in, and a frightening blast of wind swept me off my feet into the air. … It was as if a huge, invisible fist had gone wild and smashed everything in the room.

“I felt that the end had come.”

Nagai, a convert to the Catholic faith, survived the blast despite a head wound. But an estimated 80,000 people perished, including his wife, Midori.

The Urakami Cathedral in Nagasaki, Nagai’s parish, crumbled. One of its two bells escaped destruction, but not the other.

Now, the St. Kateri Institute, a lay apostolate in Williamstown, Massachusetts, has raised around $39,000 to buy a new bell. However, $17,000 more is needed to finish the work at a St. Louis foundry, transport the bell to Nagasaki, and install it.

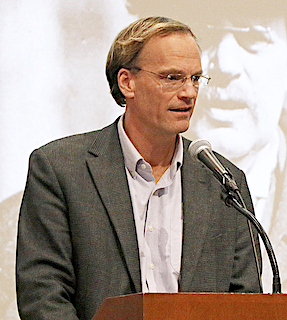

James Nolan, president of the institute, said the goal is to complete everything by Aug. 9, 2025 — the 80th anniversary of the attack.

‘Utter Devastation’

Nolan’s fascination with Nagasaki stems from the wartime experiences of his grandfather, Dr. James F. Nolan, chief medical officer for the “Manhattan Project,” which developed the atomic weapons used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nolan described how his grandfather, a U.S. Army Medical Corps captain, was recruited by Manhattan Project director J. Robert Oppenheimer to establish a hospital for the compound at Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Capt. Nolan also developed safety protocols to avoid dangerous radiation and accompanied the core uranium to Tinian — a Northern Marianas island in the Pacific from which the United States launched the atomic bomb attacks. Afterward, he was deployed to Nagasaki to assess the situation and report on the aftermath.

Typical of his generation, he avoided sharing his war stories with family. According to Nolan, his only comment was: “It was utter devastation of the kind you can’t even imagine.”

But 12 years ago, Nolan’s mother gave him a box of his grandfather’s papers, photos, and other artifacts from the Manhattan Project.

“It was a treasure trove of information that really launched my own investigations into the story,” Nolan said.

Atomic Doctors

In “Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age,” Nolan explores how his grandfather and colleagues struggled to balance their zeal for victory with their passion for protecting human life.

During the research, Nolan found the writings of Dr. Nagai, who, before the attack, contracted leukemia — a fatal consequence of working in radiology.

Still, Nagai authored over a dozen books in the six years between the attack and his death in 1951. In “The Bells of Nagasaki,” Nagai offers his “blinding light” and “invisible fist” descriptions of the blast.

Cradle of Christianity

Nagai also describes how the bomb was detonated above the Urakami Cathedral.

Nagasaki, Nolan explained, was known to be the cradle to Christianity in Japan, despite religious persecutions in the 1600s that created the Hidden Christians — who worshiped underground for 250 years until religious freedom returned in the mid-1800s.

Subtle persecution emerged during World War II because Christianity was a religion among the Allied nations, Nolan said.

“They took grief for being Catholic because it’s the face of the enemy, and then that enemy drops the bomb on the center of Catholicism in Japan,” Nolan said. “Japanese Catholics recognize that irony. They talk about it.”

Nolan recalled one such conversation with a descendant of the Hidden Christians, who said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if some American Catholics gave us that other bell?’ ” That conversation inspired the Nagasaki Bell Project.

‘Dawn Has Come’

Archbishop Peter Nakamura of Nagasaki has praised the project for unifying Catholics in Japan and the United States to seek God’s forgiveness, reconcile, and pursue peace.

“The church bell is the sound of the Church’s prayer,” Archbishop Nakamura said in a statement to The Tablet, adding it would be “a great joy” to hear two bells sounding together “as they did before the bombing.”

Nagai felt that joy just four months after the attack when friends retrieved the unscathed bell from the rubble. They rang it on Christmas.

“Bong! Bong! Bong!” Nagai wrote. “The clear sound … ringing out the message of peace and blessings.

“The Angelus from the ruined cathedral, echoing across the atomic wilderness and telling us that dawn has come.”

To learn more about the Nagasaki Bell Project and the St. Kateri Institute, visit: stkateriinstitute.org