PROSPECT HEIGHTS — Catholicism has been present in the United States since before its formation, due to French and Spanish colonization. In the British Colonies that would serve as the first 13 states, however, their presence was less prominent and welcomed.

In fact, there was not a Catholic Church in New York City until two years after the American Revolution ended. However, remnants of the impact of devout Catholics during the Colonial Era, and the founding of the country, can be seen in history books and in person throughout the city, thanks to their roles during the American Revolution.

Many Catholics sided with the Patriots during the Revolution, and because of the alliance with France, a predominantly Catholic country, anti-Catholicism was toned down during the war.

General George Washington forbade his soldiers to celebrate Guy Fawkes Day, an English holiday that involved the burning of an effigy of the pope, and St. Patrick’s Day was celebrated on his orders.

As written in the Order in Quarters issued by General Washington, November 5, 1775: “As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope. He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture.”

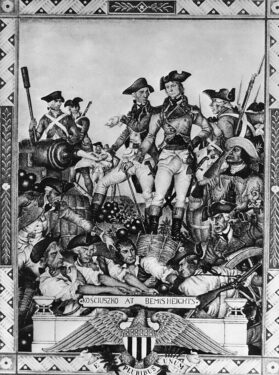

Captain John Barry of the Navy and Stephen Moylan of the Continental Army, two well-known Catholic soldiers during the war, won distinction for their bravery and impact on the Colonial victory over the British. Less known is Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko, a Polish soldier posted at Fort Ticonderoga under the assignment of Major General Horatio Gates. The Kosciuszko Bridge in New York is named after him.

After the war, Kosciuszko used the money he received to free enslaved people. For this, he should get more credit, says Queens resident Marvin Jeffcoat, who serves as the National 3rd Vice Commander of Catholic War Veterans of the USA. In his eyes, Kosciuszko continued to fight for the freedom of all after the War for Independence.

“I thought that was very admirable at a time when slavery was considered OK, and people tried to justify it by misquoting various Bible verses,” Jeffcoat said. “It showed that he was a principled man.”

Only one of the original 13 colonies expressly offered safe haven for Catholics: Maryland, which was founded in large part for those who had faced persecution in England to be able to practice their faith freely.

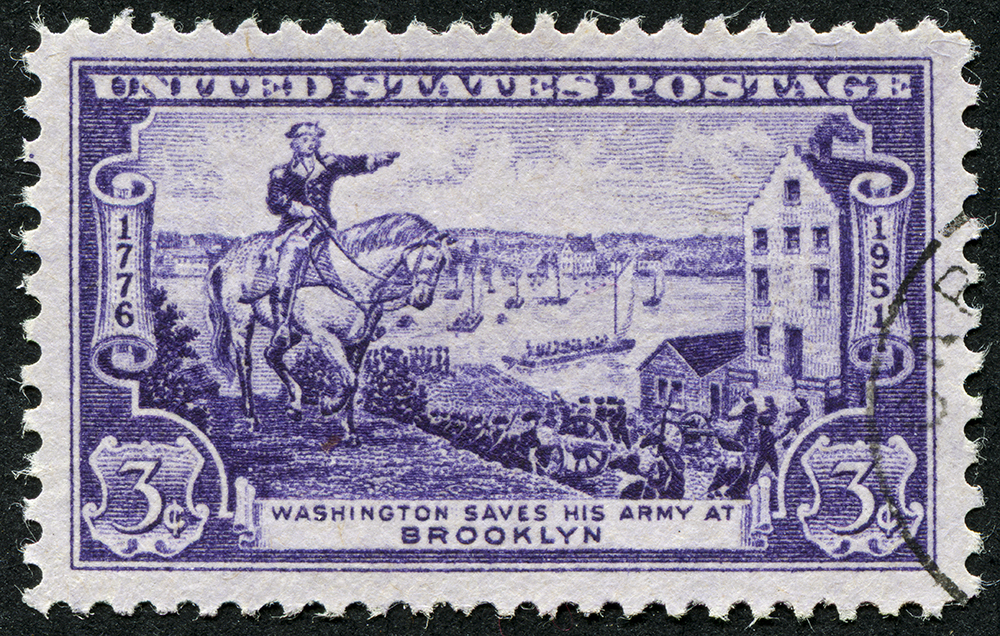

It was thanks to the bravery of a Catholic regiment from Maryland that the Revolutionary War did not end in 1776. After the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the British massed an army of more than 32,000 soldiers, seeking to end the war at what is now known as the Battle of Brooklyn, or the Battle of Long Island.

During the Battle of Brooklyn, Governor Charles Carroll — for whom the neighborhood Carroll Gardens is named — led a small group of the 1st Maryland Regiment into battle. They would come to be known as the Maryland 400, or “Marylanders.”

This year’s reenactment is set for Sunday, August 25, starting at 11 a.m. For more information on the free event, visit www.green-wood.com/

The regiment lost their lives during the battle, falling near the site of the Old Stone House, in what is now Brooklyn’s Park Slope, according to the New York Times. The distraction they caused gave General Washington and the Colonial army the time they needed to retreat to Brooklyn Heights, and from there they made it out of New York City. While they lost the battle on August 27, 1776, the army lived to fight another day.

Carroll also made history as the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence. Because of his involvement, Maryland lifted the ban on Catholics holding public office, and Carroll later represented the state of Maryland in Congress.

“I definitely think the tenets of our faith played not only an integral part in the Declaration of Independence but also in the framing of the Constitution because our system of governance has values all based on Judeo-Christian values. I think that gets lost today,” Jeffcoat said.

One of the oldest commemorations to the Catholic impact in the Revolutionary War is in lower Manhattan’s Battery Park, which recognizes a Daughter of the Revolution who has since been given the highest honor in Catholicism. St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, a convert to the faith, grew up in New York City during the American Revolution, and lived during the British occupation of the city. She established the first free Catholic school for girls in the country as well as the Sisters of Charity order, and in 1975, she was the first American-born saint to be canonized.

Her shrine can be found at the St. Peter Church, the oldest Catholic Church in New York City. A center for the faith during American Colonialism, St. Peter Church was founded in 1785, two years before the establishment of the United States government, and is the origin of the Archdiocese of New York.

“Elizabeth Ann Seton is a saint. St Elizabeth Ann Seton is an American. All of us say this with special joy, and with the intention of honoring the land and the nation from which she sprang forth as the first flower in the calendar of the saints,” Pope Paul VI said at her canonization in 1975.