MIDDLE VILLAGE — Almost 2,800 years ago, the young King Ahaz, ruler of Judah, faced a brutal invasion — an event that seemingly had nothing to do with modern celebrations of Christ’s birth at Christmas.

Still, the 8th-century BC incident in the Syro-Ephraimite War yielded a declaration from the prophet Isaiah that resonates today during the Advent season.

Ahaz sought hope and reassurance during the attacks from the alliance of Syria and the Kingdom of Israel. They sought to pressure Ahaz to join them against Assyria, an aggressive Mesopotamian empire to the east.

So, the king turned to the prophet for a sign. At first, Isaiah didn’t want to test God, but then a message came to him — that a woman in his circle of influence would give birth to a son and “will call him Immanuel [God with us].”

One can question what the messiah’s arrival had to do with the problems of Ahaz (Isaiah 7:14) several centuries earlier.

The answer is that God communicates hope through Scripture, which he inspires for application in more than one situation, explained Father Nick Colalella, the parochial vicar for Our Lady of Hope in Middle Village.

Father Colalella, who also studied at the Pontifical Biblical Institute (the Biblicum) in Rome and has a background in Scripture, noted St. Augustine wrote that every Scripture is “literal” and “prophecy.”

Literal is what the author intended to convey to the original audience, given the circumstances. “Prophecy,” meanwhile, is a Scripture’s spiritual or prophetic meaning that transcends “above and beyond even what the author himself intended,” he added.

“That’s because God is really the author of Scripture, and it’s meant to fortify our faith,” Father Colalella explained. “The Old Testament is always looking toward and is interpreted through the Christ event.”

In the case of Ahaz, the prophecy came to pass — his troubles were sorted out when the alliance pressuring him to help fight Assyria was defeated, Father Colalella said. Thus, the literal interpretation was fulfilled.

But later, early Christians interpreted Isaiah’s prophecy to Ahaz as foretelling the birth of Jesus, referencing it in the New Testament. It and other prophecies are central to the observance of Advent — a time of waiting and preparation for the celebration of Christ’s birth at Christmas and his return at the Second Coming.

The promise is stated as early as Genesis 3:15 during God’s rebuke of the rebellious angel who posed as a serpent to deceive Adam and Eve: “And I will put enmity between you and the woman,” God said, “and between your offspring and hers; he will crush your head, and you will strike his heel.”

A couple hundred years after Isaiah, a new prophet, Jeremiah, made impassioned pleas for Judah to abandon its moral decay or risk the consequences of rejecting God. Unheeded, the prophecy came true. Jerusalem, the capital city, was sacked, and about 7,000 people were exiled into Babylonian captivity.

But the story didn’t end there. Speaking through Jeremiah, God said, “I will fulfill the promise I made to the house of Israel and the house of Judah. In those days, at that time, I will make a just shoot spring up for David; he shall do what is right and just in the land” (Jeremiah 33:14-15).

After about 70 years in captivity, the Babylonians were crushed by the Persians. The conquering king, Cyrus, allowed the exiled and their offspring to their home, Jerusalem. This act, Father Colalella noted, was prophesied by Isaiah (Isaiah 40:1-48:22).

Again, the early Christians interpreted it as a foretelling of the Second Coming.

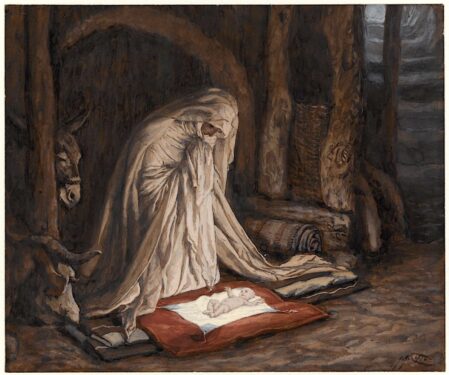

The aforementioned “just shoot” springing from the bloodline of King David is, of course, a baby born of a virgin — the same hope and joy of people today — Jesus.

The origins of the season of Advent are unclear, although scholars agree it existed by 480 A.D.

The beginning of each Advent season includes readings about the second coming, with the stories of the Annunciation and the birth highlighted towards the end. It is an invitation to accept the hope assured by God by sending his son, incarnate, as stated in Scripture, especially the Old Testament prophecies, Father Colalella said.

He said Advent — meaning “a coming” and, in this case, Christ — has three forms, as defined by St. Bernard Clairvaux (1090-1153) — Christ has come, Christ will come, and Christ in his mystical body, the Church, is already here.

“And,” Father Colalella concluded, “these are little guarantees, that what Christ says is true — that we can trust in his word, that ‘I will come again in glory, and I will be with you until the end of the age.’ ”