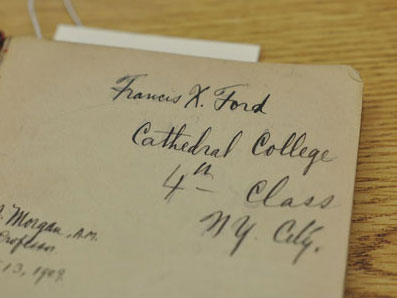

While an observance of the 100th anniversary of the ordination to the priesthood of the late Bishop Francis X. Ford, M.M., was being celebrated, his colleagues at Maryknoll were excited about the prospects of his being canonized a saint.

While an observance of the 100th anniversary of the ordination to the priesthood of the late Bishop Francis X. Ford, M.M., was being celebrated, his colleagues at Maryknoll were excited about the prospects of his being canonized a saint.

“I think it will happen,” said Father Raymond Finch, the Brooklyn-born Superior General of Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers. “I think it will happen in the not terribly too distant future.”

“Of course he should be a saint. I have no question about it,” added Sister Betty Ann Maheu, M.M. “He had all the qualities that would be expected from one who is extensive in virtue. I would canonize him right away. He died a martyr for what he believed.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised,” said Maryknoll historian Father Michael Walsh. “People have been clamoring for his canonization since he died.”

Bishop Ford, who was born in Brooklyn and became the first seminarian to enter Maryknoll, died in a Communist Chinese prison camp in February of 1952. He had been charged with espionage when the Communists took over China.

‘Not a Spy’

“He was not a spy of the United States government,” said Father Walsh. “He was opposed to the Communists and he would work against them.

“People were starting to be arrested. He was concerned about his priests, the religious, and his people.”

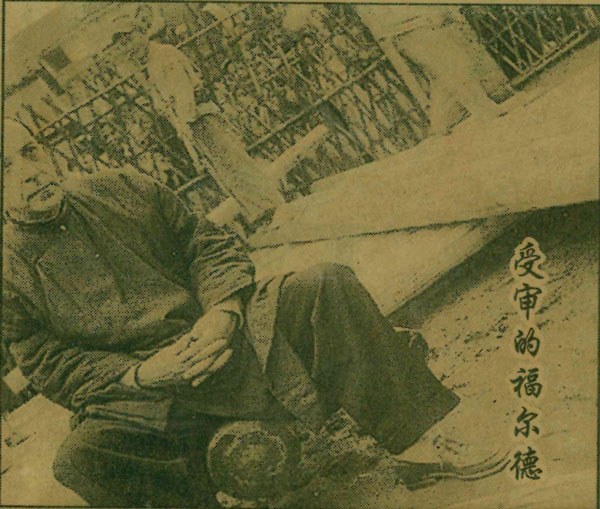

When Bishop Ford did not volunteer to leave the country, he was reportedly dragged from his residence, marched through the streets of several towns, publicly humiliated and thrown into a prison camp at Canton.

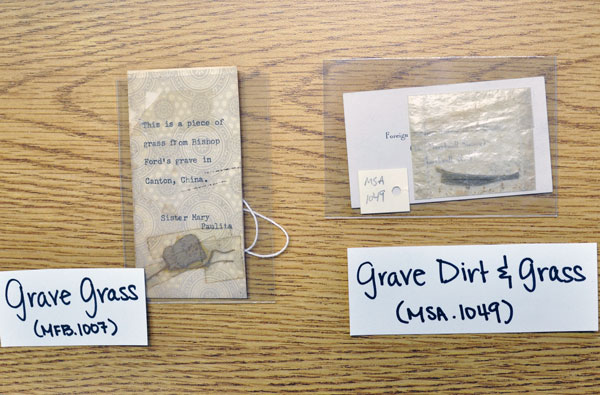

“The government wanted to be the ruler of everything,” recalled 103-year-old Sister Paulita, M.M., one of two surviving sisters who worked with Bishop Ford. “The government didn’t like that we were so closely involved with the people. They worked to control everything.”

Sister Paulita, who endured two years of house arrest before being expelled from China, today lives in the sisters’ nursing home at Maryknoll headquarters in Ossining, N.Y. Still feisty and willing to speak about her experiences, she explained that Bishop Ford was “always very understanding whenever we would go to him with a problem. He was exceedingly understanding.”

Sister Paulita, who endured two years of house arrest before being expelled from China, today lives in the sisters’ nursing home at Maryknoll headquarters in Ossining, N.Y. Still feisty and willing to speak about her experiences, she explained that Bishop Ford was “always very understanding whenever we would go to him with a problem. He was exceedingly understanding.”

She said that the bishop started a catechist school and was responsible for bringing doctors and nurses directly to the people. He was insistent that missionaries be immersed in the culture of the people and understood the language.

“Language was very important to him,” she said. “You had to understand the language in order to express the truth.”

‘The Classic Missionary’

“He is the classic missionary,” said Father Finch. “He’s the guy we all follow. He stayed even when it got dangerous. He stayed with his flock and gave his life for them.

“He was an innovator. He helped the Catholic Church enter into the Chinese culture. The churches he built were in Chinese styles, not Western, which was unusual for the time. He was trying to help the Church be as Chinese as possible.

“He relied heavily on Maryknoll sisters. He was the first to send them out two-by-two.”

Father Finch explained that learning about Bishop Ford at the diocesan high school named for him in Brooklyn was instrumental in his deciding to join Maryknoll.

Sister Betty Ann said that allowing sisters to go out by themselves was a revolutionary missionary practice at the time and had to be approved by the Vatican.

“It was totally new,” she said. “It meant that the sisters could go away from the convent for as much as two weeks at a time.”

It had been determined that if evangelization was going to be successful, it was the women in the villages who needed to learn about the faith. Culturally, it was only other women who could have been with the women in the villages while the men labored in the fields.

She said that Bishop Ford changed the practice of residing in a compound and having people come to them.

“He reversed that and said we will go to the people,” she said.

“He had great trust in people. He welcomed anyone who would come along. People knew they could trust him. He listened to what people had to say. The sisters idolized him.”

Father Finch said that Bishop Ford is still remembered by the Chinese people, especially in the area around Kaying, where he was bishop.

Treated Harshly in Captivity

Bishop Ford reportedly was treated harshly in prison. His health, which was not good when he was detained, deteriorated rapidly. When last seen, he was said to be emaciated and was being carried over the shoulder by a prison guard.

After his death, his body was taken away. Its location today is unclear. For some time, there was a marker at a place of burial but that site has since become a public highway.

After 1952, almost all Christian missionaries were expelled by the Communist government from

mainland China. In fact, when the country reopened itself to the outside world in the 1970s, many were surprised to see that the Church has survived as well as it did in many places. It was attributed to the strong missionary work of communities such as Maryknoll and individuals like Bishop Ford.

Remnants of the persecuted Church remain today as what has come to be known as the Underground Church which exists side by side with the official Patriotic Church, which requires registration with the government.

“They’ve both been loyal,” said Sister Betty Anne. “The Church is trying to reconcile these groups so that the Church can be strong. If the Church remains divided, the Church will be weak and that would be to the advantage of the government.”

Despite a new wave of restricting religious practices, the official government position is that no one is persecuted because of their faith, only for breaking the law by not registering with the government.

Father Walsh said that Bishop Ford’s name continues to be revered among the Chinese. Should he become a saint, “The Chinese Catholics would be proud of that… the powers that be less so.”

Great story … THANKS for publishing it !!