WINDSOR TERRACE — Imagine you’re looking to buy an unusual crucifix. You log in to a popular e-commerce site, like eBay. Suddenly, thousands of crosses fill the screen, from ornate jewelry to wooden crafts. Scrolling reveals some items listed as “antique” or “vintage.” There are pectoral crosses worn by bishops. Prices range from just under $10 to $50,000.

Now you’re really curious, so you click on “Religion & Spirituality,” then “Christianity.” This heading lists medals, rosaries, holy cards, and even relics.

Wait, relics? As in first-class relics of saints?

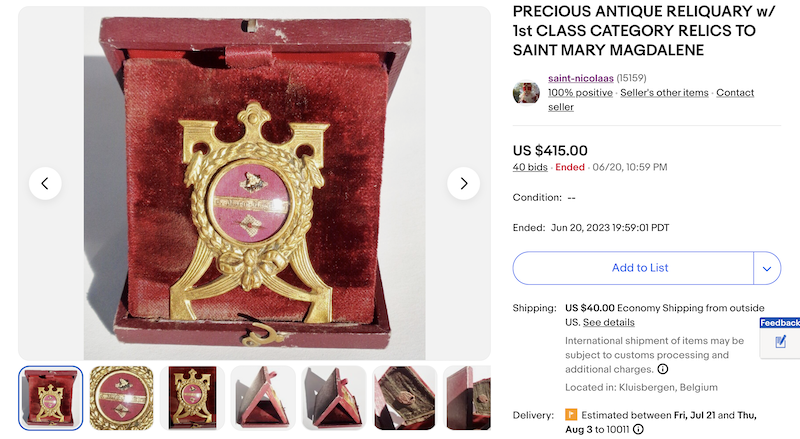

You’d be surprised. Take, for example, this eBay auction item: “Precious Antique Reliquary w/1st Class Category relics to Saint Mary Magdalene (hairs and particle of bone).”

Bidding started at $19.99.

“The whole thing is pretty seedy when you start to sell these,” said Thomas Serafin, founder and president of the Apostolate for Holy Relics. “Because now you’re taking advantage of somebody’s faith.”

Since the 1990s, this apostolate — based in Harwinton, Connecticut — has tried to encourage the preservation of relics for veneration, while discouraging their commercial exploitation.

Catholics are already commanded by canon law not to participate in this sort of commerce. According to the law, “It is absolutely forbidden to sell sacred relics.”

This tersely worded rule appears in Book IV, “Function of the Church,” under the heading, “The Veneration of the Saints, Sacred Images, and Relics.”

Still, the internet yields countless sacred items for auction or direct sale, and not just on eBay. Just plug in “Relics of saints for sale” into a search engine.

Behold thousands of listings from other e-commerce sites like 1stdibs.com and Etsy, plus the online dealers Fluminalis (the Netherlands) and Russian Store (Boston), to name a few.

The sheer volume of listings confirms that relics, both authentic and frauds, fuel a powerful market with fierce competition.

Consider the aforementioned reliquary with first-class relics of St. Mary Magdalene. Now, if someone wants to get in on this bidding, it’s too late. According to the listing, seven people made 40 bids.

The winner paid $415, plus $40 economy shipping from outside the U.S.

Serafin started the nonprofit apostolate with the aim of “rescuing” relics from commercial exploitation. Failures and successes ensued.

“We really had no way to stop them,” Serafin said. “So what happened was other concerned Catholics went out to rescue relics by purchasing them. But we found that these Catholics, not knowing any better, were bidding against each other.”

Instead, Serafin’s group learned to request donations of relics. The apostolate is now responsible for more than 1,200 of them.

But, Serafin noted, neither he nor his organization are “owners.” Rather, he said, the apostolate has “guardianship” of the items.

The relics with certificates of authenticity are available for public veneration.

Relic rescuers also petitioned e-commerce companies to implement policies regarding language used to describe relics for sale, Serafin said.

The Tablet contacted eBay for comment, but representatives did not respond before press time.

