NEW LOTS — A lawsuit alleging that New York City’s property tax system unfairly burdens low-income residents was dismissed by a high court a few years ago, but it now has new life.

Tax Equity Now New York, or TENNY, brought the suit in 2017 against the city and the state, claiming NYC’s property tax system is inequitable, opaque, and forces some people to pay an uneven share of the state’s tax revenues.

TENNY also alleged that this system fuels the ongoing housing crisis and perpetuates segregation.

The lawsuit advanced through the court system until the state’s Appellate Division dismissed it in 2020 because the city’s tax system was legal, and concluded it was up to the Legislature to make changes.

Three months ago, however, the State Court of Appeals, the highest non-federal bench in New York, overturned the dismissal from 2020. This 4-3 decision on March 19 thus allowed the suit to go back to State Supreme Court in Manhattan.

This property tax crisis, however, has been brewing since the early 1980s. Politicians have tried to correct it, but legislation never prevailed. Now, the city’s largest source of revenue comes from property taxes — about $35 billion each year.

Enter TENNY, a coalition of property owners, renters, and other advocacy groups.

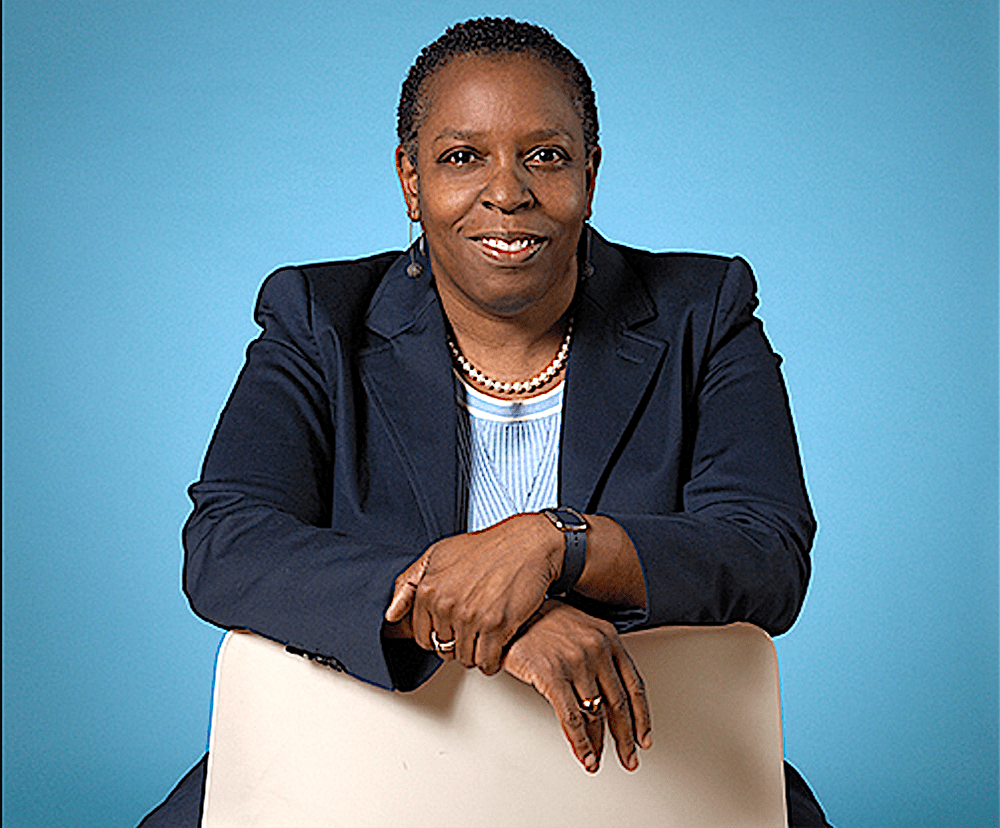

Under the leadership of TENNY policy director Martha Stark, the group worked to illuminate the complicated factors that shift a disproportionate tax burden onto low-income property owners.

The Legislature in 1981 approved New York City’s current property rate system, with built-in caps on the assessed value of homes that appreciate. TENNY has long asserted that, yes, owners of these properties are still taxed, but not on the full values of their property.

Stark could not be reached to comment for this article. However, she previously explained to The Tablet why the Legislature created the caps.

The idea, she said, was to protect homeowners from drastic spikes in property values to keep assessments from growing more than 6% every year, and no more than 20% over five years.

But, she added, owners of homes that don’t appreciate more than 6% don’t get a cap and must pay taxes on the full assessed value of their homes.

For example, the lawsuit describes a property in Canarsie that is assessed at “triple the rate of the same properties in Park Slope.”

Also, the lawsuit claimed that the city taxes the owners of rental buildings at higher rates than owners of luxury condominiums and co-ops. Consequently, tenants are also charged higher rents, according to the lawsuit.

The Appellate Division concluded that the caps do not cause discrimination because they relate to the city’s efforts to promote home ownership. The caps also helped homeowners with rapidly appreciating properties from facing rapid tax increases.

Father Ed Mason, pastor of Mary, Mother of the Church in New Lots, is a longtime advocate for affordable housing in Brooklyn. He applauded the lawsuit’s revival, but also noted the legal battle is far from won. He said many people hoping for tax relief can’t wait any longer.

Father Mason said that, as housing becomes increasingly unaffordable, people become poorer, so they leave the city.

This also leaves fewer people to contribute to the local economy, but also reduces the populations of public schools and even parishes. Fewer occupied school desks and church pews spells less money to support them.

“People are breaking their backs and sacrificing other quality-of-life issues to be able to afford their rent,” Father Mason said. “But there is no affordable housing — period.”

Meanwhile, parishioners who stay have little to sustain them, except for their faith.

“For some, that’s the only stable thing in their lives,” Father Mason said.