FLATBUSH — Father Lucon Rigaud recently traveled to his hometown in Haiti, but he did not experience any of the gang violence that roils the troubled Caribbean country’s capital, Port-au-Prince.

Still, while no one shot at him, he experienced the chaos differently.

Roadblocks manned by armed, gang-affiliated thugs throttle the flow of vital goods and services from the capital city. Consequently, people can’t buy food because banks can’t replenish cash. Meanwhile, hospitals lack life-saving medical supplies, like portable oxygen tanks.

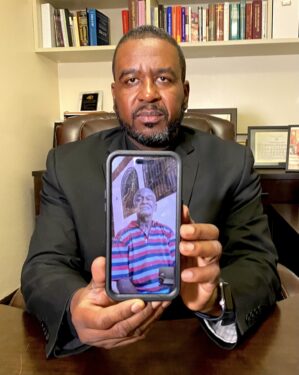

Cyril Rigaud, the priest’s 79-year-old father, became short of breath in February. But his family struggled to find a hospital or clinic with the means to treat him.

“They were finally able to get him the oxygen that he needed, but he wasn’t able to recover,” Father Rigaud said. “In Haiti right now, people are dying, right and left, because of lack of care. And my father was one of those people.”

Father Rigaud, ordained in 2013 for the Diocese of Brooklyn, is now the pastor of Our Lady of Miracles Parish in Canarsie. While visiting Haiti in February and March, he was still pastor of Holy Innocents Church and Our Lady of Refuge Church in Flatbush.

His return to his hometown, Les Cayes, on Feb. 17 was to celebrate his father’s funeral Mass.

“My father, I call him a gentleman,” the pastor said. “He was a good farmer. Up until his last breath, he was a hard worker.”

Father Rigaud said his father did not have much of an education.

“But he believed education was the only way for people who are not upper class to find a way out, and live life with dignity and respect,” Father Rigaud said.

Thus, the priest said, all his siblings are highly educated. One brother is a judge, another is an engineer, and his sister is a teacher. Father Rigaud is also a certified mental health counselor.

He said he didn’t have to work on the family farm, yet he loved helping his father in the fields, planting, harvesting, and driving tractors.

But that was in more peaceful times. During Haiti’s recent gang-fueled turmoil, Catholic priests and religious sisters have been kidnapped for ransom.

In February, an explosion inflicted severe burns to Haitian Bishop Pierre-André Dumas, who was taken to a Miami-area hospital for treatment. Authorities have not yet determined if the explosion was an accident or intentionally set.

Father Rigaud said his family urged him to stay in Brooklyn during his father’s illness and death, but he felt he had to come home. “I had no choice,” he explained “It was the better way for me to have closure.”

He wound up staying much longer than anticipated.

The gang violence focused on government institutions, including police stations and prisons. A massive, gang-engineered jailbreak freed 4,000 prisoners, adding to the chaos.

Meanwhile, gangs locked down Toussaint Louverture International Airport in Port-au-Prince, reportedly to keep widely unpopular Prime Minister Ariel Henry from returning from trips abroad. Henry resigned from office on March 11. But the ongoing chaos kept Father Rigaud from reaching Port-au-Prince, and leaving the country.

Normally, he said, the journey back to Brooklyn is done in a day. It takes a few hours to drive between Les Cayes and the capital, but in-country air service saves time. From Port-au-Prince, it’s a three-hour flight to New York City. This time, however, Father Rigaud’s return journey took three days.

With the airport in Port-au-Prince closed and roads to it impassable, he traveled by land east, across Haiti’s southern coast, to Jacmel, and on to the border with the Dominican Republic.

Father Rigaud is a naturalized U.S. citizen, so unlike fellow Haitians who are kept from crossing the border, he entered at Pedernales with his American passport.

His journey continued to the capital city, Santo Domingo, where he caught a flight to Newark Liberty International Airport.

“It was a very stressful situation that added to the loss of my father,” he said. “I was so upset, the way he died.”

Father Rigaud said he managed his parish via Zoom while stuck in Haiti. Meanwhile, the parishioners prayed for his safe return. He arrived in Brooklyn just in time for Holy Week and Easter.

He declared there is hope for Haiti, even while its people suffer.

The quickest way to stem the violence, he added, is to keep guns and ammunition from reaching the gangs. For example, federal agents in Florida recently intercepted crates of guns destined for Haiti.

“I will say this — things cannot be like that forever,” the priest said. “Haiti is a country where people are good believers in God. And for those who believe in God, there is always hope, even when everything seems hopeless.

“God can always make possible what seems to be impossible.”