By Jem Sullivan

This spring, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., hosts “Della Robbia: Sculpting With Color in Renaissance Florence,” a rare exhibit of some 40 works of painted terracotta sculpture, mostly the creation of three generations of the renowned della Robbia family of artists.

Groundbreaking in their day, their signature large white relief figures set against a sky-blue background framed by garlands of fruit, flowers and animals in vibrant hues of green, yellow and purple, now come together for the first time in a major American exhibition.

From now until June 4, visitors to the National Gallery can step back into the Renaissance to marvel at the unmatched craftsmanship of this artistic family whose works decorated Florence, birthplace of the Italian Renaissance.

This must-see exhibit, which opened Feb. 5 and is free to the public, also allows visitors to make a visual retreat during the Lenten and Easter seasons with evocative devotional sculptures depicting the Pieta, the Resurrection, the Visitation, the virtues, the saints and many tender scenes of the Madonna and Christ Child. (Those unable to visit the gallery in person can see the works at https://tinyurl.com/jkmm4jd).

Breathing life into clay, Luca della Robbia (1399/1400–1482) was a true Renaissance innovator. He combined baked terracotta with painting by perfecting new modeling techniques and glaze recipes in one-of-a-kind, expressive, lustrous, long-lasting sculptures. From molds he customized the same compositions to meet the tastes and means of different patrons.

Giorgio Vasari, the famed Renaissance biographer, praised Luca for his uniquely Florentine art form that he deemed “almost eternal.” Della Robbia’s creations have certainly stood the test of time, with brilliance of color and luminous shine that endures some 500 years later.

“These sculptures are miracles,” said Alison Luchs, curator of early European sculpture and deputy head of the National Gallery of Art’s Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

Family and art blended seamlessly in the della Robbia workshop. Luca handed on his innovative sculpture glazing techniques to his nephew, Andrea della Robbia, who passed on the valued skills to his sons Giovanni, Girolamo and Luca the Younger.

Their craft was an act of faith itself, as the sculptor submits his modeled clay to the unpredictable kiln fire. And even as their distinct creations began to be admired widely and demand for them increased across Europe, the della Robbia modeling techniques and glaze recipes remained a closely guarded family secret, along with the family-owned clay bed near the Arno River.

No signatures are found on della Robbia creations because no other Renaissance artist succeeded in replicating their exclusive colors and sculptural forms. Noteworthy works by one competitor family, headed by Benedetto Buglioni, are included in the exhibit.

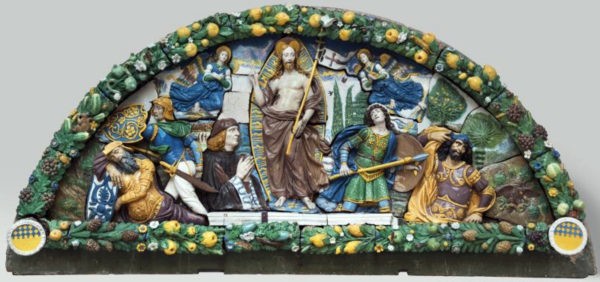

The Renaissance intersection of art and family continues into the present day in the monumental lunette titled “Resurrection of Christ.” In the early 16th century, a nobleman of the winemaking Antinori family commissioned Giovanni della Robbia to create a sculptural relief to decorate the garden gate at his family villa outside Florence.

Five hundred years later, that impressive masterpiece now welcomes visitors to the exhibit, with the current generation of the Antinori family providing generous support for its conservation and exhibition, through the Altria Group.

Composed of 46 pieces of glazed terracotta, fit together like a massive puzzle, the lunette shows the resurrected Christ in a mandorla of yellow and blue rays with attendant angels. An elaborate frame evokes the Tuscan countryside alive with green foliage and trees, golden fruit and flowers, and playful animals. Soldiers dressed in green, brown and gold fall back in fear while the Antinori patron kneels in fervent prayer before Christ. On the lower corners of the lunette are the Antinori family coat of arms.

Alessia Antinori, representing the family in its 26th generation, expressed their pride and delight in continuing the family’s historic connection to the Renaissance, first as patrons of Giovanni della Robbia’s original work, and now as supporters of this exhibit five centuries later.

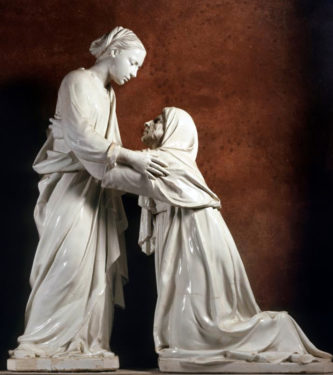

Another breathtaking piece is “The Visitation” (c. 1445). Here, the humble element of clay, shaped by Luca della Robbia’s hand, begins to speak. For as the youthful Mary and older Elizabeth, both pregnant, meet in tender embrace, one can almost hear these women sing a hymn of praise to God for the wonder of the Incarnation.

“Luca chooses white for simplicity,” and the “humility of clay radiates from this Gospel scene,” explained Marietta Cambareri, senior curator of European sculpture and the Jetskalina H. Phillips curator of Judaica at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. On loan from the Church of San Giovanni Fuorcivitas in the city of Pistoia, Italy, in the Diocese of Pistoia, “The Visitation” is one of six major loans from Italy, traveling to the U.S. for the first time. The exhibit’s two U.S. locations in Boston and Washington reflect the partnership of the Museum of Fine Arts with the National Gallery of Art.

Della Robbia sculptures decorated many spaces in Florence, from public squares and street corners, to cathedrals, chapels and altars, to private homes and domestic settings. This talented, hardworking family made art accessible to ordinary folk with Renaissance masterpieces that became part of everyday life. Wealthy patrons, like the Medici and Antinori families desired their timeless art. And so did individuals or families of humbler means who could only afford smaller devotional images for their homes.

Sullivan, author and educator, is a professor at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington and is the author of “The Beauty of Faith.”