To see the company’s policy, load a search engine with these words: “Human body parts policy – eBay.” It states that selling anything considered a body is illegal, which is true.

Serafin noted, however, that relic sellers still manage to profit via e-commerce. “All they started doing was saying, ‘We’re not selling you a relic, we’re selling a reliquary,’ ” he said. “But the reliquary is of no importance in comparison to the actual relic.”

For example, the St. Mary Magdalene reliquary contained this notice: “As per eBay policy, this reliquary does not contain human remains, but only objects of devotions. Relic is free, only the container is on sale.”

Serafin laments that relics become available for public sale, because at some point, they were released, or stolen, from a parish, convent, monastery, or chapel.

Msgr. John Bracken oversees the storage of church furnishings as director of patrimony for the Diocese of Brooklyn. He explained that when a parish is closed or consolidated, the relics it has must be turned over to the chancellor of the diocese.

Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Williamsburg, for example, has guardianship of several relics and has displayed others from outside the parish.

Msgr. Jamie Gigantiello, pastor of Our Lady of Mount Carmel and vicar for development for the diocese, suggested that people work through their parish leadership to arrange visits of relics to view publicly.

“The parish priest is going to get them through the proper channels,” Msgr. Gigantiello said. “That way you get a relic that is authentic, that’s real.

“When you go online, there’s all these imposters out there who will try to fudge anything.”

Vatican Ensures Authenticity of Saintly Relics

The Roman Catholic Church goes through a lengthy process — one that can take hundreds or even thousands of years — to canonize a saint.

Likewise, it goes through great lengths to ensure the authenticity of a relic from a candidate for sainthood, or an actual saint.

First, it helps to know the Vatican makes distinctions between three kinds of relics.

A first-class relic is the body, or any part of it, such as a lock of hair from Blessed Carlo Acutis.

Second-class relics are objects “sanctified by close contact,” like the bandages that wrapped the stigmata of St. Padre Pio.

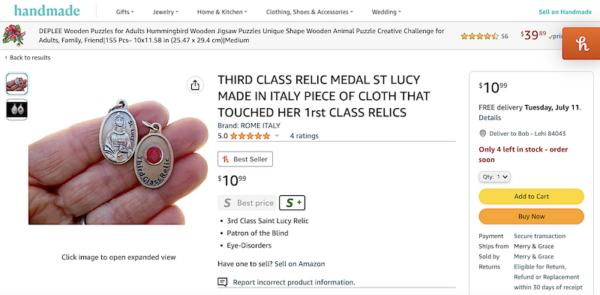

Third-class relics are objects, such as clothes, that touched a first- or second-class relic.

The process for certifying the authenticity of relics is outlined in the Church’s canon law.

First, the petitioners supporting a person’s cause for canonization, such as a guild, select a “postulator” to act on their behalf — similar to a lawyer in a legal proceeding.

Next, the bishop of the diocese where the candidate for sainthood is buried leads a tribunal of four key people.

They include himself, or a designated representative; a “promoter of justice,” whose office was formerly called the “devil’s advocate”; a notary, who documents the tribunal’s proceedings; and a medical professional specializing in anatomical medicine.

The tribunal confirms that the person promoted for beatification does in fact occupy a particular gravesite. It’s an easy task if the grave is well-known or marked, like the saints canonized in recent years. This is hard to do if the person died centuries ago or the grave’s location is unclear.

The tribunal eventually enters the grave or tomb of the person being promoted for beatification. An investigation ensues to determine whether there are relics worthy of a certificate of authenticity.

At this time, relics or the human remains are placed on a table covered with a draping so that the anatomical experts can clean them of dust and other impurities for closer inspection.

Such experts can be licensed medical examiners. Their job is to identify all the body parts in detail, and report their findings.

Also BEWARE of saintsrelics.com!!! They obviously relabel relics and reliquaries and scam people. Beware! https://www.reddit.com/r/OrthodoxChristianity/comments/1pyyk2w/question_about_possible_reidentification_of/