By Nancy Weichec

SAN FRANCISCO (CNS) – To Andrew Galvan, Blessed Junipero Serra is a stalwart of faith and mission worthy of the title “saint.”

“He was all wood and nails. He was a tough dude. He fought, he defended, he wrangled, he was frustrated and he was frustrating,” Galvan told Catholic News Service.

A descendant of tribal members from the San Francisco Bay region, Galvan traces his family roots to California’s first Christians, thousands of whom were baptized and confirmed by the 18th-century Spanish missionary.

Pope Francis will canonize Blessed Junipero Sept. 23 in Washington. Galvan said he hopes to be there.

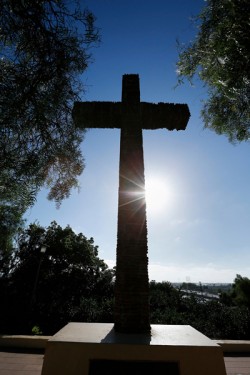

Long a promoter of Blessed Serra, Galvan is the museum director and curator of Old Mission Dolores, the sixth-oldest of California’s 21 historical missions.

He said Blessed Serra was “on fire” to heed Christ’s call to witness, like Jesus’ apostles and St. Francis of Assisi.

“His goal in life, from the time he was a novice … was to be a missionary to Indians in the Americas, to bring the Gospel message where it had never gone before.”

Galvan said the friar, who was beatified in 1988 by St. John Paul II, never veered from that objective and went about it tirelessly, foregoing any convenience for himself.

According to his biographers, he slept little, traveled thousands of miles by foot, quietly endured injury and pain, ate modestly and spent long hours in prayer. When Blessed Serra thought he was failing in his efforts to evangelize, he blamed such defeat on his own sins.

“My God, I couldn’t live the life he lived,” Galvan said.

Miquel Joseph Serra took the Franciscan habit at age 17. He chose the name Junipero, after a companion of St. Francis known for his holy simplicity.

Junipero Serra became an adept student of philosophy and theology and was inspired by the stories of saints and missionaries. Always looking outward, the friar left a successful and comfortable life as a professor to embark on a missionary journey to America, knowing he would never return to Spain.

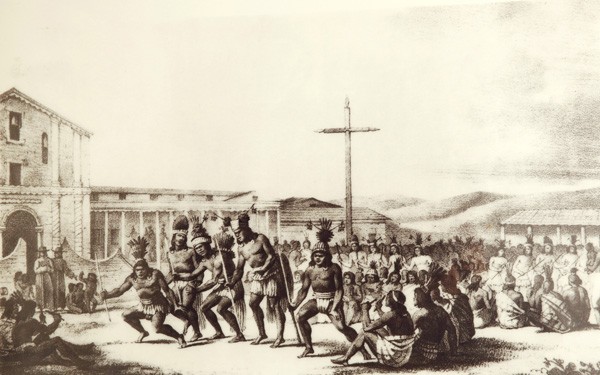

In Mexico, he spent 17 years building up Indian missions in the Sierra Gorda and traveling far and wide, preaching popular missions. In fervent sermons, he called on those who had fallen from faith to return to God’s mercy.

Blessed Junipero did not reach upper California until he was 55. And when he did, said Galvan, he jumped from his donkey and kissed the ground.

“He’s on sacred ground, because in his mind, being a student of (John Duns) Scotus, he is now entering this world that is completely innocent,” he said referring to the famed Franciscan priest-philosopher of the Middle Ages.

“And he (Serra) is the one bringing the Gospel where it has never been brought before.”

(story continues below)

Galvan has studied Blessed Serra for 37 years and has a unique connection to the soon-to-be saint. He can point directly to him as the person who brought Christ to his family.

“That’s a momentous event,” said Galvan. “I can go into Mission Dolores right here and say, ‘It is in this very room … that my family first became Christian.’ How many people have that joy and pleasure?”

Colonization’s Effect

Galvan, though, does not look back with rose-colored glasses. He is acutely aware of the toll upon the California native peoples by the missions, the colonial era and the times that followed.

He calls the encounter between Europeans and Indians an “unmitigated disaster.”

“The colonization destroyed the native people along the California coast because of the destruction of the native environment, the changing of lifestyle and the unfortunate introduction of European diseases.”

After Blessed Serra’s death in 1784, mission populations rose and then sharply dropped. Closely knit mission communities only worsened the spread of illness. Disease was rampant and deadly.

An interpretive sign in the graveyard of Old Mission Santa Barbara gives an idea of the loss: “More than 4,000 Chumash Indians are buried in this cemetery.”

Despite the harsh history, Galvan said Blessed Serra deserves his devotion.

“He loved my ancestors. He loved Indians, He was in love with the idea of being a missionary here. His descriptions of my ancestors are fantastic,” he said. “I’m in love with him and I’m devoted to him.”

Active Parishes

California mission history is so profound that it has been required study for all fourth-graders in the state. On mission field trips, students find museum displays, artwork and old artifacts, but also parishes that are very much alive.

“I think some people are surprised by that,” said Father Tom Elewaut, pastor of San Buenaventura Mission in Ventura.

Today, all but two of the 21 historical missions are active churches, and most of those are parishes that continue to serve local communities.

“We have 1,800 active parishioners that attend, participate in Sunday worship,” said Father Elewaut, adding that at every Mass there also are people visiting from across the U.S., Canada, Europe or other parts of the world.

People with ties to the California mission system see the canonization of its founder as a moment for reflection and reconciliation with native people.

“The canonization of (Blessed Junipero) Serra has really encouraged us, as well as the diocesan bishops, to seriously look at the place of the California mission Indians and our history and heritage,” said Franciscan Father Ken Laverone, co-postulator in Blessed Serra’s cause. He’s a California-born descendant of Spanish colonizers.

“It’s getting us to look at our relationships with the Native Americans and to reopen the doors of our mission in a greater sense.”